Follow me down a dirt road bordered by barbed wire fences under a 1950s blue sky. My feet are bare and I’m shirtless and I sing with great feeling, “Where have all the flowers gone long time passing? Where have all the flowers gone long time ago?” A deep ravine cuts across the widow Blanton’s pecan grove and goes under the farm road by our mailbox. In the cool shade of a giant pecan tree, dewberries blossom in a wild tangle. Here I sit and look at the mail and ponder the beautiful symmetry of the song and wonder about the emerging patterns in my own life.

Later I sit on the front porch of my home in the dark with my siblings and we chant, “Wimoweh, wimoweh, wimoweh, wimoweh,” and I get a tingle up my spine when brother Tommy breaks into a falsetto, “In the jungle, the mighty jungle the lion sleeps tonight.”

If I Had a Hammer would make sense to any son of Henry Brantley Norris, who apprenticed to a blacksmith at the age of 12. I had a hammer. And I had a song. I delivered the Old Testament poetry of Turn Turn Turn as I rode in the back of Daddy’s pickup truck; my voice rose and mixed with the limestone dust that boiled up from the ranch roads. Pete Seeger’s lyrics were informing my life although I was learning them from other artists.

Pete was at the height of his professional career touring with the Weavers. They had number one hits with songs like Goodnight Irene, Tzena Tzena and Kisses Sweeter than Wine when Pete was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee. When he was asked when and where he had performed his songs he replied, “I am not going to answer any questions as to my association, my philosophical or religious beliefs, or how I voted in any election, or any of these private affairs. I think these are very improper questions for any American to be asked, especially under such compulsion as this. I would be glad to tell you my life if you want to hear of it. I love my country very deeply.”

He was banned from TV and radio and blacklisted for the next 17 years. He and his wife Toshi lived in the log cabin they had built together and he was forced to take bookings in small coffee houses and colleges to support his family. His songs were recorded and made popular by Peter Paul and Mary, the Kingston Trio and Judy Collins. The ’60s were times of social turmoil—civil rights were being hotly debated and the Vietnam War was finding less support at home. Pete’s songs provided a vocabulary for protest. Each time he put a new head on his banjo he would ink in the words “This machine surrounds hate and forces it to surrender.” I found myself looking for political and social solutions in communal living.

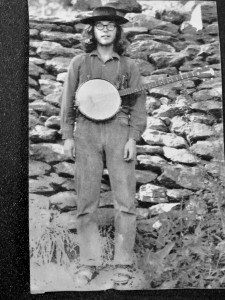

While living on the commune, I began learning to play the banjo. I mastered “Old Joe Clark” and “June Apple.” Late one night, Larry came up the stairs of the mill building and stuck his head into my tiny room. He was seriously freaked out. “Tony, there’s a bunch of drunk truck drivers downstairs looking for hippie chicks. Bring your banjo down and see if you can defuse the situation.” Tim was standing at the head of the stairs holding a hatchet. He assured me no one would get by him.

In the living room I found Larry and George playing reluctant host to four surly men in feed caps with bottles of Rolling Rock in their hands. The largest man sported a beard. He thrust a meaty hand in my face and said with thinly veiled threat, “I’m Big Possum. And this …”

He leaned forward and snagged the neck of his 3XL T-shirt with a finger as thick as a polish sausage. He tugged it down. He hit me with a blast of beery breath, “… is Little Possum.”

Clinging to his black curly chest hair was a tiny gray and pink baby possum.

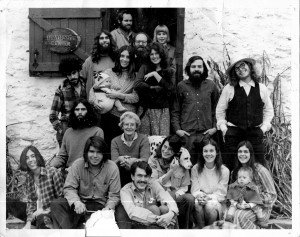

George had ridden his Harley to the Maryland Line Bar earlier to have a beer, and had gotten friendly with these truckers. When they asked about the commune he had made it sound like a Muslim terrorist’s heaven filled with willing virgin hippie chicks. George invited them to drop by. What George didn’t know was the invitation was being extended by CB radio up and down Interstate 83. Soon a convoy of semis was snaking down the ever-narrowing Heathcote Lane that terminated at the 1845 mill building that served as our common house. The first big rig that tried to negotiate the 90 degree turn across a low bridge spanning the creek became hopelessly stuck. Idling diesels were backed up the lane all the way to the county road.

I was repeating my meager repertoire. The swelling ranks of angry truckers did not want coffee and agreed they had heard enough banjo. They began to wander off in the dark in search of women. When a bold trucker tried to enter a tent in the lower meadow the occupants jumped in their VW Bus and drove into the neighbor’s yard honking their horn and flashing the cars lights. The sheriff was called and a wrecker was dispatched. It was morning before the last semi turned around in the lower meadow and exited Heathcote Valley.

I once heard Seeger quoted as saying, “The guitar is mightier than the bomb.” That day I hung up my banjo and decided to focus on playing the guitar.

Today I’m grateful for the wisdom of Pete Seeger. Sing about big things. Invite your audience to sing with you. One person can make a difference. Encourage every man to find his own voice—literally and figuratively—and speak out with confidence. Thanks Pete.