As we enter the darker side of the year, the veil between the earth and spirit realm is a gossamer curtain. As the leaves fall and the days grow shorter, I sense the transience of each moment. It is time to say goodbye to the garden and I grieve the loss of all of my flowers. A few marigolds are still blooming, and I leave them for the bees and butterflies who may be visiting ancestors.

As we enter the darker side of the year, the veil between the earth and spirit realm is a gossamer curtain. As the leaves fall and the days grow shorter, I sense the transience of each moment. It is time to say goodbye to the garden and I grieve the loss of all of my flowers. A few marigolds are still blooming, and I leave them for the bees and butterflies who may be visiting ancestors.

Many details about my ancestors and those who lived on this land are not known. Both my maternal and paternal grandmothers descended from Ireland and Scotland, died before I could be imprinted with their foods and gardens, their smells, or the sound of their voices. On this farm, I have found pottery bits dating back 1000 years, a brick storage box nestled in the limestone cliff and a remnant pear tree that is almost 100 years old. For the recent Samhain or Day of the Dead celebration, I called in my ancestors and those who tended this land. I built an altar and placed photographs of my grandmothers and lit candles to let them know I am thinking of them.

This year I am mourning the loss of one of our giant Arizona ash trees — nearly a century old — which felt like losing a relative. Once some time back, the main trunk was topped, and rot crept into the heartwood, extending throughout its core to the roots. The tree leaned over the high tunnel growing area, composting toilet and two sheds. An arborist deemed it a “hazard tree,” and I struggled for several months with the decision to remove it. It took a crew of arborists and tree workers an entire day, several chainsaws and a crane to safely take it down. Not to mention a big chunk of my savings.

Now, when scanning the farm horizon, my eyes rest on this exposed spot, like a missing tooth. However, this tree’s spirit lives on. The rotted slab is the foundation of the altar, another solid section was milled and is curing for a future table. The canopy is a heaping pile of wood chips for shading garden paths. There is a steady supply of firewood and a circle of giant stumps for gathering around the fire.

At 3,500 feet elevation in the desert, it is extraordinary to live beneath this extensive canopy of shade. Farming in the carbon-rich understory my plants are protected by the underground communion between roots, microbes and fungi. The soil sings with the rich organic matter and diversity of living beings transporting water, nutrients and signals through these root systems.

Arizona ash (Fraxinus velutina) are native to the American southwest often growing near a permanent underground water supply. Guidebooks record them extending to heights of 40 feet and living for 50 years. Yet the trees on the farm have a strong presence. They form a protective, magical grove along a limestone cliff reaching nearly 100 feet tall, arching into the desert just beyond.

Arizona ash (Fraxinus velutina) are native to the American southwest often growing near a permanent underground water supply. Guidebooks record them extending to heights of 40 feet and living for 50 years. Yet the trees on the farm have a strong presence. They form a protective, magical grove along a limestone cliff reaching nearly 100 feet tall, arching into the desert just beyond.

At work on the farm, it is easy to be swept into the micro-tasks — a dozen flower crowns for an upcoming wedding, the cool season flower seeds and bulbs that need to be planted, and gardens to be put to bed for the season. The imposing yet benevolent statues of these trees literally shake me back into the present moment, garnering my attention with the delicate sound of leaves raining down with the slightest gust of wind.

This fall, I spent several Sunday afternoons lying beneath the blazing yellow-orange leaf canopy, which seemed to be shimmering with light inside and out. What was once a mass of dense green shade was drained of life. I marveled at the effortlessness with which the trees released the energy of everything they had grown this season. Leaves sailed down from the tops of the ash canopy with giddy abandon against an impossibly blue sky. Each leaf met its inevitable moment with the ground as if dancing to silent music. Some flew off as if on a mission, others meandered down as if skipping through the sky. A few tumbled clumsily and others spun and twirled like pinwheels. I became giddy with the freedom and levity of being covered in leaves. I felt wealthy surrounded by all this gold laying on the ground. I remembered a line from the Mary Oliver poem, “Song for Autumn”:

“In the deep fall

don’t you imagine the leaves think how

comfortable it will be to touch

the earth instead of the

nothingness of air and the endless

freshets of wind?”

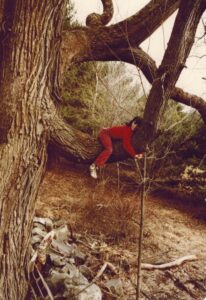

Growing up in rural Vermont the forests were dark with tree canopies. From an early age, I sought refuge amongst them. Even then I was communing with my ancestors unconsciously, allowing myself to be guided by the ways of plants and trees and forests. I wandered the thick, mossy groves of Mount Flamstead behind our house experiencing the subtle seasonal changes and a now-familiar ache in my heart at the sight of flaming autumn leaves against blue sky. I loved climbing them and dreamed of building my own treehouse, making several attempts. The trees on my farm bring me back to my little tomboy self and to the wonder I experienced. I remember how the trees comforted me as a child. The woods soothed and guided me, they awakened my heart to beauty and my mind to curiosity. I remember feeling that the earth loved me wholeheartedly.

With the trees on the farm, I feel the same tenderness, as if I am sheltered, held, and protected in the earth’s wisdom and embrace. My ancestors and those who lived on this land were intimate with the earth’s cycles and when I am quiet they whisper to me through the trees. “We are not separate. We are nature.”