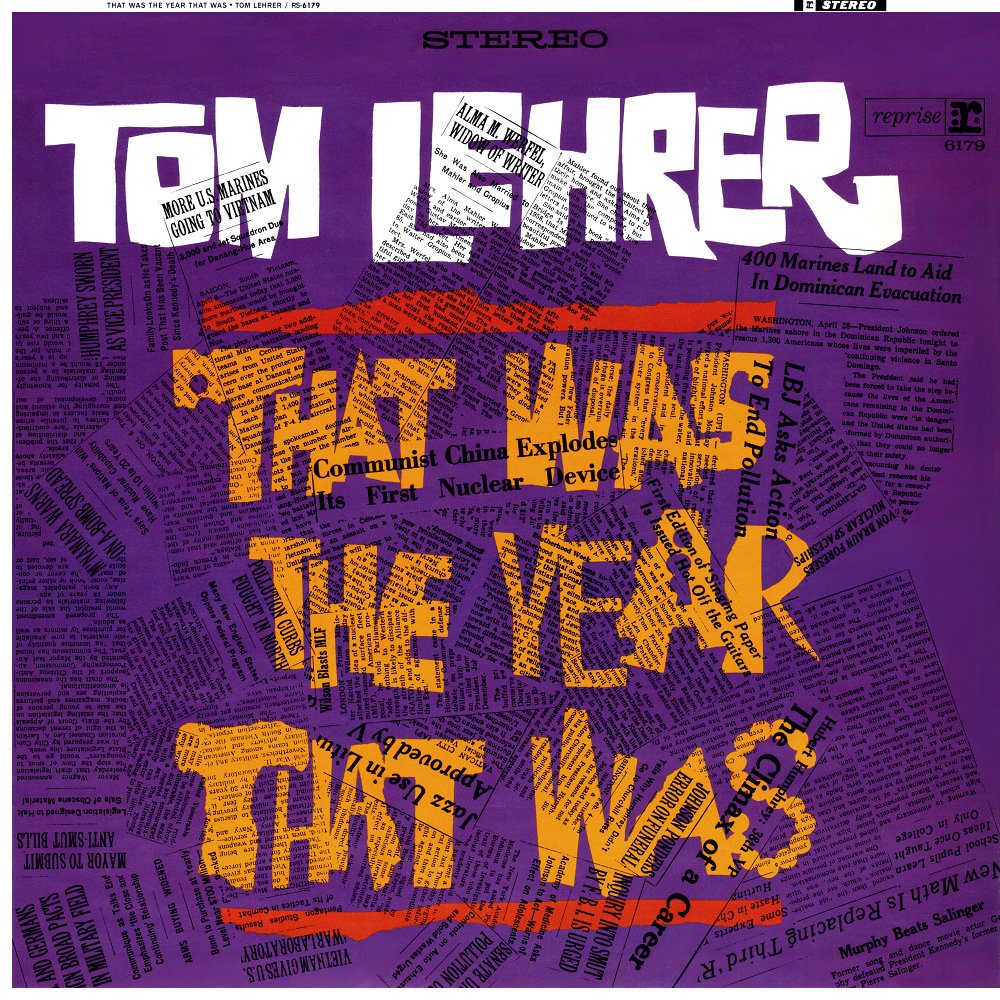

My favorite among my parents’ extensive LP collection was a goofy Tom Lehrer record titled That Was the Year That Was. The year referred to was 1965, at which time I was barely toddling and certainly too young to appreciate satire. But the witty songs by one of America’s greatest satirists stood the test of time into the 1970s—and clear through today, for that matter, when I can still recite verbatim lyrics like those that memorialized the German rocket scientist Wernher von Braun, the developer of the V2 rocket who during Lehrer’s The Year That Was was busy helping NASA design Apollo rockets:

Once the rockets go up

I don’t care where they come down

That’s not my department

Says Wernher von Braun.

The songs were barbed and a bit dangerous, a lesson my parents learned to their chagrin after one dinner party, when they realized that the lyrics to the song called “The Vatican Rag”—

Get in line in that processional,

Step into that small confessional,

There the guy that’s got religion’ll

Tell you if your sin’s original

If it is try, playin’ it safer

Drink the wine and chew the wafer,

Two, four, six, eight,

Time to transubstantiate!

—might seem just a bit offensive to the guests they remembered too late happened to be Catholic. I couldn’t explain, then, what “transubstantiation” was, but it seemed to carry a mysterious weight commensurate with all those syllables.

Which is a way of saying that when it comes to remembering a Year That Was, as we are all doing now in our own ways, it is good to remember that the happenings we regard with an exclamation point might seem to others to close with a question mark at best, or perhaps an angry face emoji. Like the election outcome, for example. It left me and most of the people I know with a feeling of hope but seems to have convinced many millions of fellow Americans that the only way Donald Trump could have not won the election was by some equally mystical transubstantiation featuring Sharpies, rigged voting machines, and the late Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez, whose death seven years ago was apparently no impediment to meddling in this year’s vote.

It is with some trepidation, then, that I take up pen—or cursor, more accurately—to write that one of the principal exclamation points that I plan to remember for this year is a recent one that really did look something like a triple punctuation mark. I mean the three tall smokestacks of the Navajo Generating Station, built about the same time in the mid-70s when I was listening to Lehrer’s “Pollution” in our suburban living room:

Just go out for a breath of air

And you’ll be ready for Medicare!

which meant that they were standing in place, seemingly permanent, well before I got to Page for the first time, in 1990. They were certainly there some ten years ago when my friend Tim and I backpacked up the Paria River from Lees Ferry and took the steep Salsipuedes route out, a lengthy scramble up a sand dune that as we huffed and wheezed with heavy backpacks seemed to amply reflect the name originally given by the members of the Dominguez-Escalante expedition back in 1776: “Get out if you can.” We did, hauling our weary asses up over the final rocks, only to be greeted at the top, at dusk, by the site of the majestic power plant looming surprisingly close, its mercury vapor lights lighting up the evening sky more than the lights of the metropolis of Page itself.

During the daytime the stacks seemed smaller, even their 775-foot height dwarfed by the majestic scale of the surrounding sandstone landscape and the symmetrical dome of Navajo Mountain off to the east. But what was hard to miss was the yellow smear of pollutants that issued from the stacks, a plume that each year carried within it tens of thousands of tons of nitrogen oxides, more than 500 pounds of mercury, and more than 15 million tons of climate-altering carbon dioxide. It was one of the largest single producers of CO2 in the country, and it measurably reduced visibility in the area’s scenic national parks.

The power plant was decommissioned a year ago, its impressive megawattage of coal-generated electricity no longer able to compete with cheaper natural gas and renewable energy. That was some good climate news during a presidential administration that showed more desire to accelerate than decelerate climate change.

As we go into 2021, then, I like to think of the image of the three tall exclamation points standing tall last Friday morning, then with at-first small puffs of smoke beginning to lean, ever so slightly, and then falling to the side at a surprisingly stately pace, before disappearing in a massive cloud of dust that in that open landscape brought to mind lingering images of other explosions we have caused in other deserts as we conduct foreign adventures in the Middle East. I knew from the Facebook video I was watching that this controlled demolition—good news though it is for the struggle against climate change—was attended by both joy and sadness, for many people in Page and in the northwest corner of the Navajo Nation earned a good living at the plant and felt a justifiable pride at the work so long done there. For some, I know, this ending to an era at the NGS is not best closed off with an exclamation point, but with something else.

And maybe the best ending is after all an ellipsis, the line of three periods that stretches off into the vague distance . . .

Because who I was thinking of as I watched was the Navajo woman, close in age to me, whom I interviewed outside Page a few years ago for a magazine story. She was a member of one of the families living closest to the plant, and was planning to build a house nearby despite worries about pollution, about coal ash, about what seemed to be high asthma rates among children in the local LeChee Chapter. This was before the plant’s closure, when officials and local residents were expecting that it would operate at least into the 2040s.

Didn’t matter, she said. This was her place, and her family’s place, and she was taking the long view. She hoped to outlast the plant.

As we all might hope to outlast This Year That Was, and the upheavals it has brought, as we head into what we always have to think of as

. . .

even as we do all we can to make it

!!!