![]() During the year of my birth Life magazine, at that time the carrier of the pulse of mainstream America, featured a ten-page spread on the fad of taking a 50-mile walk. The idea came from half-century-old executive order from President Teddy Roosevelt, no slouch himself when it came to physical fitness, who had mandated that officers in the Marines needed to be able to walk 50 miles in no more than 20 hours. When a military commander showed the historic document to his commander in chief, John F. Kennedy, the president wondered whether the Marines under his command could do it.

During the year of my birth Life magazine, at that time the carrier of the pulse of mainstream America, featured a ten-page spread on the fad of taking a 50-mile walk. The idea came from half-century-old executive order from President Teddy Roosevelt, no slouch himself when it came to physical fitness, who had mandated that officers in the Marines needed to be able to walk 50 miles in no more than 20 hours. When a military commander showed the historic document to his commander in chief, John F. Kennedy, the president wondered whether the Marines under his command could do it.

The result was some mixture of accomplishment and misery for a wide swath of Americans. According to Life and its extensive portfolio of black-and-white photos, the mixture included Marines and Air Force pilots who had no choice at all in the matter; stoic middle-aged members of a Minneapolis hiking club stalking through winter fields; 15 boys as young as 10 who did their half-century retracing a historic Revolutionary War route through snowy Indiana; a decorated general who’d been wounded with a severe leg injury in World War Two; and the president’s own kid brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, who was no doubt pleased, if a bit sore, to have demonstrated that the country’s Cold War dedication to physical fitness as an expression of the American Way of Life reached all the way up into the uppermost levels of the country’s administration.

What impresses me is that this range of citizens accomplished what they did in an era when hiking gear meant a metal canteen, stiff blister-inducing boots, and Spartan snack regimes that seemed to center largely on peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches. Not an energy gel packet in sight in those grainy photographs, nor anything resembling today’s running shoes or light hiking boots. The photographers didn’t shy away from showing the resulting blisters, or the immiserated faces.

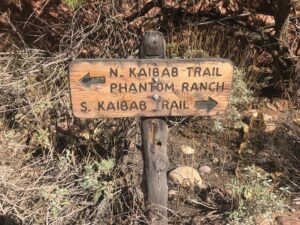

I think about those now-antique accomplishments every year when about this time I set off on an annual rim-to-rim Grand Canyon hike, accompanied by a friend or two and by many dozens, perhaps hundreds, of others who have adopted this peculiar task as a meaningful way to engage with an iconic landscape—and perhaps with one’s own abilities. If the enormity of the Grand Canyon is a great way to gain perspective on one’s own life and times, the fact that such a wide range of people once found meaning in taking a walk more than twice as long as a rim-to-rim crossing is a good reminder that ordinary people have always been capable of extraordinary things.

I think about those now-antique accomplishments every year when about this time I set off on an annual rim-to-rim Grand Canyon hike, accompanied by a friend or two and by many dozens, perhaps hundreds, of others who have adopted this peculiar task as a meaningful way to engage with an iconic landscape—and perhaps with one’s own abilities. If the enormity of the Grand Canyon is a great way to gain perspective on one’s own life and times, the fact that such a wide range of people once found meaning in taking a walk more than twice as long as a rim-to-rim crossing is a good reminder that ordinary people have always been capable of extraordinary things.

The late 1950s and early 1960s, as it happens, were also an era when rim-to-rim crossings became, if not commonplace, then at least a fairly standard undertaking in Grand Canyon. The main corridor trails were in fairly good shape by then, and road access to the rims was easy. Remarkably, some of the first efforts comprised small groups of students from the Arizona State School for the Deaf and Blind—blind hikers, guided by sighted ones, who made their way down and up the rugged trails by keeping a hand on the shoulder of the hiker in front of them.

According to newspaper accounts, it was a life-changing experience for some. “Boy, what an experience!,” said one of the hikers upon reaching the top. “We’ve sure got a lot to tell the fellows when we get back.” And I’m sure they did. It’s a humbling realization to think that a landscape that most of us experience so thoroughly through the eyes can leave such lasting imprints in the memories of those who can’t see at all—a reminder that even a landscape as thoroughly iconized and Instagrammed as the Grand Canyon has new things to teach us.

And it’s a reminder, too, that a good walk is an act of the imagination as much as it is of the body. “Exploring the world is one of the best ways of exploring the mind, and walking travels both terrains,” is how the essayist Rebecca Solnit put it in her book Wanderlust. Maybe it’s because I’m a writer that I see a natural affinity between taking a long walk and writing an essay—or constructing a story of any sort about how I experience life. I don’t know what it’s like writing a haiku, or a Hallmark card, or any other short and pithy exploration of life that wraps up soon, like a stroll around the block. What I do know is the analogy between setting out on a walk and not knowing what exactly I’ll find, and setting out to write an essay, or a book, with that same exploratory sense. As relieved as I am to get to the ending, it’s the getting there that really counts.

At the North Rim, last weekend, my friend and I finished our hike at sunset with no one else around—unusual in these days when so many hikers crowd the trails. We’d been crunching over snow in the final stretches, and the wind was cold. End of the season, is what I heard it insisting. What’s the next good walk, is what I wondered.