This was my third Passover Seder/Shabbat observance. This year, I accompanied my girlfriend Tamar and my adopted son Daniel to this wonderful celebration of the shedding of the bondage of darkness in any form. It was the Navajo Moon of the Earth’s stirring. The moon was early full and all the hills, free of lights, showed its muted shine. The hills of the San Francisco Bay glittered and winked in allure.

This was my third Passover Seder/Shabbat observance. This year, I accompanied my girlfriend Tamar and my adopted son Daniel to this wonderful celebration of the shedding of the bondage of darkness in any form. It was the Navajo Moon of the Earth’s stirring. The moon was early full and all the hills, free of lights, showed its muted shine. The hills of the San Francisco Bay glittered and winked in allure.

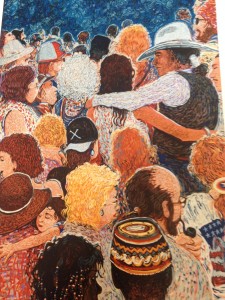

It was a fine night like many I’ve known where healing began. I came to be present and not just to eat. Many years ago, in Greenwich Village, I came late to a Seder, for I was held up by music on MacDougal Street. As my hand went to turn the knob of the apartment door, it was opened … for Elijah. On another fine night, in another kind of a canyon far away, a younger, hipper crowd gathered. A good mixture of Jewish friends and gentiles, officiated by a couple of youthful and energetic, thin young men. It was easy to laugh and muse on a tangent. It was a lighthearted crowd. We all felt loved and loving. I held my sweetheart closer.

The aroma of vegetarian food smelled like paradise must. Matzo bread, unleavened and hurried, made its way around as we all held onto freeing thoughts. The sustenance that ties us to our ancestors, made on the move. No time for culinary embellishments.

My ancestors were issued the very basic food staples to survive on. White flour and bacon tallow were provided, and when the coffee grounds were eaten raw it made people sick. Fry bread came from just such food conditions. This is the reason I rarely eat fry bread. It is not synonymous with our culture. It was another appropriation of the enemy’s culture.

The prayers of the stages of the ceremony were rendered accessible by a silly alligator song about loss, about redemption. Hang on to what matters to your hearts. This was about much more than celebrating the daunting task of freedom. It was about speaking to one another and having a conversation beyond the digital formats. It was about rising again without doubts, rising again from beneath the heavy blanket that binds our chains.

As I hear the stories and the songs, I am very much reminded of my own Dineh rituals of the seasonal changes and also the shaking off of the heaviness. This is the season for the stirring of the Earth: Chjee’n’daan. When the first game of Kesh Je’ was played and the night animals hurriedly hid their winnings from their day counterparts, the spoil was their chain. The animals of the daytime and the warming moons awoke to newness. They were recharged and invigorated for another year. Just as we must synchronize with the changes, we must share our blessings, our victories and our freedom. Freedom within is where it matters most.

In the voices of these different companies I heard the tongues of my elders long passed. I heard the rhythm of letting go and inviting beauty (Hozho’) into our lives. I heard the chants of the all night singers, like echoes into heaven. I even thought I heard my uncle chuckle somewhere in the corner. The gentle words of grandparents are what I heard. In the Beauty Way ceremony, it is what our souls need that is stated. It is in the beautiful soaring songs of this we find renewal again and again. When I was young, the medicine man/singer would arrive at our sheep camp. He was a priest, a rabbi and a therapist all in one. He carried himself with distinction, as one who leads, who liberates and maintained Hozho’ (peace). He would settle himself in at the western side of the hogan with reverence, the hogan that had been prepared with all the sacraments, rugs and sheepskins in the order of their presentation. I remember it as a solemn and whispered occasion.

The sound of the chanters clearing their throats marked the beginning of another section of the ceremony that required our attention and participation. Just as the Israelites were freed to flee into the desert for many years and the markings that allowed them such exodus, my Dineh ancestors had to negotiate hardships returning home from the brutal and unjust imprisonment at Fort Sumner, N.M. (Bosque Redondo). They traveled from the banks of the Pecos River onto the most desolate thorn-infested landscape. Their journey was from the sounds of the morning taps and marching boots, to the songs of mourning doves and early prayers of hope and freedom. Their stories of the journeys back to the center of the Four Sacred Mountains were just as frightful and filled with tests of faith. These were the visions I kept conjuring up in my mind during the celebration of that unshackling from darkness. Unlike the Seder, in our celebration of freedom and the consequent changes forced upon us, we do not have much to be cheerful about in our own rituals.

We were not even allowed to utter the name “Hweel de’” (Bosque Redondo) as young children. The elders frowned at our mentioning the painful place in any form. We knew stories from the elders and we knew of the hardship of the great and painful forced Long Walk that covered nearly 400 miles under the most unfriendly conditions.

The marchers were diverted to towns where they were mocked and abused by settlers who thought us to be an impediment to the progression of the westward movement. My ancestors were then made to build their own prison. The soldiers and their families lived in a degree of comfort in the buildings while the prisoners were on the outside huddled in holes dug by hand and covered only with bushes. They were treated as the lowest form of life. This was our Auschwitz, I suppose.

The Seder ceremony progressed, leading us closer to the food, the food that had been in preparation all day with the kitchen buzzing with the same feeling as the impending arrival of the medicine man for a three day healing and blessing ceremony. I felt there to be a plethora of issues I needed to unchain myself from, such as my floundering in complacency in my own small town success and my need to make another giant leap of faith. I sought freedom for growth, for challenges and especially for love. I felt the chain of being in extreme need and desire of intimacy. I felt the pull of the chains of social addiction and anger engendered by boarding school experiences and being part of a proud but beaten down people. Those links of bondage I saw morphing into gentle butterflies, calming and coloring my landscape and life.

This night I reconnected on that deeper level with my own people’s history. This night, I found release from much that was allowed to live within me still from the great Dineh Hero twin stories.

I wish for us all, a time of letting go of that which holds us back—a time to embrace that which challenges us and make us more loving, beautiful people. Axhee’he.