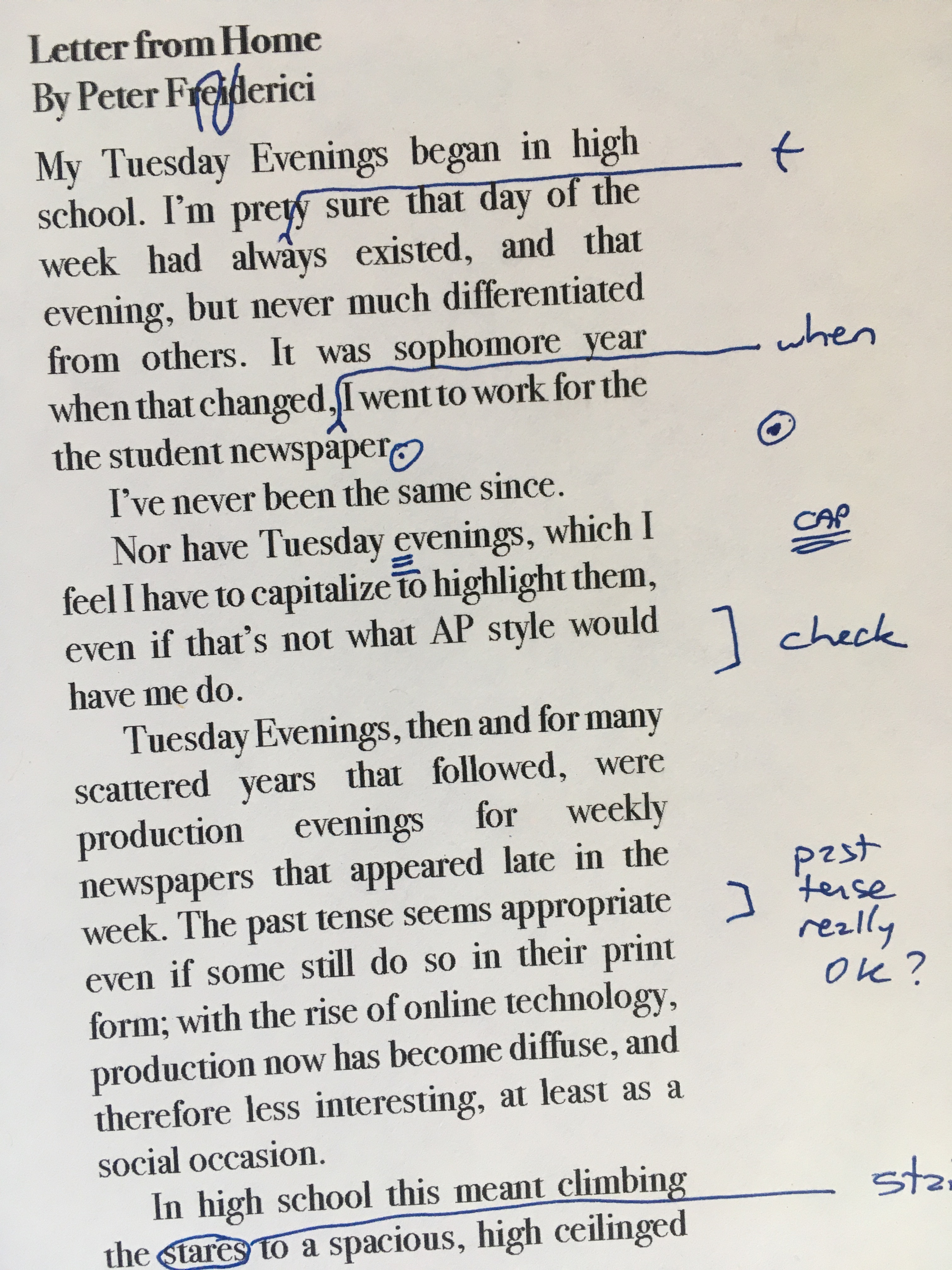

My Tuesday Evenings began in high school. I’m pretty sure that day of the week had always existed, and that evening, but never much differentiated from others. It was sophomore year when that changed, when I went to work for the student newspaper.

I’ve never been the same since.

Nor have Tuesday Evenings, which I feel I have to capitalize to highlight them, even if that’s not what AP style would have me do.

Tuesday Evenings, then and for many scattered years that followed, were production evenings for weekly newspapers that appeared late in the week. The past tense seems appropriate even if some still do so in their print form; with the rise of online technology, production now has become diffuse, and therefore less interesting, at least as a social occasion.

In high school Tuesday Evening meant climbing the stairs to a spacious, high-ceilinged room in the old part of the school and spending the late afternoon there, editing stories and laying out copy in straight columns on large sheets of card stock gridded with pale blue lines. We used translucent tape striped with differing widths of black lines to demarcate the columns or to box off the photos and ads. I loved the tactile nature of the work, the news and ideas and jokes coalescing first onto typewritten sheets and then typeset into narrow columns that relied on our steady hands to align them properly. Laid out that way, even the most sophomoric writing took on an air of authority that I’ve since never been able to shake.

As important, Tuesday Evenings meant taking a run to Nathan’s to pick up orders of cheese fries and shakes to bring back to what amounted to a clubhouse for the newspaper staff. For a shy kid in a big high school Tuesday Evenings were gold, shading imperceptibly from work to hanging out and friends and community, not that that’s a word I would have used at the time.

A few years later, my Tuesday Evenings had matured into full-blown Work, meaning a poorly paid but highly educational job at a free weekly in Chicago. Now the clubhouse was a sprawling second-floor suite on the gritty Near West Side, where some of the streets were wide enough to accommodate the turning semis that serviced the surrounding warehouses and manufacturing plants each morning. It was a rough-edged neighborhood, no glitz, where the meticulous squinting we proofreaders did for long hours seemed to echo the repetitive labor that went on all around us. It was detailed blue-pencil work, checking every hyphen and apostrophe, querying whether commas were used properly or names spelled correctly, looking up the proper names of theater groups and city streets in the ever-expanding style manual. When we were done with a page of corrections and an editor had checked them over the pages went straight to the compositors who set the type in the same room.

For lunch we’d walk over to a Greek diner for club sandwiches or, in season, a plate of fried smelt from Lake Michigan. The proofreaders were an eclectic if nerdy lot; there was the anthropology grad student who would likely never finish his dissertation; the film buff who seemed to spend almost every evening, except Tuesdays, in one of the city’s repertory houses; the expert Scrabble player, seemingly homeless, who frequently traveled with bags of paperback books that he somehow acquired and then sold back to secondhand bookstores in some kind of money-making feedback loop. The only woman in the group had a substance abuse problem and was somewhat less predictable in her habits than you’d expect of a professional proofreader.

I was the youngest of the lot and could make no claim to any sort of hardscrabble urban existence, as I was sharing a perfectly comfortable Wrigleyville apartment with a couple of high-school friends. Even though these Evenings began in the morning they really did extend into the true evening, sometimes very late, and I’d often find myself rattling home on the El at midnight, eyes glazed. But I loved the camaraderie of those long days, the shared appreciation of entertaining tidbits gleaned from the copy we read, the knowledge gleaned about obscure movies or theater performances, the jaded view that we as the most meticulous people in the building had of the writers as we learned which ones were lousy spellers, which ones were careful, which ones had their insightful but sloppily written work saved by an editor week after week.

By the time I got to my third stint of Tuesday Evenings the blue pencils had faded into posterity. Editors had the computing power to make their own corrections, and to lay everything out on a screen, but the drill remained largely the same. This was at the NAU Lumberjack, which even as it underwent a slow transition into a fully digital existence retained its once-a-week print production cycle. The student journalists ran the gamut from experienced almost-professionals to first-semester newbies just getting a taste of what extracurricular writing could be all about.

For me, the hard work lay in learning to be hands-off, to gently guide the editors into making their own conclusions about how to massage a lede or correct a faulty argument. I found I missed the narrow view I’d been able to afford as a beginner in Chicago, focusing for a half hour only on the intricacies of one story, not needing to keep the entire week’s issue in mind all at once, let alone think about assigning grades to student writers and editors with varying levels of commitment. And riding my bike home late through the darkened streets was not nearly as interesting as riding the midnight El.

But some of the late-night buzz was still there. After production wrapped on a couple of winter evenings I sat in the conference room with the couple of reporters, one of whom had made the discovery that one of the few remaining hostages being held by ISIS in Iraq was an NAU alumna. It was a secret known only to few, but we knew we had to research the story. And so in the quiet midnight room we outlined what we knew and what we wanted to learn, who we knew we could talk to and who we still had to find.

The story broke a few weeks later, when it was reported that the hostage, Kayla Mueller, had died in a bombing raid. That happened on a Friday, so the print production cycle was irrelevant. All day long a team of writers and editors worked to get out the first draft of her story, tightly focused on polishing, fact-checking, tightening the copy. When I got home that evening I broke down and cried, struck hard all of a sudden by what the news meant.

These days I teach on Tuesday evenings. It’s gratifying to coach the students on their writing, but it’s a regular class, not a production. The pressure’s off. And in media circles all around the world production has diffused into the very different time cycle of near-constant production. But I take comfort in knowing that in newsrooms and editing suites around the world eager lovers of words and of truth are working hard to ensure that they get it right, and on time. I guess you could say that it’s always Tuesday Evening somewhere.