Mr. Philyaw was the cool English teacher, the one with the shoulder-length mane of wavy silver hair, the one the girls talked about, the one who could teach Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance with some authority because he rode a motorcycle himself, as was readily evident on early spring days when you’d see him strolling the halls in his black leather jacket wafting lighting of exhaust.

Mr. Philyaw was the cool English teacher, the one with the shoulder-length mane of wavy silver hair, the one the girls talked about, the one who could teach Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance with some authority because he rode a motorcycle himself, as was readily evident on early spring days when you’d see him strolling the halls in his black leather jacket wafting lighting of exhaust.

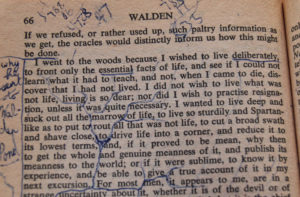

We were reading Henry David Thoreau in those weeks, hacking our way through the thickets of Walden and the famous essay on civil disobedience. Compared to Robert Pirsig and the other adolescent-bait books we read—Catcher in the Rye, On the Road—Walden was a tough slog, and an irritating one.

I think the class was called “The Literature of Introspection,” so naturally all the authors were full of themselves in some way. But Thoreau was in a class by himself, so self-righteously superior toward everyone, rich and poor alike, so prone to crafting entire long paragraphs out of annoying-but-of-course-true aphorisms that didn’t hang together as narrative at all, and barely as a philosophical argument, instead seeming tailor-made not for the 19th century but rather as a marketing machine for the late 20th, with its proliferating bumper sticker slogans and feel-good T-shirts and coffee mugs. Or even the present day, for Thoreau would have been a master of the viral koan-like Facebook meme:

I rejoice that there are owls. Let them do the idiotic and maniacal hooting for men.

We can never have enough of nature.

A living dog is better than a dead lion.

There is an incessant influx of novelty into the world, and yet we tolerate incredible dulness.

Like—or is there a button yet for Grudgingly agree with because the observation is true but painfully obvious?

Still, I was fascinated, in part by the author’s sheer cussedness—he did go out and live by a pond for two years, by himself, which to a reader navigating the shoals of teenage social acceptance seemed an impressive act of independence, if not necessarily a desirable one. The landscape of adolescence was new and challenging. Girls we’d known for years were evolving into new and fascinating creatures, difficult or impossible to approach on the topics we thought most about but interesting to engage in class discussion: “Was it responsible of Henry David to go out and live by himself with no job?”

What stuck with me, though, was the sense of exploration I gleaned from the densely packed pages. It had been a particularly cold and snowy winter in the upper Midwest, and after school I’d often walk down along the lakefront to see how the heaped ice mounds of January and February were slowly slumping and dissolving, giving way to frozen swirls and bumps of sand and small pebbles. It was endlessly fascinating to observe how the long thaw was progressing, a welcome slowdown from the constant high-alert mood at high school, and so when I read how Thoreau too had spent hours watching winter turn to spring at close range—in his case, along a cutbank by the railroad tracks—I recognized a kindred spirit.

“On every hill and plain and in every hollow, the frost comes out of the ground like a dormant quadruped from its burrow, and seeks the sea with music, or migrates to other climes in clouds. Thaw with his gentle persuasion is more powerful than Thor with his hammer. The one melts, the other but breaks in pieces.”

Thoreau didn’t make a living from writing and was widely regarded as a crank during his lifetime, but that didn’t matter to me. What did matter was the realization that someone could spend long hours closely studying a scene that almost everyone else quite literally zoomed by and disregarded, and longer hours crafting his observations about it into respected prose, ready to be analyzed by breathless adolescents a century and a half later.

I still have the beat-up Signet paperback, its inside front cover covered with my homework equations involving sines and cosines that I no longer understand, its sketch drawing of the author converted into a ’70s hippie through my addition of long hair, a beard, and John Lennon sunglasses.

Clearly, I was fidgety in class. On many pages half the lines are underlined, as if to demonstrate just how painfully rich the aphoristic language is. On others I honored Thoreau’s own devotion to detecting patterns in nature and in life by drawing elaborate diagrams of creeks that wound their way down through the spaces between the words, as if to emphasize that the melt and the drip and the thaw could penetrate anywhere, even into a page of densely packed 19th-century prose, even into the icy solidity of a Chicago winter, even into the challenging relations of the hallway and locker room.

Ideas penetrate like water, is what I learned from reading Walden. It’s a lesson very much in mind now as I experience the repeated freezes and thaws of a wet Arizona winter. Around here the thaw isn’t a beast that comes out just once, but a dance involving numerous repetitions: snow, freeze, sun, thaw, repeat.

Which means we get to enjoy it over and over again, whether it’s the mud in the yard, the music of thaw water tinkling down from the roof, or the first flush of green on the willows. The thaw is the forerunner to spring, and each time it’s the same; each time it’s different. It’s like nothing so much as a beloved book that you hang on to because you know you will want to read it again, and when you do you find in its worn pages not only a new exposure to old ideas but a recollection of who you were when you read it the time before, and the time before that.

So I reach the end of Walden, again: “The sun is but a morning star.” As before, I’m still not entirely sure what he meant by that. Maybe I’ll figure it out next time.