Of course it dates me to describe a time and place where a cold draft of a tame American beer was the answer to the summer end of day craving of a GS 3 firefighter in a mountain town. But it was the early ’80s and we liked our tall Buds in brown bottles and cold cans of Olympia. Heineken was as close as we got to differently brewed. There weren’t the 50 or 60 names of beers you find on menus now. We climbed onto bar stools and nodded and the bartender knew if there was one in the well left over for you from the night before, bought by a buddy when your hand was already full, or stored courtesy of someone who wanted to settle an argument with a small peace offering.

Of course it dates me to describe a time and place where a cold draft of a tame American beer was the answer to the summer end of day craving of a GS 3 firefighter in a mountain town. But it was the early ’80s and we liked our tall Buds in brown bottles and cold cans of Olympia. Heineken was as close as we got to differently brewed. There weren’t the 50 or 60 names of beers you find on menus now. We climbed onto bar stools and nodded and the bartender knew if there was one in the well left over for you from the night before, bought by a buddy when your hand was already full, or stored courtesy of someone who wanted to settle an argument with a small peace offering.

I didn’t keep a cue stick behind the bar like the fellows, but when I settled my green Nomex pants onto a stool at the end of the bar where Crown King locals dwelled, I’d nod, too, and the bartender would bend to a nook under the cash register to retrieve for me, The Book of the Saloon, a five inch by six inch blank book of pages thick enough to hold watercolor, but not so thick a black marker wouldn’t bleed through the pages a bit. So I used pencil mostly, putting a line onto the page to show the beard of Steve who described what route he would take if he rode off the mountain to Idaho one day. I’d blacken in the cowboy hat of the fellow next to him who nodded thoughtfully and mused aloud about water along the way.

After a day at fire lookout, after riding my 125cc of motorcycle to town the back way through summer cabins, past old mines and the one-room school house, I’d nod and Bob would put The Book of the Saloon and a cold mug of Miller in front of me “from that guy last night who liked your drawing of Jean’s package of Lark cigarettes.” Bob might scratch his beard a bit as I sketched the lines that showed clouds building over the gap and trees against the rock face above the dirt road, adding dabs of watercolor to capture the way weather hovered over the 27 miles of dirt road to our saloon. “Here you go Rukkila-bird,” he’d say, putting the next mug down beside me. “On the house.” Then it took a full page to preserve for posterity the kindness of a free mug of foaming beer.

In a town of less than 100 familiar faces the saloon was our living room: the community center where gossip buzzed and locals nested and on weekends a live band stirred it all together into a lively, healing throb of flatlanders wide-eyed and willing, neighbor getting over argument with neighbor, Forest Service bosses nodding at newbie complaints and perfuming it all, the air through the gap pushed against our faces on the porch, mountain air flush with cumulus downdrafts hinting at rowdy weather.

Weeknights the pool table ruled. I tried to preserve the way an arm and fist steadying a cue stick seemed to emerge out of the dark like a monument to concentration, but when I look at the drawing now, it’s the sounds that come back to me: the guffaws aloud and the balls rolling across the pool table translating another whole language of bets and exchange, beers won with a delicate kiss of cue ball off a railing, or beers added to things to just flush the situation to a different level of competition and tenderness.

Weeknights the pool table ruled. I tried to preserve the way an arm and fist steadying a cue stick seemed to emerge out of the dark like a monument to concentration, but when I look at the drawing now, it’s the sounds that come back to me: the guffaws aloud and the balls rolling across the pool table translating another whole language of bets and exchange, beers won with a delicate kiss of cue ball off a railing, or beers added to things to just flush the situation to a different level of competition and tenderness.

And I captured the night a TV was added to the mix. Strange to think now when there’s hardly a bar on the planet without a screen glowing its weirdness over the heads of people who might or might not be talking to each other. It was new and much talked about then, adding a TV to the bar. I drew the darks and lights of the rectangle of it next to the triangles of a glowing Budweiser sign. I added the detail, “Steve watches Loretta Lynn sing a song for Bob Hope’s birthday. May 23, l983.” Bob Hope alive seems a quirky ancient detail. But then so is the ash tray next to Steve’s knuckles.

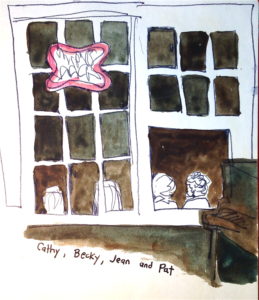

I’m surprised I took the book with me after my seven seasons working for the Prescott National Forest. I probably meant to leave the drawings with Bob as a thanks for the free beers and company. But there are still 20 blank pages in The Book of the Saloon so maybe that was the plan all along. Those pages nudge me to get back up that dirt road one day. Sit a spell. I hear there are rooms to rent upstairs now; one can bed down where the business of a brothel was once one of the flavors of the Crown King Saloon. I won’t find Steve at the end of the bar, of course. I believe he finally did ride a horse all the way to Idaho. And Bob sold the place years ago. Probably newer trucks pull up to the door these days. And on the bench outside? I won’t find Cathy, Becky, Jean and Pat. But others linger there, surely, breathing in a summer night where a cold brew offers a clammy kiss to a pleased hand.