It occurred to me when I saw the babushka tottering toward me on the sidewalk that she most likely did not understand the large English words on the front of her T-shirt: BLOW ME.

What I immediately wanted was to make eye contact with someone nearby, someone like-minded whose look would fleetingly telegraph they thought this as odd and destabilizing as I did. That did not happen. What I wanted next was to stare. That also did not happen.

Although she looked like a 70-something Kyrgyz grandmother, there is the possibility that the woman in the T-shirt was someone with a subversive sense of humor, a grasp of the dark art of American street slang and a nuanced understanding of the English language.

I don’t have much hard data to support my snap judgment, but I just don’t think that was the case.

We passed. Our eyes never met.

I walked on and remembered an incident from about 10 years ago. I was road tripping through the byways of Slovakia. I drove through a village and spotted a post office. I needed stamps for the postcards I was sending back home to make my friends envious of my world travels. Inside the post office was one clerk and a line of about six or seven people. I joined the queue.

A portable radio on the clerk’s desk was tuned to a station that was all over the map. A polka followed by some German heavy metal. Then a Slovak pop tune followed by an American rap song. As the lyrics of the rap song unspooled, I heard the singer outline his graphically explicit and highly bleepable menu of the night’s upcoming activities. You know George Carlin’s list of the seven words you can’t say on television? This song had all of those. Many many times.

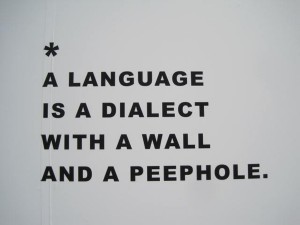

Some of the customers in line tapped their toes and bobbed their heads. I think I heard someone trying to hum along. As I listened to the lyrics, I was mortified. I’m certain I was the only one in the room who knew the meaning of the words, which made me cringe even further. I thought of what Edgar Allan Poe is supposed to have said: “Words have no power to impress the mind without the exquisite horror of their reality.”

In that post office and on the street with the babushka I felt startled by the language I have lovingly worked with for decades. I was uncomfortable with those familiar words in public, their radioactive power, their forbidden properties. I don’t consider myself a prude easily prone to offense and outrage. Would I have been uncomfortable had I heard or seen those words back in the States? I don’t think so, but here they took on weight and significance. They glowed in the dark, and it felt as if I were the only one who could see them.

Street life here in Bishkek has only a smattering of English. The occasional club or shop name (Obama Bar & Grill), graffiti spray-painted onto a building (Fight the Power) and a few restaurant menus (one with an entree called Fish on Royally, another called Male Whim). Some of the English is understandably mangled, which I find an unforgivable transgression in my own culture and a charming mishap in this one.

I’ve been living in Kyrgyzstan for six months. When I first arrived my central nervous system caffeinated with all the newness. I wearied from processing, cataloguing, translating. As this city and this culture have become more known, I’ve relaxed into hearing and seeing unfamiliar languages swirling around me. The words have glooped into a narcotizing sort of white noise. I hear pitch, rising and falling melodic lines, pauses and emphases. I just have little idea what anyone is talking about, and I’ve come to like it that way. I move through parts of my day in a blessed blur of unknowingness, feeling mildly sedated—until I slam into a language I know so well deployed without knowing its firepower.

I was walking home with a Russian friend a few nights ago after having a glass of wine in an outdoor pub. We passed a group of young men who were animated and laughing. Their conversation was like a small cloud around them: I knew it had form and shape, but I had no idea exactly what it was made of. When the young men had gone by, my friend turned to me and said: “Did you hear what that one guy was saying?”

I did hear him, but I had no idea what he said. And that made me glad.