Winter seems like a good time to take a break from farming and travel somewhere warm and relaxing. Instead, I vacationed in snowy Vermont, taking time to help my parents, now in their early 80’s, prepare to sell the house they have lived in for over 50 years. Last year they decided it was time to move closer to my sister in a different part of the state. Soon after, my mom fell and broke her hip and the plan to sell the house progressed slowly while her physical ability declined steadily.

Winter seems like a good time to take a break from farming and travel somewhere warm and relaxing. Instead, I vacationed in snowy Vermont, taking time to help my parents, now in their early 80’s, prepare to sell the house they have lived in for over 50 years. Last year they decided it was time to move closer to my sister in a different part of the state. Soon after, my mom fell and broke her hip and the plan to sell the house progressed slowly while her physical ability declined steadily.

The house portrays a timeline of their lives—relics such as furniture from their first apartment in New York as newlyweds, to the remnants of a handmade cloth doll empire my mother amassed in that place. Over the years many of the rooms alternated as her workshop and retail space. Not to mention some of the remnants of their three children. With such an epic accumulation of stuff animated with memories, where does one begin?

My mom struggles to let go of a needlepoint chair; it was a wedding gift from funds pooled by the Jesuit priests at Colombia University during her first secretarial job. Despite the now tattered needlepoint, it holds the love of all those priests she looked after administratively and otherwise. Mapping out the layout of a much smaller future living area, she relinquishes the grip on the chair. It can go.

In fifty years, very little has changed about the house, save the decline of all of its contents, now including my parents. I imagine that the crumbling ceiling plaster, the dated, peeling wallpaper, the still connected knob and tube electrical wiring will be unattractive to a potential buyer, but their real estate agent seems upbeat, even in the depths of the basement. The stone foundation is still as strong as when it was built in 1844 with no observable cracks or leaks and the furnace and plumbing upgrades are still in good shape. However, the extensive contents must be addressed and the clutter hauled off. This is easier said than done, for my parents, and for me.

Last summer I was going through boxes with some high school friends who were helping us take a load to the dump, when our eyes were drawn to the familiar bright colors of a Strawberry Shortcake twin sheet and a Peanuts pillowcase. Charlie Brown’s conversation bubble exclaimed “Happiness is being one of the gang.” I remember the comfort of these things as I drifted off to sleep as a child, but was willing to let them go. When I arrived back home a week later, I was greeted by a package of the freshly washed and de-stained sheets, with a note from my friend saying she couldn’t help but resurrect them! When my sister stays in the vintage guest trailer on our farm, she feels right at home.

I started meditating ten years ago when my marriage dissolved. Impermanence is the cornerstone of Buddhist teachings, and accepting that change is a constant comforted me during this chaotic time. On a visit home, I noticed the Buddha statue my dad brought back from Japan while in the U.S. Navy in the early 1960’s. The Buddha sat in lotus pose on a shelf in our family room, silently emanating loving kindness. Dad insisted I take the Buddha with me, a fatherly offering that touched me. Ironically, at the time I was liberating myself from many possessions. The statue accompanied me through several moves over the next few years; from a farm yurt in Santa Cruz to the homestead where I now live in Rimrock. The same Buddha my dad was drawn to all those years ago now sits in my living room where I share silence with my partner, Mike.

After leaving his father’s palace and all his worldly possessions behind to seek the truth of existence, the Buddha came to the realization that “Attachment is the root of suffering.” The things we cling to are layered with stories, meaning and emotions. Can we find freedom when we let them go?

During a particularly intense debate about the fate of a dining room table this past week, I read my parents one of my favorite poems by Mary Oliver. Her answer to the problem of a storage unit:

“As I grew older the things I cared

about grew fewer, but were more

important. So one day I undid the lock

and called the trash man. He took everything.

I felt like the little donkey when

his burden is finally lifted. Things!

Burn them, burn them! Make a beautiful

fire! More room in your heart for love,

for the trees! For the birds who own

nothing—the reason they can fly.”

~ excerpt from the poem “Storage”

We cannot take things, not even our memories, with us when we leave this earthly plane. What really matters is the present moment we are sharing.

In the attic, I find boxes of my mom’s journals filled with her to-lists, ideas, drawings, inspiration and poetry. There is an entire room full of calico fabric, ribbon and rickrack from fifty years of making dolls. These creative trappings have been the hardest for her let go of. Through the years, the dolls she made have found homes and been passed to multiple generations as unique expressions of love. In keeping with this legacy, we decide to offer the calico fabric to a group that makes quilts for those in need.

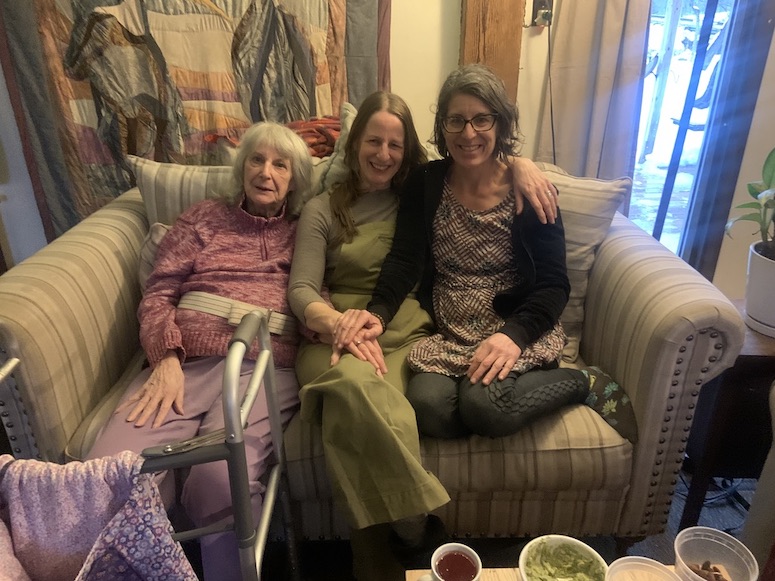

In her prime, my mom was a sturdy, creative powerhouse who could command a room with her presence. She was in constant motion. Although she is more sedentary and shrinking in size and volume, my mother still possesses her hearty belly laugh. She appears more bony and birdlike each time I see her, as if a stiff breeze could blow her over. With the lightening of her load, I wonder if she might just start soaring.

Moving, growing old, change— is an emotional rollercoaster, and a radical opportunity to examine what truly matters. My sister and I enjoy heartfelt conversations as we cook nourishing meals together for our parents and her family. The true meat of our lives resides in these moments of connection, in my dad’s stories, that become more colorful and detailed as he ages. His hearing is fading but the insights from a long life are flowing freely. We enjoy tea together into the evening around the wood stove and the comfort of each other’s company for the time being.