I went up to Standing Rock Reservation in Cannonball, N.D., to join in the alliance of Water Protectors, one more among thousands. We gathered here to protect the Missouri River from the Army Corps of Engineers, putting water in jeopardy for all downriver. The Dakota Access Pipeline is the “monster” whom we are here to defeat in peace. To speak for the voice silenced, the Standing Rock Lakota. I feel a great urgency to share in this experience and try to bring home the magnitude of our collective struggle.

We arrived on a cold and deceptively sunny morning onto the road leading to the main camp. As we topped the hill into the encampment, we were presented with a powerful vision of the Oceti Sakowin (Seven Fires), the sprawling camp of protectors as far as the eye could see. Tipis, yurts, geodesic domes and large service tents of all kinds among smaller ones. Vehicles and horses and the drone of chainsaws cutting wood for various camps that made up the whole. Flags of all tribes and nations lined the whole area. Signs of support and signs of defiance.

We drove in and were directed to an area where all newcomers are encouraged to take training in a non-violent, direct-action workshop, for this is ceremony and strength and reverence are primary in the actions of the Water Protectors. Weapons are banned, as are drugs and alcohol. I saw the energy of Burning Man, Woodstock and 100 Navajo Nation fairs. Above it all was the sense of holiness. It was likened to entering the healing hoghaan of my own people. You immediately felt the love and support of all the inhabitants, for this brought like-hearted people with one purpose and passion to stand in honor of the water and the sacred burial grounds upon which this whole pipeline issue is central.

I participated in the training which included prayerful encounters, safety, watching one another’s back, pepper spray care, and legal information concerning possible incarcerations—essential things to know staring into the jaws of the Black Snake, as the pipeline was dubbed.

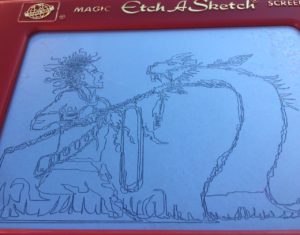

I spent my time in the camp of Indigenous Peoples Power Project, where the art center is. Young people from all over the globe gave the environment color, sound and hope. In the days that followed, I was teamed up with two other artists to create a banner for a concert there. Creative juices pumping the adrenalin. My community for sure.

The memorable and amazing feat of running from Flagstaff to Cannonball, 1,300 miles. These young men of our tribes ran. I saw them leave and had the honor of greeting their arrival at the camp. I later ate with them.

Donation centers cared for the campers as we unloaded our frequent supply runs into Bismarck—supplies of food, firewood and water as well as bodies. None seem to be wanting of supplies as we were all fed well in the main mess tents, as well as in our own camps. There are more than 70 tribal and organizational camps.

Our first full day there ended with a confrontation on the Backwater Bridge, a contentious avenue into the camp from the north that the Dakota Access Pipeline had blocked with burnt vehicles, jersey barriers and razor wires.

In the gloaming of the day, voices shouted for all Water Protectors to the bridge. I stumbled my way there, hurriedly along with two traveling companions. My complicated night vision was further impeded by large rays of lights from the military side of the bridge. Figures running, voices shouting in the night coupled with sirens of ambulances taking injured people away. The early night filled with pepper spray and concussion grenades, rubber bullets, and water cannons sprayed into the peaceful blockade filled with chanting and dancing despite the onslaught of the law enforcement. I scrambled up on the hillside for a better vantage point, but all was confusing. There was a huge cloud of water and mace, and the sounds of rounds being fired into the crowd turned the night into a hellish cacophony of cries as I helped run water to the medics assisting in the melée. Someone took me by the arm when they saw I had blood on my face—my nose bled in the bitter cold, that was all. My traveling companions were out assisting as well, carrying freezing people with slabs of ice hanging off them to the fire where they were taken away by the medics. We had boxes of Milk of Magnesia as a pepper spray remedy. The voice from the other side booming through the speakers, commanding us to fall back, fell on deaf ears. The munitions and water hoses continued relentlessly. We were dancing in to the vengeance of Morton County law enforcement and the DAPL security. In the failing light, I saw tears and firm convictions on faces of our people. Strangers fell into each other’s arms in comfort and warmth to the backdrop of brutal confusion. It’s complex enough in the daytime, this direct action thing. I heard that a woman lost her arm and many were injured. There was no reason to use water as deterrent in that temperature. I see images of Sand Creek, Wounded Knee, Fort Sumner—all the places our hearts still mourn.

Somehow we all slept that night. I trust that everyone found warmth. I shared a tent with a new friend for comfort and warmth. We all watched each other’s back.

The next few days remained quite tense as the militarized police lined the hilltop, the sacred burial grounds of the elders. Marches and rallies are happening daily, including in Bismarck, the state’s capital. We seem to have the numbers; they have the lethal weapons. The plane circled overhead far into the night impeding our cell receptions in or out. The one place where we can: Facebook Hill, as it’s come to be known—a high ground where the media and legal teams are clustered.

On the frozen mornings, someone was already brewing or pressing coffee in our camp. My clan brother Kelvin, the owner of Yeego coffee, was always a welcomed sight. He provided us coffee while I was there.

It is coffee you need in times of revolution.

I deliberately did not go into the history and DAPL stuff for that is out there plenty.

In this continuing piece, I would like only to say that this was a transformative journey for me personally. I believe it was not my conscious choice, but the ancient spirit of our ancestors that touched me. Spontaneity and little doubt moved me on my first trip. It taught me that there are many places to take my heart with passion. This historic movement and place was it. My own heartbreak and weakness were not diminished but relocated to a place of peace. In my own experience, I yearned for a world of one-heartedness, sort of like this camp. These trips opened chambers of my spirit’s heart that I was distracted from. I said yes to strength, to worthiness and especially to love.

To be continued …