Spring is the most intoxicating season, even more so in the company of fruit trees. I descend the switchbacks of Oak Creek Canyon in the morning quiet before the tourist cars crowd the road. They are still waking up at their campgrounds, the smoke from their fires signaling a vacation day ahead with coffee and bacon. I stop at Sterling Spring and fill my bottles with the cold, rushing power of water that has just emerged from the earth. Rarely do I find myself there alone, more often I meet others filling jugs and we exchange pleasantries while we share the awe and gratitude of this gift. I study the riparian trees bearing tiny, bright-green fists of spring buds, their uncurling fingers forming a lacy canopy that grows more leafy and exuberant the deeper I descend and with each passing day.

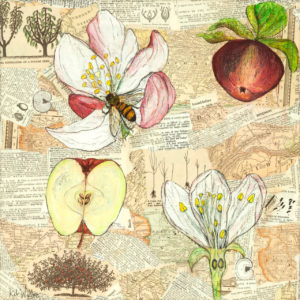

When I get to Garland’s (now renamed Orchard Canyon Lodge) there are fruit trees to observe and tend as they greet the spring and start the seasonal process of growing a crop of fruit. The blossoms unfurl three weeks earlier than normal in response to the unseasonably warm days and then have to hang tough through the sporadic cold nights. The breeze carries their delicate fragrance, and the blushing pink and white flowers stir the honeybees from their slumber. The bees must perform the critical work to transfer the pollen as they buzz between flowers. Most apple varieties are self-unfruitful, which means they need the pollen from a different variety that blooms at the same time. The ovary in an apple flower has five chambers, each of which has two ovules, and most need to successfully be fertilized. If not, the fruit is misshapen or small. Many of the apricots, plums and peaches are self-fertile, meaning they don’t require pollen from another variety and are starting to show that pollination was indeed successful. Thumb-sized fuzzy fruits swell below where the petals have fallen and only shriveled stamens remain.

While I admire the apple blossoms and the steady humming of the bees, I start working on pest control. The coddling moth, our main insect predator, has recently been detected in the orchard on the lookout for a mate. Unfortunately for the moths, I am trying to stop them from having sex. The female lays her eggs on the leaves and tiny fruits and when they hatch, the larvae crawl inside the developing apples and feed on the growing fruit. My job is to install mating disruption dispensers every 10 feet throughout the three-acre orchard. The red rings exude the female sex pheromone, which confuses male moths, hopefully preventing them from impregnating the females. I feel like such a prude intervening in this way; and the plastic tags that affix the red pheromone-loaded rings to a tree branch bear an ironic heart shape. However, the alternatives are worse—wormy apples or the more detrimental spraying of a broad-spectrum insecticide that kills everything, the target pest and the beneficial insects that help balance the entire ecosystem.

Mating disruption technology is relatively new for orchard pest control; it was developed only 25 years ago. Scientists studied pheromones for several decades before a product like this could be released on the market. I am grateful for this and so many other scientific advances that have deepened my understanding of ecology and can help me become a better farmer. This past weekend I marched for science down Aspen Avenue with close to 1,000 Flagstaff residents, to lend my voice to this global movement of citizens calling for evidence-based decision making by our politicians. My sign quoted Simone Weil, the French philosopher, labor union activist and mystic: “Science is the study of beauty in the world.” I also want people to remember that we need to celebrate science with art, poetry, dance, song and the written word.

Every day we live on this planet we reap the benefits of scientific knowledge. It is because of science that I can drink clean spring water flowing from the ground in Oak Creek, that we have choices for organic pest control, and therefore less exposure to harmful pesticides in our food. There are so many factors influencing something we consider so commonplace, such as how an apple makes it into our hands. We need healthy and abundant pollinator communities and scientists who have the support and freedom to do research that advances our understanding of the world, especially as the climate changes, within a society that creates policies informed by science.

Meanwhile, the seedlings in the greenhouse are emerging each day from their little soil cells. Each time a seed I planted emerges from the darkness and starts curling toward the light, wanting to become something, I am filled with joy and a deep sense of fulfillment. It doesn’t matter how many times I witness this simple miracle, I am still filled with wonder. I feel like a proud mother, like I did something right, like there is still magic and hope in the world despite all the terrible news. I feel fortunate to be connected to the rhythms of the Earth and the beauty and complexity of nature every single day.

Kate Watters is a plant enthusiast, writer, artist and musician. She has been a resident of Flagstaff for almost 20 years, and recently took a hiatus to Santa Cruz, Calif., where she was farm apprentice at the Center for Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems. She is now armed with hand pruners and a harvest knife and intends to apply her newfound knowledge and passion to growing all kinds of plants in northern Arizona.