My neighbor took a panel of siding off his house a few days ago in order to replace an outdoor faucet. Because I’m a bit of a structural archeologist, I was curious and went over early in the morning to take a closer look. The first layer under the siding was stucco, and under that, chicken wire. It was old chicken wire, a different gauge than you see today. Under that layer was wooden clapboard. I recognized it as the same narrow clapboard I’d found under the stucco at my house. It was unharmed, sound, in perfect shape. If you wanted to, you could strip that house down to its clapboard bones and it would be as eye-catching as it must have been 100 years ago.

My house was built around 1898. I have an old photograph of this neighborhood, the original townsite built sensibly around a perennial water source that’s perennial still. The water flows out of the ground over on Lower Coconino, a clear and I assume clean little life-giving spring. The old photo shows the junction of Grand Canyon Avenue and Santa Fe, both of them dirt roads, and a dozen houses north of the railroad tracks. Santa Fe heads straight out of the picture to the east, past the lumberyard, following the line of the tracks. I don’t know the year this photograph was taken, but earlier than 1916. My house looks like it’s in its original Workingman’s Foursquare style, before the 1920s addition that gave it a kitchen and an indoor privy. It has a dormer, which indicates a living space in the attic. In the old days, many people used the attic as an overflow bedroom because homeowners were taxed according to the number of bedrooms in the house, and the attic didn’t figure in that number. If your attic was spacious, as mine was and is, you could run a regular dormitory up there and still keep your taxes low.

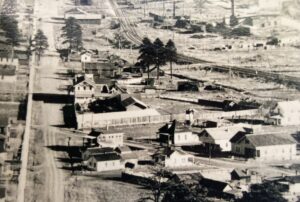

My house was built around 1898. I have an old photograph of this neighborhood, the original townsite built sensibly around a perennial water source that’s perennial still. The water flows out of the ground over on Lower Coconino, a clear and I assume clean little life-giving spring. The old photo shows the junction of Grand Canyon Avenue and Santa Fe, both of them dirt roads, and a dozen houses north of the railroad tracks. Santa Fe heads straight out of the picture to the east, past the lumberyard, following the line of the tracks. I don’t know the year this photograph was taken, but earlier than 1916. My house looks like it’s in its original Workingman’s Foursquare style, before the 1920s addition that gave it a kitchen and an indoor privy. It has a dormer, which indicates a living space in the attic. In the old days, many people used the attic as an overflow bedroom because homeowners were taxed according to the number of bedrooms in the house, and the attic didn’t figure in that number. If your attic was spacious, as mine was and is, you could run a regular dormitory up there and still keep your taxes low.

In the photograph, my neighbor’s house is right there next to mine. It’s configured a little differently, with an overhang and a porch facing north to keep the house cool in the summer. And sure enough, when I stepped back and looked carefully at the present building, I saw the remains of a porch slab and front steps leading out to the street on the north side. People would come by on horseback or in one of those new-fangled automobiles, and sit a spell on that porch in the summer, and gossip and watch the neighborhood going about its business. Which is pretty much what we still do.

Many of our old houses are now sided with t111 panels, or stucco, or asbestos, or vinyl. Every now and then you see a run of old shiplap or clapboard, and even more rare, board and batten. But whatever the current clothing of a building, whatever its temporary skin, not far from the surface lie the bones of it, the frame and joists, the enduring foundation (mine is built like a sloppy stone wall, rock wed to rock by an abundance of cement). Old homes have good bones. Perhaps I’m more of an architectural orthopod than archeologist. I like to see what the body’s made of, the structure that keeps it upright, the idiosyncrasies that require the floor to sag. I’d be skirting the truth if I didn’t say how much I love an old house for its metaphoric qualities. The pipes that bring sustenance — water, warmth — and remove what we no longer need; the yellowed newspapers and rags, cast-offs finding purpose anew in insulating our walls; the floor that relaxes, that refuses the level and allows us the experience of imperfection; the windows that stick and groan, yet bring us breezes and birdsong; doors that offer us, yes or no, the world.

Many of our old houses are now sided with t111 panels, or stucco, or asbestos, or vinyl. Every now and then you see a run of old shiplap or clapboard, and even more rare, board and batten. But whatever the current clothing of a building, whatever its temporary skin, not far from the surface lie the bones of it, the frame and joists, the enduring foundation (mine is built like a sloppy stone wall, rock wed to rock by an abundance of cement). Old homes have good bones. Perhaps I’m more of an architectural orthopod than archeologist. I like to see what the body’s made of, the structure that keeps it upright, the idiosyncrasies that require the floor to sag. I’d be skirting the truth if I didn’t say how much I love an old house for its metaphoric qualities. The pipes that bring sustenance — water, warmth — and remove what we no longer need; the yellowed newspapers and rags, cast-offs finding purpose anew in insulating our walls; the floor that relaxes, that refuses the level and allows us the experience of imperfection; the windows that stick and groan, yet bring us breezes and birdsong; doors that offer us, yes or no, the world.

When my neighbor appeared I was still standing in his driveway, staring at his house, which he found unusual if not a little disturbing. But then we got into it — it turns out he’s a structural archeologist/architectural orthopod himself. I noted the old and very possibly original clapboards and he said, “Take a look at this.” He picked up a piece of the old wood and showed me a cross-section. “See this?” I did see it. It was a joint created to bring two boards into harmony. “That’s a rabbet joint,” he said. “You see that with shiplap, not clapboard.”

“Oh?”

“Shiplap is rabbeted. A rabbet joint is used to make it sit flush. Clapboard’s got a thin edge and a thick edge and no intention of sitting flush. It overlaps. It goes up one board at a time. It doesn’t need a joint like shiplap does. I think what we’ve got here is shiplap, ‘cause gosh, if that’s not a rabbet.”

![]() Here was a true believer, I thought, a house nerd extraordinaire, someone who on the surface of things was an older-than-middle-aged man in a blue button-down shirt, neatly pressed trousers and a pair of leather work boots. He was a mild man, an awkward conversationalist, and if you stopped there you’d never know what he was made of, what lit him up. We were all old houses walking around — a little worse for wear on the outside, a little changed by time and circumstance. Some of us had been carefully shored up to last, others had endured years of cheap siding and thin paint. The mystery of us was often several layers deep, under the t111, under the stucco and chicken wire. But dig down, lean in, and there we were with our hidden virtues, our original and individual natures. There we were with our rabbeted joints, our elegant clapboards, our walls stuffed with old Sears catalogues and dross.

Here was a true believer, I thought, a house nerd extraordinaire, someone who on the surface of things was an older-than-middle-aged man in a blue button-down shirt, neatly pressed trousers and a pair of leather work boots. He was a mild man, an awkward conversationalist, and if you stopped there you’d never know what he was made of, what lit him up. We were all old houses walking around — a little worse for wear on the outside, a little changed by time and circumstance. Some of us had been carefully shored up to last, others had endured years of cheap siding and thin paint. The mystery of us was often several layers deep, under the t111, under the stucco and chicken wire. But dig down, lean in, and there we were with our hidden virtues, our original and individual natures. There we were with our rabbeted joints, our elegant clapboards, our walls stuffed with old Sears catalogues and dross.

“Better get this faucet in before the rain comes down,” said my neighbor. I left him to it.