There are a few things that make me think of my grandfather.

There are a few things that make me think of my grandfather.

I think of him when I hear Johnny Cash sing about God and death. I think of him when the sunset casts the West in an orange glow.

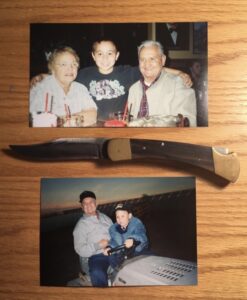

I think of him when I hold his old Buck knife in my hands, turning it over and over, opening and closing the blade, balancing it on my fingertips. I think of him when I’m sitting in my car as a freight train comes rolling down the tracks. Recently, I came across the story of the abandoned town of Centralia, Pennsylvania. In the 60s, a botched effort to clean up the town’s landfill by setting it on fire caused the blaze to spread to the maze of mineshafts underneath the town, where it’s still burning to this day. For some reason, I found the story of the Centralia Mine Fire a comforting reminder of how some things find the strength to thrive and endure. For some reason, when I became captivated by the story and its demonstration of nature’s resilience, I also found myself thinking of my grandfather.

The quaint little trailer in Chino Valley that my grandparents called home holds some of the best memories of my childhood. Family conversation in the living room, ice cream and game shows after dinner, watching Grandma complete a gargantuan 1000-piece puzzle, playing with Grandpa’s stash of toy cars and board games—these are moments I look back on fondly, but the best memories I have are of playing outside. Grandpa wouldn’t let his cane impede him when he went outside to play with his grandsons. His property seemed huge to me as a child, but he usually found the energy to follow us on whatever foolhardy crusade our wild imaginations had conjured that day. Otherwise, we could find him in his garage tinkering with tools, fixing an old CB radio or some other ancient thing he’d picked up from a yard sale. If I couldn’t tempt him for target practice with his BB gun or rides around on his “tractor” (his riding lawnmower which I consider to be my warmup to driver’s ed), we’d spend our time playing around with a remote-control toy. One day, when I was young enough to still make dumb choices but old enough to know better, I had the brilliant idea to fly his brand-new helicopter toy into a big tree in the yard. The plastic rotors shattered into a million pieces and sent the poor aircraft tumbling down to earth like Icarus himself. Grandpa was understandably angry with me for a few minutes, but it didn’t seem to last. My brother and I had gotten some enjoyment out of it, even for a brief time, and I think what mattered most to him was seeing his grandsons happy.

Grandpa became sick in my early twenties—a quick and vicious battle with cancer that left him confined to a hospice bed in the living from for the last few months of his life. Things had taken a turn for the worse just before we made plans to visit for the first—and for all we knew, possibly the last—time. He slept for most of the day, so our time was spent with Grandma as she filled us in on how he’d been doing. When he was awake, his voice was ragged and weak and he choked on the few words he could get out. A portable toilet had been moved into the living room, and I helped him out of bed to use it. He felt frail in my arms. It seemed like any small movements I made caused him to groan in pain. My family fired a few heated and conflicting directions at me as I struggled to help him, but I finally managed to set him down. Then I ran into the kitchen and cried alone. A couple hours later, we all said our goodbyes to him one by one. I held his hand in mine as he mustered enough energy to tell me not to cry, to tell me he loved me. As our car rolled down their dirt driveway, I thought I would never see him again.

I’ve often heard about cancer patients getting a “second wind” shortly before they pass away, and I’m glad I got to see Grandpa’s. The very last time I saw him, he was alert, upright, talking, and smiling like his old self, almost as if he still had some spark of life left. I don’t have many specific memories of that day, probably because it seemed like any other visit before he got sick. I’m grateful I had one last good day with him.

My brother came home to visit recently, and the two of us took a drive to see Grandma at her retirement community. After an hour or so of catching up (she had completed yet another puzzle and was going to hang it in her window to show it off to the other residents), we took a drive up to Chino Valley Cemetery to pay Grandpa a visit. It’s a small, unassuming place, surrounded by ranches and open fields, and on that particular day, the wind was sending huge billowing clouds rolling across the blue sky. It’s the kind of place I’d imagine Grandpa would be happy to rest. His plot is a rectangular patch of grass with a red brick border. A black and gold-accented plaque at the head bears his name and dates of birth and death, no special epitaphs or quotations, a simple plaque to memorialize a simple man. Grandma gestured with her cane at the large space of grass beneath the plaque, joking that when it’s her time to go, she’ll get a big plaque that takes up the rest of the plot. She had us clean out some rocks and twigs that had found their way onto the grass. We said hello and I cried for a bit. On the drive back home, my brother and I remarked how strikingly different the area looked compared to what we were used to seeing. Weeks of rainfall across northern Arizona had totally changed the landscape. We remembered it generally being a dry and brown prairie environment, but now, we saw bunches of flowers amidst seas of vibrant and brilliantly green grass. It had never seemed this beautiful and alive before. Again, I found myself thinking of Grandpa.

Shortly after that visit is when I stumbled across the story of Centralia, Pennsylvania, a ghost town and niche tourist destination. In the 60s, the town landfill was set on fire by the residents after long deliberation about the best method to clean it up. The landfill was built on an old strip mine and the fire began to spread uncontrollably through the old underground mineshafts. Eventually, the fire spread to the town’s operating coal mine, resulting in the mine’s evacuation and closure. Subsequent efforts to contain the fire failed over the years, being deemed too costly or complicated. The town quickly followed suit and the citizens were relocated in the mid-80s. Currently, only five residents remain in Centralia, their properties waiting to be seized through eminent domain after their deaths. In some places, smoke from the fire has pushed up through the earth and broken through the asphalt, letting the world know that it’s still there and still burning. Photos show the town’s remaining buildings and streets covered with graffiti from tourists, proclaiming “burn, baby, burn!” The fire is estimated to keep burning underground for another 250 years.

I can’t quite put my finger on why, but I thought of my grandfather when I heard about this little town in Pennsylvania with a blazing inferno underneath it. Maybe it brings me peace hoping that a little piece of him that has kept burning even now that he’s gone. These days, I often find myself anxiously thinking of the future. I wonder what this world will look like in the next few decades of my lifetime, not to mention the next two and a half centuries. I find myself worrying as my generation faces the growing problems of climate change and financial inequality. I find myself worrying more and more for my friends and family. I find myself considering how far I’ve come in my own struggles with mental health, and also how far I still have to go. I don’t know if there is an afterlife or such a thing as a soul, but after I die, I hope my soul finds its way into that fire burning underneath Centralia, Pennsylvania. I’d like to be part of something alive, raging, and seemingly eternal.