This week’s guest columnist is Karla Theilen

This week’s guest columnist is Karla Theilen

“All I need to kick this virus once and for all is lots of hot tea, some lemonade and a clean pair of underwear,” my patient announced as I fastened the blood pressure cuff around her arm. She paused and stared straight ahead, then her head flew back to release a laugh that sounded like the descending trill of a canyon wren. I burst into laughter, too, even though I knew she couldn’t hear me through the two layers of masks, or over the constant humming of the negative air pressure machine. I’ve decided this is what the lines around my eyes are for; to let people know when I am happy.

When the cuff is done squeezing, I peel the Velcro apart to release her arm and, still giggling to herself, she points her chin in the direction of bed three and says, “Also, her phone is dead.”

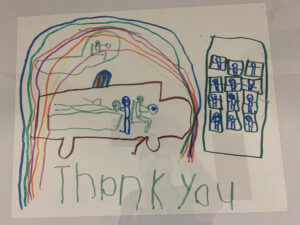

Room 27, or “the four-bed room” as we call it, or sometimes “the ladies’ room,” has four beds in it, and all feet point to the middle. Once upon a time rooms like this were the norm. They were called wards. Maybe they still are. I love this kind of nursing best, nursing in community. It reminds me of a past life I wish I’d had as a nurse in a TB ward somewhere in the Adirondacks, rolling patients in wicker wheelchairs out onto sunny verandas with quilts over their knees, playing cards, singing and putting on plays with them. Essentially, my dream job.

There is some tattling that goes on in Room 27, but it is usually helpful. That one has not been doing her breathing machine, this one wants hot tea, that one needs to use the bathroom. Sometimes I hear words of encouragement exchanged, or at least that is what I pick up from the tone. The women in Room 27 speak mostly Navajo to one another, and I stand in awe at their adroit language skills as I lurk shamefully and shrink back into the six or seven words of my Navajo vocabulary. Going back and forth between their native tongue and English, doing the hard work of translating thoughts into words just in order to help the nurse help them.

I leave the room and go dig through the drawer in the filing cabinet at the nurse’s station where abandoned phone chargers usually land. There is only one, and it is wrapped in a thick hot pink rubber band with a staff member’s name on it and the words, DO NOT TOUCH!

The ubiquity of cell phone chargers everywhere but here seems absurd in this moment. Drug stores, dollar stores and truck stops have them in every length, every color of the rainbow. All I need right now is one.

Once we got through the height of the COVID surge and moved into the territory of patients getting better, it became evident that the link between recovering patients and the rest of their lives was a cell phone charger. Hardly anyone arrives sick on the unit with one, and with visitation prohibited, the process for families to get a charger to their loved one is, well, a process. A phone charger is not what you think of on the way to the Emergency Room. EMTs don’t usually ask, “Now, do you have your phone charger?” as they load the gurney onto the ambulance. Any one of us might launch into a cardiac arrhythmia just thinking about three weeks in a hospital bed without a charged phone.

In Room 27, the patients have to share a bathroom, they have to share the window, they have to share a nurse. They have to be sick in front of one another, they have to have to struggle in front of one another, they have to be scared and lonely with an audience.

The women in Room 27 also share their phone chargers apparently, because when I come back to the room empty handed, Bed 3’s phone is connected to an outlet by a long black cord. Nobody says where it came from, but the one with the laugh like a bird song says, “I guess today is just a good day.”

And it is. But there have been bad days in Room 27, just like in all the other rooms. On one of the worst days, the four beds contained a total of two very sick patients, one on the edge, and one on the mend. That day, I instructed the patient I had deemed to be the least sick and most reliable to call me if anyone needed anything. It was hard to hear the beeping through the closed door, and the light above the door to Room 27 is somehow stuck in the on position. At first this leads nurses to believe there is always something needed in 27, but soon it fades out, like white noise.

It was a ruthlessly busy day, and while I put out fires all around me, I worried about the patient in 27 that I’d left with the call button. There was no telling how softly or hard this responsibility may have fallen on her. I wondered if this was how people feel leaving their oldest child in charge, and wondered more about what it feels like to be the oldest child. We’re all in this together. The phrase almost feels commodified these days, like people walking around with T-shirts that say “Breathe.” But in Room 27, breathing is the work of the day, and being in it together is not just a hashtag.

When I came to Tuba City to work at the hospital back in April, there were more bad days than good days. But it is June now, and we are tipping the balance into better days. Good days even. We send recovered patients home daily, back into the land of the living. We send them through a hallway lined with smiling, clapping, cheering staff. We send them home with masks, with goodie bags and pens that say “I Survived!” And before they leave, we charge their phones to 100 percent.

Karla Theilen is an RN who splits time between Arizona and Montana, filling her scrub pockets with notes, writing down things that she does not want to forget on alcohol swab packets. She has been Facebook-free since 1972.