A few weeks ago I was staying the night at a friend’s house. It was well past dinnertime. Clean dishes nestled into the drying rack, and a spirited conversation had ebbed. My friend’s 6-year-old daughter held my hand as she guided me up the stairs to the guest room.

A few weeks ago I was staying the night at a friend’s house. It was well past dinnertime. Clean dishes nestled into the drying rack, and a spirited conversation had ebbed. My friend’s 6-year-old daughter held my hand as she guided me up the stairs to the guest room.

I kissed her good night and told her I was going to sleep.

“But where do you go?” she asked. I pointed toward the bed. She shook her head. “Where do you go?” she repeated. Her face scrunched into a kiddie mix of confusion and frustration. Again I pointed at the bed.

“No,” she said. “Where do you go when you go to sleep?”

I told her that I stay here, but I go away, and then I come back to the place I never really left. My answer seemed to satisfy her, but as I heard my words aloud, they sounded like something cadged from a fortune cookie. She toddled off to bed, and I tucked into mine, thinking not so much about where I go when I sleep as why getting to sleep has become something I can no longer count on.

Sleep—with its falling and waking—has long had potent gravitational pull for me. I’ve contended with wanderlust since my late teens. I’ve lived abroad, traveled to some of the globe’s tangier outposts, added an accordion of extra pages to my passport. All of the exotica and longitudinal otherness pales beside my all-time favorite place to go: to sleep.

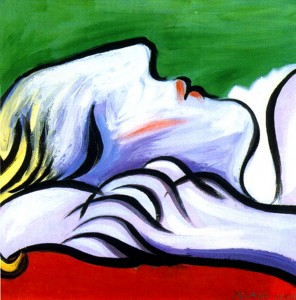

Shakespeare called sleep “nature’s sweet nurse.” Coleridge claimed it as “a gentle thing beloved from pole to pole.” I read once of something called temple sleep, a restorative ritual practiced in ancient Greece. Those who chose to partake made their way to a particular sacred place. They were garbed in white, given a drink purported to induce dreaming and told to sleep the sleep of the righteous on the temple floor. Come morning, they were awakened and all was once again right in their world.

Sleep, such a primal and primitive need, used to come easily and effortlessly. Can I get an amen here? I’ve taken that ease for granted until the past five years or so, when I’ve come to find that there are more and more nights when—despite a still mind, a good bill of health and a clear heart—sleep and all its deliciousness elude me. Even though a good sleep is only enjoyed in the past tense, in the present tense of night when I am primed and ready, it feels sometimes as if my wish to sleep well curls back on itself and interferes with sleep coming my way.

I’m grateful that I am not in the same category as my friend Dee Dee, who has been in a lifelong wrestling match with sleep. According to the National Institutes of Health, about 70 million Americans call their sleep problematic, elusive, a disorder. The occasional sleeplessness, OK, we all deal with that. But years of bad sleep would have rendered my world a caustic shade of grey. I imagine it feeling as if my eyeballs had been rolled in sand and returned to my sockets. And then there is the menu of the brain-related ailments sleeplessness washes ashore in its toxic wake: risky decision making, impaired wit, quickness to irritation, lethargy, inability to focus, slurred speech, hallucinations.

In these last four or five years I haven’t reflected as much on where I go when I sleep as much as I’ve noted how I go to sleep. If fortune favors me, the hamster wheel in my head stops spinning. My anxieties lose their itchy demands for attention. I submit, go gauzy and begin to liquefy. The edges of my physical self evaporate like a darkroom photo being processed in reverse. My mind gets drifty, and I seep away from the world. I float to an enfolding, velvety place alone and surrender. I am unafraid. Sometimes dreams are there; many times not. No matter the cinematics or the duration, I come back gathered, rearranged, able.

On Monday I returned from nine days at an artists’ retreat on a small island in a lake between Minnesota and Canada. The island was unpopulated except for the 10 of us there. No cars or cell phones or alarm clocks. Days full of rain and books and writing. Nights ripe with unbroken sleep.

How can I go there again? How can I get out of my own way and make way for Hypnos to leave his cave and the river of forgetfulness that runs through it?

As I know, it all begins with shutting my eyes.