An egg is perfect: The flawless curve of its nacreous horizon, the shimmering gloss, so like the Earth’s atmosphere seen in photos from space, of a rounded surface that never ends but is always beginning. An egg holds all the makings for life without any of the messiness to come: The blood, the hunger, the scraggly and wet down feathers of the newborn chick, the insistent screechings for food, the white splashes of feces and ultimate death, whether untimely or long put off. An egg is pure potential, life compressed into compact form and ready to spring out one fine warm morning.

An egg is perfect: The flawless curve of its nacreous horizon, the shimmering gloss, so like the Earth’s atmosphere seen in photos from space, of a rounded surface that never ends but is always beginning. An egg holds all the makings for life without any of the messiness to come: The blood, the hunger, the scraggly and wet down feathers of the newborn chick, the insistent screechings for food, the white splashes of feces and ultimate death, whether untimely or long put off. An egg is pure potential, life compressed into compact form and ready to spring out one fine warm morning.

Which is why I came to think back when I was around 30 that if I had to have a job, then looking for nests would not be a bad one.

This was the job: Every two weeks, drive to an undistinguished office on the outskirts of Phoenix, pick up a big stack of topographic maps and load up the state truck. Tents, sleeping bags, food, a shovel, 20 gallons of water. Drive out through the concrete expanse, into the desert. Our job for the next 10 days was to figure out how to get to the places marked on the maps. Find out what birds are there. Look for their nests. What we are paid to do is learn how the landscape resolves itself into birds.

I’ve never had a better job.

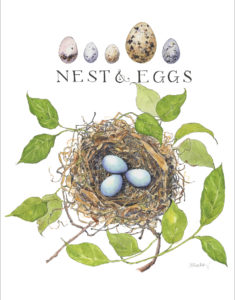

Some nests are easy to find, like those of the common gnatcatchers and house finches and cactus wrens. Some are almost impossible, such as those of the lesser nighthawks that return to the low deserts in spring and flit about for aerial insects every evening. They nest somewhere out in the desert, under a creosote bush that to our eyes looks no different than a thousand others. They scrape out a bare spot and lay two cream-colored eggs spotted with gray. An adult nighthawk, incubating on the ground, is brown speckled with white and looks much like gravel. It is perfectly hidden in plain sight, and spends its time sheltering its eggs from the heat of the sun, shading them with its own body, moving them into slightly denser shade when necessary.

There is no way to look for such a nest. All you can do is walk and hope. In years of walking the desert flats I only once flushed a nighthawk from a nest, and then stood gape-mouthed at the sight of the two eggs, in the heat, under their flimsy shade. It felt like some religious initiation into a rite of the desert¾the wages of all those hours spent hiking and paying attention. Perhaps you can understand, then, why finding eggs can be even better than spotting a bighorn or a badger. They’re a little bit of magic. Eggs hidden in their nest are the future manifest in the present, the unseen heart beating at the center of it all, a curtain pulled aside for just a moment to allow a glimpse beyond.

And, like all good things, they have their season, and their season ends. In the desert, the nesting season comes to an end in late spring, right about now, when the weather grows too hot and dry for adults to shelter and feed their young. Some will nest again if and when the summer rains come. For us field biologists, though, the season of working in the desert was over. We moved to higher, cooler elevations, to the mountains. They have their own allure. But for the rest of the year, for me, hiking in the desert has never been quite the same. With no nests to find, the chances for excitement, for the flush of finding something, are less.

It all comes to a point like that, doesn’t it? Each egg arrives with its clock ticking, with a preprogrammed duration of incubation that has to end in the messiness of hatching. Spring comes to its vanishing point, and the mild days that had seemed so full and so long irrevocably end in the heat of summer. The fledgling birds, if they survive, go off alone, and next year will hatch young of their own.

Youth ends too, as what had seemed the infinity of life stretching toward some unseen horizon comes to seem short, even cramped. Everything begins to incline toward the period, the point where the lines converge and stop.

But it all wouldn’t mean anything if it weren’t for that, would it? Sitting here now, older, remembering the life of the desert, I think of the moment of spotting a falcon, the flash of the hunter’s gun, the thrust of the spear, the surge in the blood. It’s the moment when the lines converge that gives meaning to it all, when the lines of different lives intersect or when the lines of one life reach their final point. It makes me think of the Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset, who has written more insightfully than just about anyone else about the philosophy of hunting. “[O]ne does not hunt in order to kill,” he wrote; “on the contrary, one kills in order to have hunted.” Or, as I’d put it, one does not live in order to die, but one dies in order to have lived.

We can’t know how the view toward the horizon looks to the nighthawk chasing moths against some desert sunset, or to a hummingbird engaged in its frenetic pursuit of nectar and insects. We can’t know whether ravens have their own means of coming to terms with the end of the line. All I truly feel confident in knowing is this bit of information, and we will all have to decide for ourselves what to do with it: an eggshell and a skull are made of the same stuff, as rounded and lovely and vulnerable as the surface of the Earth we walk upon.