While he drove me and my brother to school, my father listened to traffic reports. The newscasters spoke so fast their words smeared together and I always heard, “Inbound on the outbound Kennedy you’re looking at an hour five,” causing me, from an early age, to believe (somewhat correctly) that navigating the Chicago expressway system was one of life’s greatest dangers and mysteries. Beyond this, I found the reports desperately boring.

While he drove me and my brother to school, my father listened to traffic reports. The newscasters spoke so fast their words smeared together and I always heard, “Inbound on the outbound Kennedy you’re looking at an hour five,” causing me, from an early age, to believe (somewhat correctly) that navigating the Chicago expressway system was one of life’s greatest dangers and mysteries. Beyond this, I found the reports desperately boring.

All work commutes are routine, but the commute to and from my job in Flagstaff is the most peaceful of my adult life; one that doesn’t involve lumbering buses or rattling L-train cars stinking of sweat and urine. But for one slow stretch near the elementary school, there is no traffic and no reason to listen to live talk radio saying things like “Inbound on the Kennedy . . .”

At work, I listen to an 11-year-old read aloud John Berryman’s “Dream Song 14:” “Life, friends, is boring. We must not say so . . .”

Each student has been assigned, at random, a different poem to memorize. The boy with glasses too big for his head, the boy who sticks Post-It notes on his classmates, who shifts and slides restlessly in his desk has received this one. I listen to his little voice recite the words as he squirms and twists in his desk and think of Berryman’s delivery—bearded, boozy, droll. I must admit, I’m a little amused.

In World Literature, a senior tells me she finds The Odyssey “boring.” I think again of Berryman: “I am heavy bored./ Peoples bore me, literature bores me, especially great literature.”

So to make things more interesting, we revisit the story of Clytemnestra and Agamemnon. I tell them Clytemnestra was not bored during her husband’s long absence. Unlike virtuous Penelope, Clytemnestra didn’t hole up in a room weaving and grieving; rather, she got on with it. (I’ll admit, I prefer Clytemnestra to Penelope.)

Meanwhile, in my AP Literature Class, Dante issues invectives and heaps metaphorical medieval torture upon his countrymen and kin—“People, friends, are evil, and we must say so.” My high schoolers handle it well. They mostly hate Dante, think he’s a religious zealot, a freak and expect him to be a man of our times despite the centuries between us, but not one student refers to the text as “boring,” at least, not in my presence.

Years ago, when I was teaching an Intro to Creative Writing course at my alma mater, a little liberal arts college in Wisconsin, a student bemoaned, “All literature doesn’t have to be disturbing, you just happen to like disturbing.”

Vaguely offended, I replied that I never said their work had to be “disturbing” but that it had to be “interesting” because “puppies and sunflowers and sunny days are damn boring.”

Maybe I was grumpier then, confronted with the first taste of teaching’s grim reality: Times New Roman assignments, my scribbled comments hanging in the margins, prescriptive. Every night one big autopsy—finding the simile, extracting connotations, diagnosing symbolism.

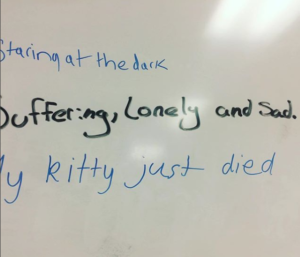

I wasn’t quite 30 and I hadn’t yet been properly disturbed, the kind of disturbed that would make me long for puppies and sunflowers and sunny days. Still, I think, when it comes to literature, and perhaps life itself, puppies and sunny days don’t cut it. Love often doesn’t even cut it. Perhaps this understanding makes me more forgiving of the oft-derided teenage poetry overflowing with “angst.”

If poetry exists to express the inexpressible, to puzzle out the incomprehensible, to order the chaos, why wouldn’t teenage angst find a comfortable home there? Is it not the perfect venue for the messy, tangled, grotesque rat king of feeling that fills our adolescence and young adulthood? Angst is infinitely more interesting than joy.

And I remember that itchiness my students no doubt feel: lying on my stomach in my childhood bedroom reading Wuthering Heights for English class, a million things vying for my attention—my music, my friends, the clove cigarettes I had hidden in my underwear drawer. There were a million things more interesting than Heathcliff whose allure was lost on my gay brain.

As a teenager, boredom grew from the acute awareness of other, better options just out of reach.

Maybe I still feel the itchiness; the truth is, at times, I, too, find The Odyssey boring. Homer, whoever he/she/they were, seems, at times, in dire need of an editor. And there are moments in The Inferno that feel a bit dry, places where I might have written in the margins, “show don’t tell.”

On my commute to and from work I grapple with why I am subjecting my students to any of it. When we are “heavy bored” it is essential to ask, “Why?”

Now in my 40’s, I am seldom bored, but I fear boredom because, as an adult, options abound and boredom is what happens when we’ve grown complacent, tethered to routine, knee deep in the absence of tension, adrift on peace. Boredom is being bereft of stories.

For example: I am one of the few teachers I know who loathes summer break. It’s too uncomplicated. Where is the tension in those blank days? What stories will I tell about the times I slept late, walked the dog, stayed in my pajamas all day and cooked elaborate dinners for my wife?

Good stories cannot grow from simplicity, from peace. Even the ancient Greeks knew peace makes for boring stories and boring ends: The Odyssey doesn’t conclude on a redemptive high note, doesn’t end when Odysseus reveals himself to Penelope—he has to slaughter the suitors, and the servant girls, and then the families of the suitors must want to slaughter him in kind. The story must go on until some goddess says, “Enough.”

On my way to school in Flagstaff, I don’t have to fight for a seat or keep an eye on the guy playing with a pocket knife or shoulder my way through the tired and miserable masses to steady myself against a grimy metal pole. Instead, mountains rise and across from the school a meadow of sunflowers spreads out pastorally. People walk their dogs. Young people talk and laugh as they await the first bell. I often complicate the scene, trouble the calm with music—a little NWA or John Lydon.

When I lived in Chicago and Milwaukee, I used to write often about my commutes. They were rife with tension, with conflict, with grim details, with raw, unabridged, Dantean humanity and never boring. The first day I drove to school here, I remembered those former commutes and thought, “I will never write about this. It’s too beautiful.”