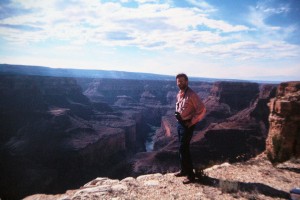

Somewhere on the Marble Canyon rim, late1990s. Photo courtesy of the author.

This week’s guest columnist is Peter Friederici.

When I first moved to Arizona I vowed I would practice restraint.

I won’t go there, I thought. Everyone does; it’s too easy, too obvious. Besides, there were any number of other canyons and peaks and desert vistas and high-mountain vales to explore, many of them spectacular, full of adventure, grand-ish.

But like so many other vows of celibacy mine was too easily broken.

In my case the lure was a base one: simple finances. As a struggling freelance journalist new to the state I was in no position to refuse when an old friend offered me a gig guiding a group of foreign parks managers around the Southwest.

And so there I stood at Mather Point one cool winter sunset, pointing out my recently acquired knowledge about the Cambrian and the Precambrian, the Colorado River and differential rates of erosion, to a dozen visitors who scarcely seemed to care what I had to say so busy were they oohing and ahhing like rank tourists rather than the professionals they were.

Like people who had traveled half a world to get there and would probably never be able to return.

Busy with the effort of acting like an old pro, I envied them their enthusiasm, their ability to be so easily moved by the mystery the canyon represented.

But after that I was free to fall in love quickly and thoroughly. I butt-slipped down the North Bass Trail from the old cabin, tilted down the East Rim from Saddle Mountain, suffered my hardest hike ever dragging myself up the Tanner one scorching summer day. And always I marked time and progress with glances up at the rim or down at the river, running blue-green or muddy brown depending on the season and the weather.

Before too long I got to know more about it than I wanted, learned that its fish were on the verge of blinking out, that the plants on its crowded banks were invasive tamarisk and camelweed.

I read John Wesley Powell and envied the embrace of mystery that he recounted:

August 13—We are now ready to start on our way down the Great Unknown … We have an unknown distance yet to run, an unknown river to explore. What falls there are, we know not; what rocks beset the channel, we know not; what walls rise over the river, we know not. Ah, well! We may conjecture many things … With some eagerness and some anxiety and some misgiving we enter the canyon below …

I wanted to find that same mystery in place that he did. Even as I loved hiking and exploring the place, I never quite could—the canyon could be dangerous, sure, but it was too thoroughly mapped and measured and explained, too altered by dams and overflights and human incursions of all sorts to feel truly wild. Its unknowns remained lower case, somewhere short of great.

Then came the new millennium and a wave of drought and a raft of studies that all predicted that the Colorado River, and the Southwest, are facing a new realm of aridity. Lake Powell? Not so much—welcome back, Glen Canyon. The cotton and alfalfa fields of the Sonoran Desert, the sprawling exurbs of Phoenix? An uncertain future at best. Lettuce in Yuma? Perhaps not a growth industry anymore. The computer models and the sheer observations are striking a common chord, suggesting that the Southwest is entering a new sort of normal, or perhaps a time when nothing is normal. And it is of course not the only such place. Higher temperatures, less water available in the dry places and often too much in the wet, bigger storms, higher sea levels—all the evidence points to a time when we all will be facing a whole new level of uncertainty.

It’s terrible news. It’s what a lack of restraint brings—at least when you multiply lack of restraint by all the billions of people using the Earth’s fossil fuels. As you know if you’ve followed the public debate in this country, or the run-up to the Paris climate talks in general, societies have not done a stellar job of organizing themselves to avert these particular uncertainties in our future.

So now, when I go take a look at the Colorado, I am increasingly moved by a curious new thought, namely that the future we face in the Southwest is becoming just as mysterious, as awe-ful and shuddering as what Powell faced.

Yes, some of Powell’s crew didn’t make it out alive, and we will no doubt lose many things dear to us as we move into our shared future. It is a Great Unknown after all. What do we do about it? We do everything: work on the problem, batten down the hatches, tighten the straps on the life preservers, and yes, feel an eagerness to be moving down the surging current we can’t ever fully understand.

Peter Friederici is a writer and a former itinerant field biologist and tour guide. He teaches journalism at Northern Arizona University in between bouts of camping, gardening, and fixing up an old house.