This past weekend I participated in a panel discussion: “Life as a Successful Artist.” When I was first asked to do this a few weeks ago, I balked. I thought about what it means to be a successful artist. And whether (or not) I feel like one.

This past weekend I participated in a panel discussion: “Life as a Successful Artist.” When I was first asked to do this a few weeks ago, I balked. I thought about what it means to be a successful artist. And whether (or not) I feel like one.

Sadly, the success label can kill the creative impulse for some of us. I have to be very careful to apply the label only to my creative projects, but not to myself: success isn’t something I AM, it’s something I HAVE.

It’s critical for me to start from scratch with every new project. Beginning with expectations for an end product – a commodity – means I might avoid taking risks in the making process. Never stepping away from dry land can sound a death knell for my creative projects. Risk and uncertainty course through good, creative work, so it’s better get used to them.

Skillfulness is another question altogether: I do claim proficiency. With every endeavor, I amass more skills and hone them to apply toward future projects: more arrows in my quiver, more tools in my toolbox, more ways to pinpoint exactly the right word or image in service to making a successful piece.

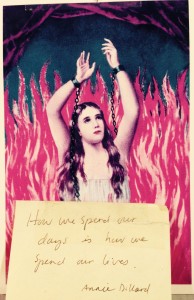

Some days I get out of bed with a fire in my belly for the work. The work inspires me. Ideas grace me with their presence. My obligation is to lavish time and materials on those ideas.

Jill Divine, one of my co-panelists, said it’s an artist’s job to “wring it out,” which I take to mean making the most of the ideas and the materials we have in front of us. She eloquently described her process to the class, talked about inspiration and gathering, girding herself for the work, editing and honing. At no point did she say, “And then, I got paid for the poem.”

Was money the elephant in the room during the panel discussion? Let’s just say that in certain circles “success” is code for “money”. Alas, questions of compensation and the value of work aren’t so easily resolved in our capitalist, pseudo-meritocracy.

A couple of years ago, Tony Norris called me from a garage sale to come and look at what he thought might be a mangle – an electric ironer that was standard equipment in every properly-outfitted 1940s kitchen.

A couple of years ago, Tony Norris called me from a garage sale to come and look at what he thought might be a mangle – an electric ironer that was standard equipment in every properly-outfitted 1940s kitchen.

My husband jokes about my mangle collection. I acquired the first one at a junk store in Cottonwood. The best one came via my friend, Jayne, who lugged it back from Montana one summer for me. No small feat, that, as a mangle generally weighs 75 pounds or more, and is housed in a bulky cabinet. It’s not whimsy or nostalgia that drives my obsession: I use a mangle in the studio when I have a lot of yardage to iron.

Anyway, for $10 I bought the one that Tony spied, then brought it home and took it apart to clean it up and see if I could get it working without blowing any fuses or setting fire to anything. And there it sat, in pieces, until last Saturday when a friend told me about the Flagstaff Sustainability Program’s Fix-It Clinic and suggested I take it in to see if anyone there could help get it back in working order.

I loaded the whole mess into a cardboard box. At the clinic I was hooked up with Jake and Rich, who – with logic, skill, and no small measure of courage, in light of the thing’s old wiring – tested the motor, the mechanics and the electrical circuitry, got the thing reassembled and put a new plug on the end of the cord. I was thrilled. At the very end of the process, we plugged it in. The shoe heated up: victory! We engaged the roller that feeds cloth through the contraption. And…nothing happened. Anticlimax. Jake was pulled over to another project. Rich and I debated about whether to pull the switch out and see what was wrong, but by that time I had to leave to get to the Center for the Arts for the panel discussion.

Even though I didn’t come home with a perfectly functioning machine, I was elated with the progress made, and felt pretty confident that I could figure out how to get the roller switch working again on my own.

And so I found myself wondering how mangle repair equates with the creative process: use what’s in front of you, assemble the parts in a way that communicates the big idea, right? Use all the tools you need to put the thing together, but improvise where necessary. Understand the big picture, but pay attention to detail and excellence. Work steadily and make a consistent effort toward the goal, even when you don’t know precisely what the goal is.

After thinking hard about all this, here’s what I’ve learned: abandon notions of success or failure. Don’t get attached to outcomes, either. Grab a big idea and clamber out on a creative limb, knowing that if that idea is too heavy for the structure you’ll wind up on your ass on the ground below. If that happens, rejoice. Pick yourself up, and begin again.