“Jan 4th snowing Today and Cold. 3 days work with team.”

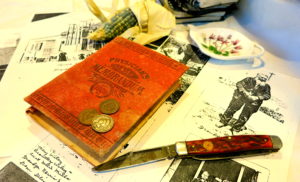

I have been reading my grandfather Henry New Year’s pocket calendar. It is about 4 inches by 6 inches and bound in red cloth. The cover reads Physician’s Memorandum for 1906, but grandpa’s entries span the following 20 years. The book is filled with testimonials for Gudes Pepto-Mangan, a patent medicine with miraculous properties and my grandpa’s penciled entries. Most of the entries deal with farm business. His spelling was variable—ears of corn became a drawled “years of corn.” His punctuation and capitalization were fluid and random. Lists include purchases of farm supplies and groceries: “2 sacks corn, 2 bushels oats, 60 years corn, 2 bushels cottonseed, sugar 50, cocoanut 10, potatoes 3, coloil 15, gal syrup 50, 2 cans tomatoes.”

The pale, silvery pencil lines tell the story of a lone farmer raising crops of cotton, corn and mixed vegetables in the sandy fields of North Central Texas. It’s easy for me to picture him going about his work. Fifty years later, and only a few miles distant, I walked barefoot behind the plow dropping corn or potatoes in the furrow. I chopped Johnson grass and irrigated melons and cantaloupes. My grandpa passed away 22 years before I was born. I learned about him from my father’s stories. When I was free from chores I explored a countryside grandpa first came to in the years before the Civil War, when the Comanches still ruled supreme. Decades separated me from his activities, but I felt kinship following in his steps.

The woods always waited at the edge of my childhood. The cool shadows of the white oak shade invited me from across the rusty barbed wire fence and the screen of horseweed that bordered the bean field. The woods—they promised endless adventure and mystery to me. Before I was old enough to ride the big yellow bus to school with my siblings, I could identify a dozen trees by their leaves in summer and during the winter by their bark and their silhouettes against the pale skies. My brother Sam taught me the names of the flowers that punctuated the woodlands and prairies. Sky blue Virginia dayflower, bluebonnets and the white froth of yarrow welcomed me when I took walks. I followed waterways and cattle trails deep into the unknown and searched for animal tracks in the mud of stock tanks and windmills. Spring nights were filled with the cries of the whip-poor-wills. I recall being terrified of the echoing reedy notes till Mama described the plump whiskered bird that made the sound and pointed out the answering call of its mate. Once I found the nest of a whip-poor-will on the forest floor, two large speckled eggs in a depression in the dead oak leaves. They looked so naked and vulnerable.

It was my brother Sam who introduced me to U.S. topographic maps. First, he showed me the tiny black rectangle that represented the old stone school house we lived in, sandwiched between the Methodist church and the cemetery. With his finger, he traced the route across open white patches that represented the fields where we grew watermelon, cantaloupe and tomatoes to a small circle of jagged concentric lines that designated the limestone hill that was the high point in the area. He pointed out the broken blue lines that revealed a seasonal water flow from a canyon labeled “Cason Hollow,” and he explained that a murderer had been cornered and captured there by the law. The murderer lent his name to the place. “He was the last man hanged in Parker County, Texas,” Sam said.

I remembered Sam’s reference to Cason years later when another brother mentioned in passing that Uncle Zeddie, my father’s younger brother had been born a twin. They were named Eddie Z and Zeddie E. When the twins were only a few days old, Eddie Z suddenly sickened. No-one knew where Grandpa Henry New Year was and by the time he was located, Eddie Z had died. Grandpa said he had been at what turned out to be the last hanging in Parker County.

A half century after my brother’s remarks, I searched the Internet and read in The Wichita Daily Times dated April 4, 1908 that James B. Cason was 34 when he murdered Jeff McLemore in the Eddelman pasture near Weatherford, Texas in February of 1907. He took McLemore’s money and team and fled after trying to disguise the body by setting fire to it. He was apprehended by lawmen and stood trial on April 2, 1908. He was convicted of murder. “The judge’s voice trembled” as he sentenced Cason to hang six weeks hence.

Grandpa may well have had the little red volume in his pocket at the hanging. I look at an entry that was inscribed one year later: “Jersey found her Calf march 3rd 1909. sold to Law & Lassiter 4 lbs butter 80c, Mrs McConel milk 5c. Pearl 1 milk 15 cts, eggs 25.”

The sale of milk and butter was essential to the financial success of his farm and to his family’s food supply, so this was celebratory news. I try to project myself into this moment. I wonder if he was pondering the cycle of life as he watched the cow cleaning her shiny calf. Was he remembering the death of his child the previous year? Did he superimpose images of a hanging man’s desperate struggles over that of the tiny still body of Eddie Z? Was he comforted that he still had a surviving kicking, crying infant?

“moved to the ingram place feb 8. Beans, Beets, Squash, Cucumber, Fatmeat”

I place the little red book on the shelf by 25 years’ worth of my Week-At-Glance pocket calendars. I wonder if any descendant of mine will ever search them for clues to a family mystery.