My brother called last night just as I’d climbed under my covers. We traded stories about emotional numbness and our lapsed personal hygiene. I’ve spent the whole day wearing nothing but my underpants, he said. I countered with the admission that I hadn’t showered in five days.

My brother called last night just as I’d climbed under my covers. We traded stories about emotional numbness and our lapsed personal hygiene. I’ve spent the whole day wearing nothing but my underpants, he said. I countered with the admission that I hadn’t showered in five days.

He told me that my nephew—his 25-year-old son living and working in New York City—has a new girlfriend. They’d all shared a Zoom dinner last night. My nephew and his new sweetie cooked pasta in Brooklyn; my brother and sis-in-law cooked pasta in Miami. How is she? I asked. The new girlfriend.

I dunno, my brother said. She was a tiny face on a tiny screen.

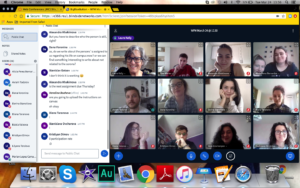

And this, it seems, neatly encapsulates pandemic togetherness. Tiny faces, tiny screens.

I teach media writing and storytelling. Before the pandemic, I was an action film. Now, I am a Cubist painting. Like millions of others around the world, I am now a teacher who talks into a machine. I look at a checkerboard of tiny faces and say what it is I have to say. It gives me vertigo as I undergo this disruption of my identity.

After class I twitch with feelings of incompleteness and inadequacy. Not in regard to mastering the technology, but for my disrupted participation in the nourishing, physical space of university. In our university we are a small, enmeshed community of learners and thinkers. Students live on campus; it is there that they meet the world and discuss it deeply. Through this, they engage in the messy ongoing process of creating themselves, and so do I. We participate in what Professor Gert Biesta calls “the beautiful risk of education.”

It’s a Monday, and I have class at 4 p.m. I sit in my kitchen wearing yoga pants. I’m barefoot. Half a sandwich sits in my lap. I talk into a silver portal and speak to my own face. Inside my head I am distracted by the places where my hair sticks out and self-conscious about my propensity to gesture like an opera diva even, it seems, when I am the only person in the room. Is there learning happening online? Almost certainly, but I have not yet recalibrated my meters.

Mostly classes feel like being together in the dark. The public chat space is where my students want to communicate but for discussion we need to talk out loud. They unmute their mics and their voices come from nowhere, startling me with their potency. I don’t want their tiny faces; I need the intimacy of their disembodied voices for any of what I am doing to make sense.

I find some comfort knowing I am one of millions of teachers unfastened from the familiar architecture of our daily lives and rewriting ourselves as educators. I’ve been reflecting deeply on what my work means. What I mean to the work. I read about the Maori word ako, a concept that does not ask for the teacher to know everything. Instead the value is put on reciprocal relationships. Teachers create settings where everyone brings knowledge with them and shares it like a big potluck dinner.

I read more from Biesta, a theorist and professor who is measured and philosophical in his approach to education. He calls it a practice, a slow practice that is “difficult, insecure, unpredictable, and full of risks and uncertainties.” I think he is describing the world as it is now. Maybe the world as it always is.

Last night I slept 11 hours. I dreamed I was in outer space in a white, puffy suit. I was tied by what looked like a jump rope to a space ship I’ve probably seen on Star Trek. My arms and legs were outstretched and dangling, as if I were floating in a swimming pool. My space helmet was shaped like a globe. I wasn’t afraid or scared; I had no feelings. Or maybe I had so many feelings that they made a Jackson Pollack jumble inside me.

I miss the classroom. I miss the buzz and flow of campus. I miss my students and their shoes and haircuts and fingernails and water bottles. How can I transcend my missing? How can I acknowledge these strange times and use them to dive more deeply into myself? How can I submit, as I ask my students to do, to this difficulty, this risk, this uncertainty?

Maybe slowly and together, just as it seems we are all doing, day by day.