The Boss, Chuck, Jeff, Chris and I sat in the shade of pine trees with lunches at our knees. A couple of the fellows enjoyed wife-wrapped leftover chicken and Tupperware squares of salad from home gardens. Jeff the Vegetarian smelled like garlic but not because of his lunch. He wore cloves around his neck to prevent something, I forget what; perhaps he dared illness to approach his sturdy, muscled body. Chris ate grapes as if each one held a bubble of fortune. I chewed my PB&J while peering at a worn paperback of Robert Frost poems, and I read on through the lunch-hour naptime of the others. They pulled hardhats over their faces and sprawled across the seats of the crew-cab truck, their boots hanging out through open doors. Jeff looked disgusted and marched around kicking pine cones until he eventually leaned against a tree and closed his eyes, too. Then I pulled out my journal and drew a bit, capturing a hardhat askew and hands locked behind a head, how a Forest Service radio could be propped against a mound of pine needles. We worked hard out there, but stayed ready for afternoon fires and rarely saw anyone on weekdays in the woods.

But on this afternoon, the low growl and thump of an unknown truck made us lift up our heads in unison. We glanced at the boss to see if this arrival might be a reason to look like attentive federal workers, but he didn’t look concerned. A well-used white pickup stopped in the dirt road by our tools. A beanpole of an old man unfolded out the door. The boss smiled and they shook hands, murmuring greetings, and settling back to pay squinty-eyed attention to the rolling of cigarettes. Over the sprinkling of Prince Albert into papers I looked at the truck. It had the kind of dents and scrapes that defined good-old truck to me. The frame was askew; the bed twisted slightly over the wheels, the cab torqued the opposite direction. The man’s face, too, was worn: lots of lines moved as he talked to the boss. I moved my pen to make a circle of headlight against the curves of fender and hood. I included the door not quite true and the handle missing a screw. Chuck watched me, then snatched the book from my hands to show the boss. The stranger smiled at the page, and I decided to give him the drawing even before Chris suggested it.

“Yeah, that’s surely Ray’s truck,” the boss said. So I wrote “Ray’s Truck, Prescott National Forest, June 1977” on the drawing and tore it out of my journal. Ray folded it and put it into his shirt pocket and looked at me shyly. “Over my heart,” he said, and patted it. He drove away, and we went back to cutting fuel break and piling slash. Later when we broke for water and smokes and tailgate sitting, the boss told us about Ray.

“They told him to write poetry down at the mental hospital in Phoenix,” he said. “Keep him sane, they said. He writes this stuff all the time.” He pulled a folded paper out of his wallet. “The Bard of the Bradshaws, Ray Nichols, Cleator, Arizona,” it said under five handwritten verses. Chris and I read “The Match” silently over the boss’s shoulder, until I speak the first lines aloud so that Jeff the Garlic Guy can hear it. “It is such a very little thing/We use it oh so much/ Fire is a friend to us/ It is a useful crutch.” Jeff frowned to wave off the rest of the verses.

“Why is he nuts?” Chris asked.

“He mined down by Cleator,” the boss said. “He was a blaster. He made a mistake one day and killed his partner. Spent time in Phoenix to get over it and they told him to write poetry.”

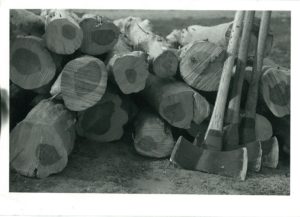

A week later we are back on Lane Mountain cutting juniper poles to peel for a fencing project. The truck drives up again and this time the boss doesn’t stop what he is doing but keeps hacking at particularly stubborn bark. “You could look all over the forest and not find a tougher one to peel,” Ray says. “Little tweety bird put a hole in it. Let the sap out.” He takes the axe from the boss and demonstrates how to slip the blade in under just so, then slides a five-foot length of bark off leaving the naked log gleaming. The boss bucks up more pieces and we all pull axes from the cache to try peeling ourselves. We sweat and joke trying to make long strips like the ones falling around Ray’s legs. It’s hard to get the hang of it. My blade keeps catching in the wood so my log looks beaver-chewed. I’m relieved to see the others are standing by roughed-up poles with chips around their feet, too. The boss just grins and it occurs to me maybe he’d invited Ray out to give his cocky crew a lesson in humility.

“Well, Little Lady,” Ray says, and I expect a smug patronizing remark about women and double bladed axes. “I’m off. But first I have a poem for you.” Ray wipes his sweaty forehead and stands to read in a slightly high voice, the axe he was using leaning against a knee of his dirty fatigues. “Lane Mountain, Arizona. Princess Jean …” He looks at me over the paper. I stand there in my hard hat and gloves, feeling slightly sheepish, afraid my crewmates will snicker. “Lovely lady from the big town/How do you like the hills?/The Bradshaw Mountains are my home/They have many frills.” His sing-song lines grow louder. “You must be brave beyond compare/To join a fire crew./It can be very dan-ger-ous/But this you already knew.” By now I feel the red burning up my neck out of my denim shirt to my warm ears. My brain blurs through a handful of lines until I sense him soaring to an ending. “Be happy, dear, and carry on/Be guardian of our trees/They bring peace to many souls/They cannot help but please.” In the silence after I expect hooting, but the fellows shuffle toward their tools while I look at the page Ray put in my hands. A door slams and the truck coughs its way onto the road and rolls away.

In my bunk in crew quarters that night, I read the lines again and stared at the cracks in the ceiling and thought until sleeping about sanity and trees and tragedy, poetry, how sing-song lines and long dirt roads might name a path to healing.

Arizona-born Jean Rukkila is a retired fire lookout who writes from coffee houses, camp sites and libraries. See more of her writing at www.flagstaffletterfromhome.com.