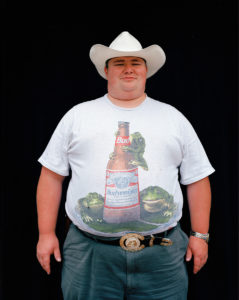

Portrait of Peter in Budweiser shirt as part of my series of portraits studying the sub-culture of cowboy in the former East of Germany. Photo © Eric O’Connell

I never thought speaking German would come in handy in the Southwest. Wouldn’t learning Spanish have been more useful? But I’d been in Arizona only a couple of years when I found out about an intriguing job: drive vanloads of German-speaking tourists around the Southwest, guiding them on hikes in the national parks.

I signed on at once. It was far better than working in an office. And I took a perverse pleasure in trying to figure out how to convey a sentence such as “Eons of uplift, with most of the rock layers staying more or less horizontal, resulted in the amazing geology of the Grand Staircase” in understandable German.

Fortunately, most of their questions were about people, anyway. We’d drive east from Vegas, stopping in St. George, Utah, for lunch, and everyone wanted to know about the Mormons. Did some of them still take multiple wives? And what about the ranchers? Everybody was fascinated by ranchers. How far did their cattle roam? How did they keep track of them? Who owned the land, anyway?

It’s no wonder they were fascinated by the expanse of the West. Most of the tour company customers were from the former East Germany and were accustomed to a society of severe constraints. They’d never learned much English, as Russian was their second language in school. That’s why they’d signed on to be led around in German. Mostly they were in their 50s and 60s, but fit, eager to hike every day. That was the itinerary: drive, hike, drive, hike. Zion, Bryce Canyon, the Escalante country, Capitol Reef, Canyonlands, Arches, Natural Bridges, Grand Canyon. For most of them this was likely to be a once-in-a-lifetime trip.

I loved the unexpected moments of cross-cultural consonance, or dissonance. Outside Boulder, Utah, we took what was always a hot hike into Lower Calf Creek Falls on the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. I hiked in shorts so that I could easily plunge into the frigid pool at the base of the falls. Afterwards someone would inevitably warn me that it was bad for my health to hike in wet bathing trunks—a strongly ingrained belief in Germany, but one that I thought didn’t translate well to the hot Southwest. In the baking August heat we’d all be dry in five minutes anyway.

In the tiny hamlet of Antimony, Utah, we stayed at a guest ranch whose owners turned out to have an affection for the odd German fascination with cowboy and Indian life: they had a giant panel of photos showing how they’d been to a powwow in Germany where pale-skinned men, and some women, dressed up in buckskin or loincloths, living out their ersatz dreams of the American West for a weekend.

It’s no wonder. Germany is a comfortable place with a high standard of living and a tradition of looking after one another—the kind of sociopolitical setting that some here would disdainfully call socialist. What that means in daily practice, over there, is that people worry less about whether they’ll have health care. They worry less about violent crime. New parents know they’ll have maternity leave. All of which makes it a very livable country.

But what Germans don’t have is open space. When we got to live in the urban warren of Hamburg for a spell a few years ago, in the flatlands of northern Germany, we found ourselves ever gravitating toward the banks of the Elbe River, where we could at least see for a distance of a few miles over the harbor.

And so for me, driving the van on another hot afternoon, what I craved was the look of amazement that I knew I would see in the rear-view mirror as we crested yet another white slickrock dome on the Devil’s Backbone, or commenced a long straightaway through the piñon-juniper country under the Bear’s Ears, or climbed up from the San Juan River to see the buttes of Monument Valley rising from a far horizon.

“So much space!” someone would say. Who lives there? they wanted to know. Who uses this land? Who owns it?

My job forced me to be a cross-cultural mediator who got to spend a lot of time thinking about the comparative virtues of place. And so at such moments it was hard not to feel a swelling of pride as I got to say, “For most of it, we all do. It’s public land. You can use it, but not own it.”

It made me think of some of the national leaders we look up to. President Franklin Roosevelt: “There is nothing so American as our national parks … The fundamental idea behind the parks … is that the country belongs to the people, that it is in process of making for the enrichment of the lives of all of us.”

Or the writer Wallace Stegner: “National parks are the best idea we ever had. Absolutely American, absolutely democratic, they reflect us at our best rather than our worst.”

It was a comforting notion that I always took with me as at the end of the two weeks I shepherded my new friends back to Vegas, where we immersed ourselves in the sensory overload of some casino buffet: the thought that the way in which we Americans have protected our public lands truly is America’s best idea. Or one of our two best ideas, anyway. What I learned from those German visitors is that the scenic lands we have set aside for protection are a treasure that belongs to the world—just as the ideal of America as a place where everybody has an equal place at the table can remain an inspiration for millions of people who will likely never set foot here.

Both of those American ideals are values that we need to fight for, generation after generation. Right now, it’s not too late to provide comments on the Drumpf administration’s plan to “review” national monument designations made by the previous three presidents. I did, remembering how those German travelers I got to know stepped onto their planes in Vegas, taking memories of our long horizons back home with them.