As late summer’s warmth relents to the early chills of autumn, I am reminded of how these changes affected my observation from the threshold of my mother’s hearth and home.

As late summer’s warmth relents to the early chills of autumn, I am reminded of how these changes affected my observation from the threshold of my mother’s hearth and home.

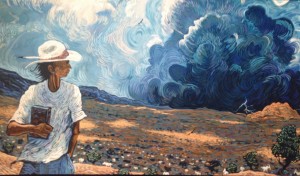

From a very young age, when I first learned of the cycle of seasons, I learned to gauge those stages in the changes of the Earth’s tone. Before and aside from the intrusion of U.S. government schools, it was the subtle signs I witnessed: the lowering heads of sunflowers as if in sadness; the cries of migratory birds far above my sheep trails as they traveled south; the sounds of drying cornhusks and lowered voices of my elders; the high-cooling clouds above the remnants of the last thunderheads and how the vibrant colors of the land slowly gave way to the muted carpet of tumbleweeds and rabbitbrush, scrub oaks and aspens clinging to their colors in vermillion and gold. This was the time of newness, our New Year.

In the chill of the Hunter Moon, we began our New Year, ghaaji’ (the spine; a new strength to carry another year). The last echoes of the summer N’daa (Enemy Way) ceremony songs are placed to memory as its season ends. The lonely chimes of sheep bells is the only sound I heard as I trailed the flock toward home knowing soon that the early flurry of snow would dust the land. We were headed into a time of lengthening nights and the slight shifting of constellations. Relegated to the duty of a shepherd, my brothers and father honed their axes with serious wood-hauling chores on hand. Our root cellar filled with melons, squash and corn recently harvested. Sentiment deeper than aloneness tendered my heart. It is a time of seasonal changes within as well.

In the course of a year, we moved with each season from one sheep camp to another to accommodate the weather and our farming and grazing rotations. On the southern slope of the limestone-capped mesa to the west is our winter home; the season of my birth, the air scented by cliff roses, binni’na’ (slope on mesa). At the foot of this mesa were our spring and autumn homes, and our main home. Pinyon and juniper filled the shallow canyons and arroyos. Big sagebrush plants carpeted the land. It always seemed as if water pockets reflected turquoise sky—tsa’t,aa (among sage) is its place name. Summertime found us at dzi’ghaii’ (valley free of trees), where our harvest was bountiful. On the alluvial plain of Black Mesa, summer heat awakened wandering dust devils. Each move was prompted by the season changes in the air. Cries of pinyon jays marked the closing of another harvest year. The seasonal moving always brought excitement to the camp as chickens were caught and the cats bagged alongside supplies for the next camp. My burro loaded with goat pelts, two miles of wagon trail is a gate to another season.

As we left fall into winter, stories were readied for long nights of Kesh’Je’ (Dineh Shoe Game) where we honored the animal kin hibernating for the season. We sang their songs and told their stories safely away from their presence, in a safe gambling game. From the first dustings of snow on the peaks and mesas, to the first audible thunder of spring, we mimicked their antics in stories and songs. The animals’ roles in our creation stories and the voices they so jealously guard echoed from many sheep camps of winter. It is said that the first game played on the edge of the Fourth World was won by the night animals, thus the nights are longer. Monsters and giants are always our adversaries in these dark and cold times. Songs are sung spirited and much laughter marks the mysteries of the long nights and shortening days.

The seasons within were honored as well. We celebrated stages of life rather than annual birthday markings. Aazh’chi’ (birth of a child), chi’deel dlo’ (first laugh) and kinaal’da’ (puberty), brings a child into fullness. This is the natural calendar we grew up with.

Later with the advent of Christianity and government teaching, we saw new rituals marking time: Aya’ na’haal yiz (Halloween), Taazhi’daa’ ghaal (Thanksgiving), Kesh mish, (Christmas), Ayee’zhi N’daa’hadlaa (Easter), and axhoo’haii’ (rodeos and other summer events).

There are practices in thoughts, words and actions we cannot perform out of their prescribed seasons. To do Kesh’Je’ in summer would be like Halloween being in May. Seasons hold their own sacredness and our communion with them as well. Now we prepare for winter by taking a snow bath in the first measurable depth. Now we prepare our voices and clear our conscience as we go into another season of Shoe Game, string games and dramas retold from the cusp of the Fourth World, our stage of creation.