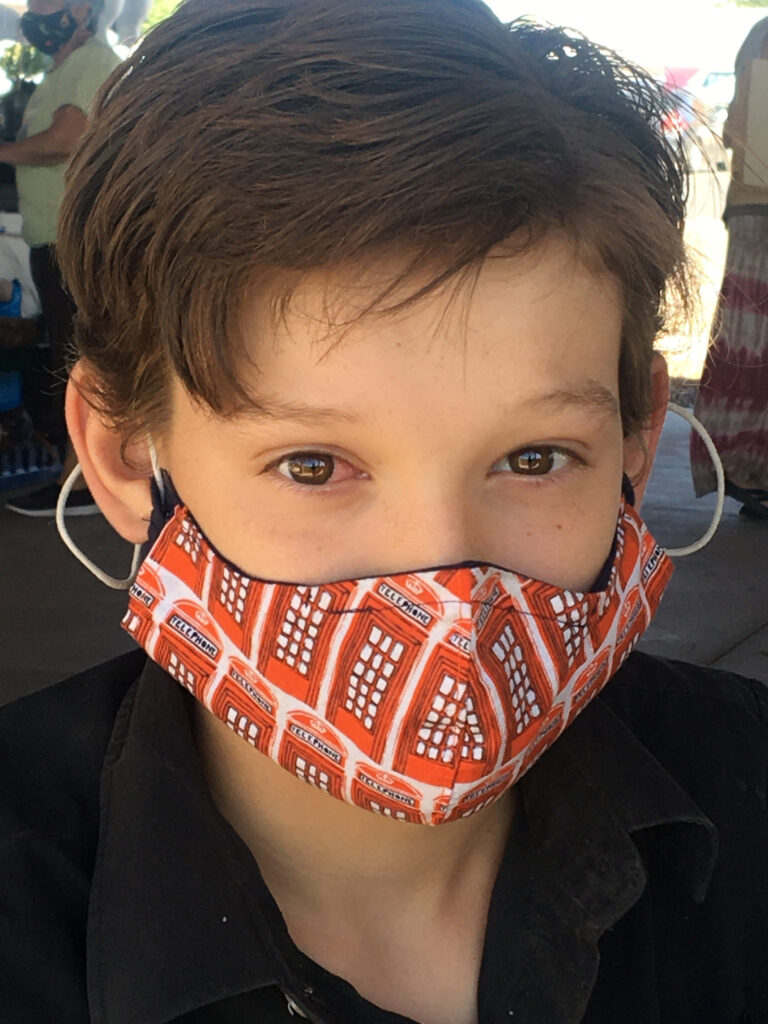

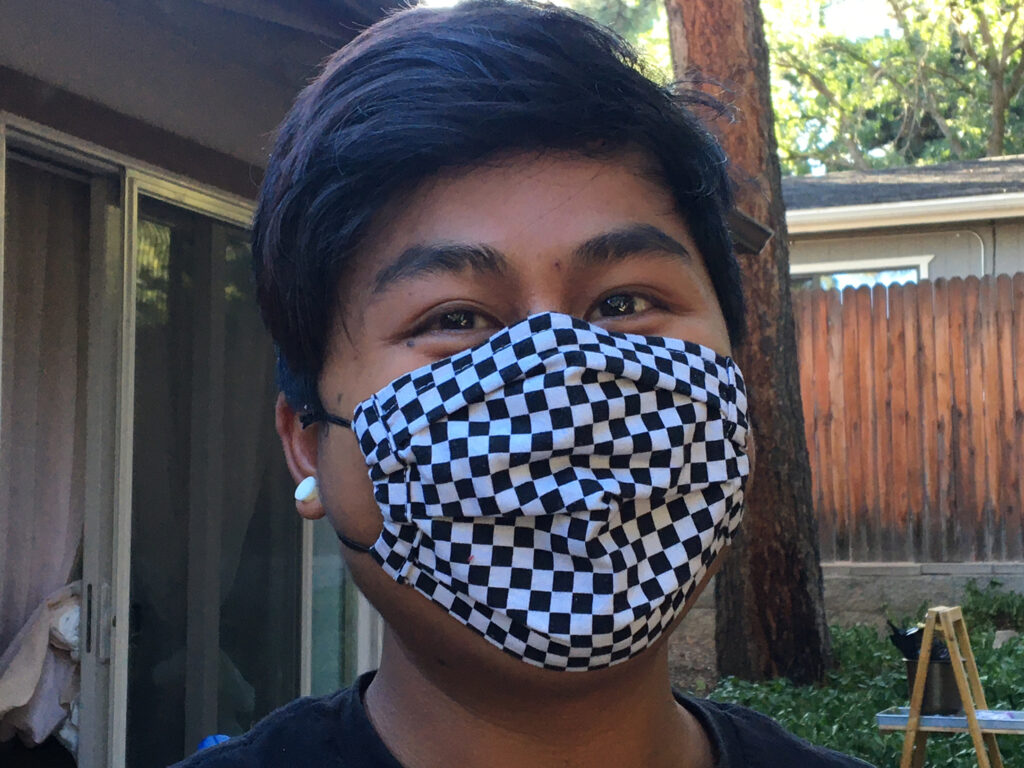

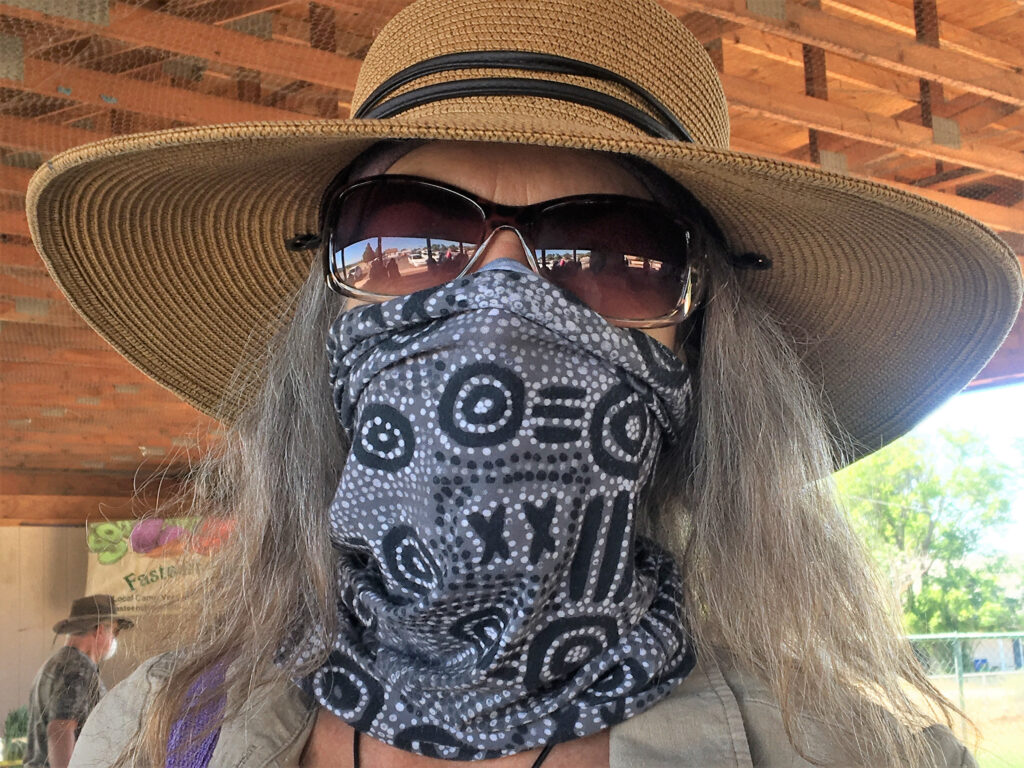

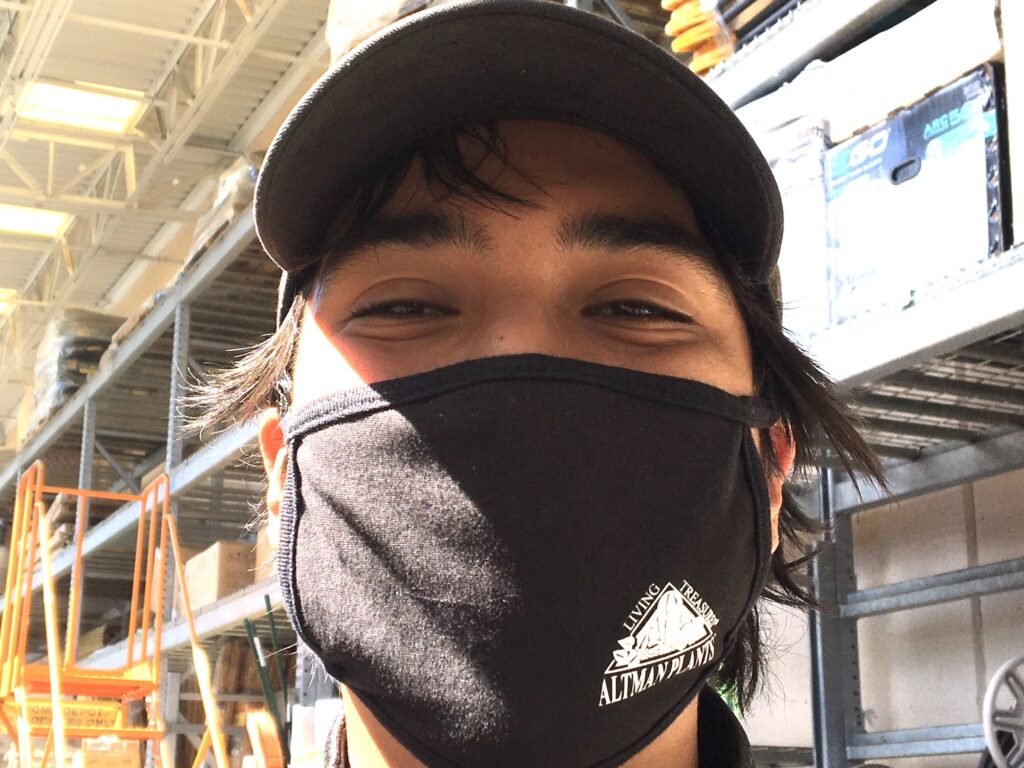

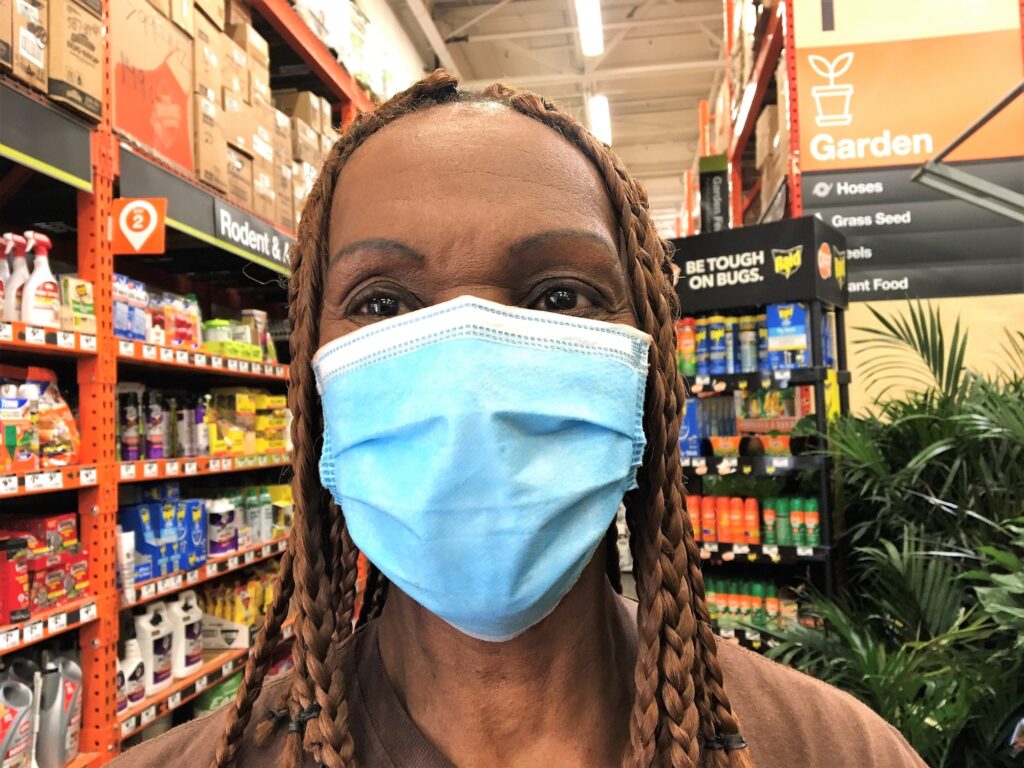

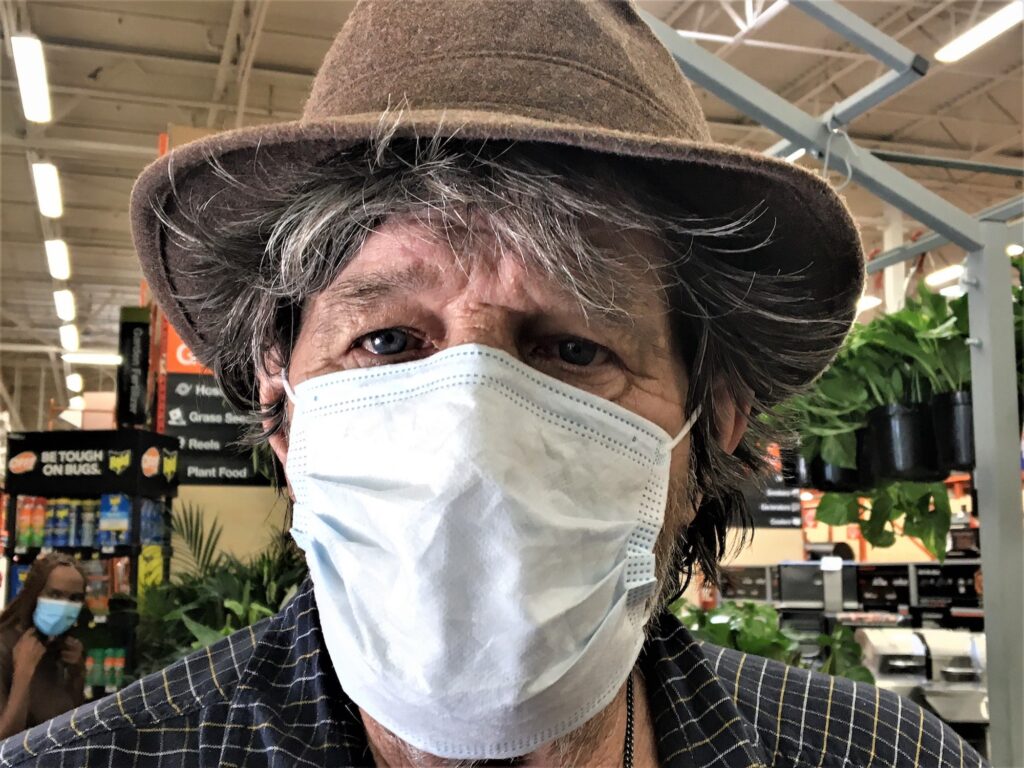

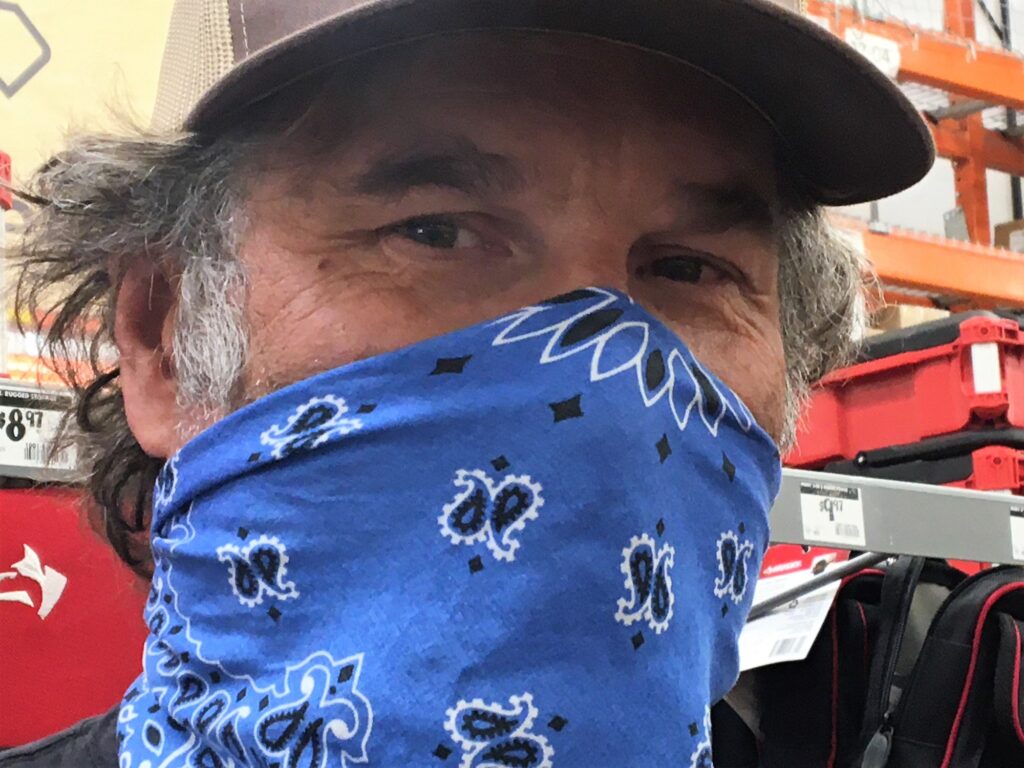

Look at these faces. One of them could be yours. Look at the eyes. What do the eyes tell you that the mouth does not? Eyes are the epicenter of truth while the mouth pledges honesty to no one. Cover the eyes, as most masks do, and leave the mouth free to equivocate. Or cover the mouth with a band of bright color, an American flag, flowers, flames or dinosaurs, and let the eyes do the talking.

(continued below)

So many of our masks are homemade and beautiful, meant to draw attention to themselves. They own their place on the face, and invite a long look and a new kind of seeing. They open conversations.

“That’s a great mask. Did you make it?”

“Gosh no. I don’t know how to sew. My ex-wife made it for me. Well, she’s my former ex-wife. You got time? I’ll tell you a story.”

One man proudly explains he made his mask from an old set of thermal underwear, without lifting a needle and thread. Another wearing a paper mask manages a rakish look. It’s as if the masks inspire us to be other than ourselves, free of ourselves. A woman wearing honey bees talks loudly with another wearing jalapeños. “Can you hear me?” she asks. The other assures her she can. “I’m not used to talking with this thing on.” “You’re doing great,” replies the jalapeños. “Just pretend you’re in a play.”

Every pandemic comes with its offerings, and this one has offered me a new habit of being I call the direct gaze. I used to feel uncomfortable looking directly at people—uncomfortable and a little bit lazy. Wanting to give them some privacy, and wanting to rest from the busyness of faces. An entire face holds so many possibilities. The hair is present, the eyes, the nose, the texture and color of the skin, the turn of the lips, the presence or absence of facial hair, the complicated sculpture of ears. It’s too much to take in, all that face! But masks have reduced the burden; they’ve given focus to one of the most complex areas of the body. They’re like a picture frame on a wall of graffiti. We’ve turned the old story of concealment and disguise on its head, and created a way to see each other more closely, clearly, intimately.

When I first started walking around with my camera and asking masked strangers if I could photograph them, I expected as many nos as yeses. I was surprised when all but a couple of people agreed. Then I realized that as intrusive as a camera could be, the masks were a form of protection—for them and for me. We were four eyes meeting, nothing more than that. Four eyes and that ornamental thing we call hair. And the eye of the camera. That makes five.