In the Diné world, this is the season of ceremonies, the time when the clans come together to heal collectively through summer N’daa ceremonies. N’daa, also called Enemy Way Ceremonies, is performed exclusively in the warmer seasons. Their announcement marks the first moaning of early summer thunder and the first lightning to the very first chill of fall.

In the Diné world, this is the season of ceremonies, the time when the clans come together to heal collectively through summer N’daa ceremonies. N’daa, also called Enemy Way Ceremonies, is performed exclusively in the warmer seasons. Their announcement marks the first moaning of early summer thunder and the first lightning to the very first chill of fall.

In this span of time, I remember it as being a social time for us kids and our elders. I remember excitement in sheep camps as the elders made plans to attend the upcoming healing ceremony for a related clan. There are talks of who will attend and who will stay and tend to the sheep and the cornfield. What our contribution will be. Corn mutton and strong voices carry the songs all night.

The distant clan is named as a patient in the ceremony and the meeting was held to plan this labor-intensive event. A member of our clan is also a patient, a Todichiini’ (Bitterwater) Clan, so we have a responsibility to help assist. Some uninformed still refer to it as a “squaw dance.” We never do, as squaw is a derogatory word. N’daa ceremonies are a healing and calming of the dragons within our psyche. Long ago, it was known as an Enemy Way Ceremony, but it was not for preparations for battles, nor enemies. Rather, it was a way of ridding the “alien” contact resulting in spiritual and physical injuries. This could be in the form of traumas of having been far removed from the center of the four sacred mountains that border our holy land. Many “injuries” are to bring the mind back into the circle of recognition by the Holy People. That is our constant and daily struggle.

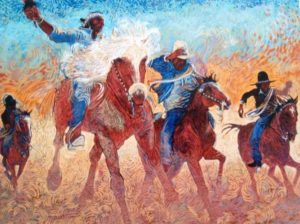

The patient named is RedHorse, the elder Hataali’ (Chanter), residing in the north below Navajo Mountain. The cast of characters in the communal headings are chosen from another separate clan, Ashii’hi (Salt), and in this case, “Joe Etsitty,” a shepherd and a farmer. Joe will be given the task of being initiated to that level of sacred responsibility. He will be the Aghaal (Rattle Wand), carrier to the patient’s home on horseback in a dramatic fashion with many riders accompanying him. After much chanting and prayers in the preparation of the wand, which is one foot long and adorned with snakeweed, yucca spines and various plants, in addition to many blessings, it is ready for its journey. The carrier is himself blessed and empowered by the transition of that power. With songs, they ride out, the wand held aloft and pounding of hooves across the valley.

Many of the Ashii’hi Clan members opt to drive out to the patient’s home, trucks and saddle decorated in a bright bundle of yarns which will be claimed immediately by the patient’s clan members once the horses arrive at the healing hoghaan. This hoghaan is a male hoghaan for its simple tipi-like shape made of logs and earth. Laughter and voices rises from the healing site as my maternal clan mothers and helpers prepare food to feed the multitude that is expected to attend. One’s presence in good faith and intent adds to and fuels that complete rejuvenation of the ailing person.

I am in a community of other kids I haven’t seen all year. The laughter and playtime is best at N’daa because the adults are all in a reverent mood and the aroma of delicious food wafts over the kitchen arbor where aproned ladies shout out instructions and helpers prepare the serving of food: mutton in various forms and thick tortilla wasted down with cowboy coffee, tea and sodas. Kneel down bread and roast corn, squash, beans and melons. Kneel down bread, so named because one can only make it kneeling down, includes ears of fresh milky corn grounded and made into batter, which is then placed in its own green and fresh leafs, folded, tied and baked.

I see my little buddies, chizzhy (parched) faced and dressed in their finest worn clothing dodge in and out between parked trucks and wagons playing cowboys and outlaws. Sheepdogs keep their respectful distance. Freshly ridden horses are tied to posts and fed, tails fending off flies. Inside the ceremonial hoghaan, faint voices sing symphonies of ancient chants that rise and fall as we can only hear from outside. We were too young and innocent to partake in that.

Later, after meals are consumed, the patient’s clan members gather in a wide circle down at the dance grounds where barrels of water and logs for bonfires are placed. As the evening arrives and the prescribed songs are sung, the social part of the ceremony begins. Fires are lit and voices and embers rise into the constellations. Snack booths are set up on the periphery of the dance circle. The dances commence and guys come with pocket change and bills to pay their dance partners. Young ladies with much dance energy can make a good amount of money on this night.

All night, the strong voices of singers from different clans try to outlast the other. I usually fall asleep right about then in a wagon bed. As the day breaks, the party returns to the hoghaan and more songs are sung outside the door to the east. The honored member of the Salt Clan gathers inside where gifts of softer goods and food will be tossed out through the smoke hole for the singers waiting outside. Boxes of cereals, candies and produce along with plastic utensils are flying out. There are squeals of excitement as folks grapple for gifts. It is a sight to behold.

I always felt renewed myself as a child witnessing generosity of wellness among my clans. Another night of dancing and chanting occurs at another site. The next morning, the other clan that received the gifting the morning prior reciprocates with gifting of their own—a three-day event that culminates in a rebalancing of someone from the clan, where all who attend are part of that healing process. It is a ceremony of giving, of generosity, and no one is turned away.

If you’re traveling through Diné land and see a fresh-boughed structure with many vehicles off the side of the road this time of the year, just know, you are witnessing N’daa. Send out good healing thoughts if you would. It is a healing for all.