Tears matted my hair to my face as I staggered out of the clammy bedsheets ripe with the sour smell of sickness. I lurched toward the bathroom for another round of diarrhea and vomiting; my intestines had been slam-dancing for five days.

Tears matted my hair to my face as I staggered out of the clammy bedsheets ripe with the sour smell of sickness. I lurched toward the bathroom for another round of diarrhea and vomiting; my intestines had been slam-dancing for five days.

It was 1985—40 years ago–and I was alone in Pokhara, Nepal, a small town at the ankles of the Himalayas, the last stop on my five-month solo backpacking trip across Asia. I had been gastro-intestinally blessed until Nepal. But as soon as I checked into the Fishtail Lodge and unlaced my hiking boots after an 11-day trek up Annapurna mountain, I became a victim of giardia, a capricious intestinal parasite. Giardia won’t kill you, but some days you wish it would.

Once again, I folded myself around the toilet bowl and wept. All I wanted was my mom and my bed and a puke-free day. The 10-room lodge had no TVs, no telephones, no books. My days at the Fishtail were spent in a damp delirium of self-pity. I drifted in and out of a sweaty half sleep, bargained with various deities, and waited for Marie, the owner of the lodge. She was a nurse from India who told me she had worked with Mother Teresa on the streets of Calcutta. Marie tapped lightly on my door twice a day to change the sheets and bring cold rags for my forehead. She stroked my face, took my temperature, and encouraged me to eat unsalted crackers so I could get the strength to take a bus to Kathmandu and fly back to the States.

My trip had started as a whim. Or was it an escape? A cure? Earlier in the year, back in Florida, it was the day before my 28th birthday when the magazine I was editing folded, my live-in boyfriend announced he was applying to graduate schools in other time zones, and the frozen pain of my father’s death six months earlier began to thaw.

My unspoken birthday wish was to gaze upon Mount Everest, journal in hand. I needed awe and perspective. I needed far away. I was certain that the vision of the world’s tallest peak would make my tragedies look like bread crumbs. When an unexpected check from my father’s insurance company arrived, I took it as a sign and bought a plane ticket to Japan, China, Hong Kong, Thailand and Nepal.

After about six days of sickness, Marie showed up late one morning. She was rushed, said she was busier than usual. “Tomorrow we have a very special guest in the lodge.” Did she say the name? I can’t remember. I didn’t have the energy to inquire or care.

The next morning, I had moved a rung up the wellness ladder. My head was still swimmy and I was weak, but I felt pangs of hunger for the first time in what felt like a long time. I pulled on a rumpled T-shirt, mowed my teeth and raked my hair. I wobbled to the dining room and sat at one of the wooden picnic tables, fingering sugar packets and staring warily at my unbutttered toast. The room was empty, except for two beefy guys in flannel shirts. Outside the large windows, the Himalayas looked like a National Geographic photo spread. Maybe I could curl between those snowy, sheltering peaks, wedge into a crevice, and watch my sorrow vaporize in their enormous shadows.

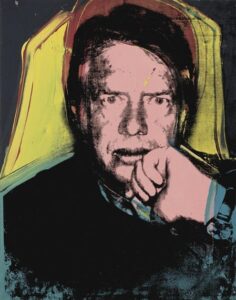

“May I join you?” a voice behind me asked. It was distinctly American, softened with a Southern twang. I looked up. It was Jimmy Carter with a teacup in his hand and a map tucked under his arm. Jimmy Carter. I recognized him immediately: those teeth, that smile.

“Marie tells me you just did part of the Annapurna trek,” he said as if we were all neighbors. “I begin that one tomorrow and I’d like to hear how your trek went.” He unfolded his hiking charts like a kid with a treasure map. “Tell me everything,” he said as he filled my teacup.

And so, we talked with the instant ease travelers so far from home allow. No world politics, hostages in Iran or Reaganomics. My sickness suspended my self consciousness and silenced the questions I would normally have spilled during a serendipitous one-on-one with a world leader. That morning Jimmy Carter was only a fellow trekker, a blessed diversion from my sickly self, and a kind man who listened as I talked.

I told him about the huts where I had slept along the way. The moleskin that had saved my blistered feet. The best kiosks for buying chocolate bars and bottled water. I warned him of recent mudslides on a particular pass and told him about a shop in town that rented tents.

We were on our third cup of tea when conversation widened to the big picture. I talked about my father, my grief, the lure of the big mountains. He nodded solemnly. He spoke about his own quest for peace and adventure that had brought him here on a solo trip after leaving the presidency. We joked and called ourselves pilgrims. Then we sat silently, staring out the window. “They make everything so small, so unimportant, don’t they?” he asked.

We smiled ruefully at one another. Then he reached over and squeezed my hand. He said he hoped I would feel better soon, find answers, get on with things. “It sounds like you need to go home,” he said. I did. It was the only place that could begin to heal me. My eyes filled with tears, and I thanked him.

And I remember marveling then at the unforeseen magic that happens in the most unlikely places in the sphere of an instant when it all becomes so small and so large at the same time.

###