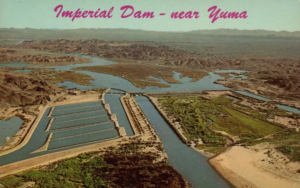

I well remember standing down at Imperial Dam all those years ago, a budding journalist, and thinking: this is going to be interesting. I meant Arizona. I meant the Southwest. I meant me, in the Southwest.

I well remember standing down at Imperial Dam all those years ago, a budding journalist, and thinking: this is going to be interesting. I meant Arizona. I meant the Southwest. I meant me, in the Southwest.

But deep down what I really meant was that I wanted to live in a story.

It was winter, and the camping was perfect. My friend Tim and I went for a fast run through the tumbled and bare Mordor hills near the Colorado. The marsh reeds spat out the ridiculous cacophonies of coots and grackles. It was pleasant to be living outdoors in February, to feel the warm sun. We were both from up north and not used to this feeling of bodies opening up in winter.

Near Mittry Lake we talked to an older man who helped operate Imperial Dam or, perhaps more precisely, the Colorado River itself. “Bureau of Reclamation—25 Years of Safe Driving” read his belt buckle. He was proud of his work, a matter of engineering maximum efficiency from a river that he labeled as “treacherous, deceiving.” The river was unreliable. Sometimes there was too little. Sometimes there was too much. Back in ’83 the river flooded to excess, leaving the Bureau with the unsavory need to let the surplus flow down to Mexico, unneeded, unwanted. But more often there was too little.

“If the water doesn’t show up here, it’s piss in your pants time,” he said.

The water was like oil greasing the immense machinery of modern America. From the dam it coursed, trimly organized in a smooth concrete canal, off to work in the Imperial Valley. Without it, the whole system would seize up, coughing out dust and laid-off workers. There wasn’t much room for error. He thought that before too long Santa Barbara, where there was both thirst and money, would be importing tankers full of fresh water from Alaska.

This was all fascinating to me, and not only because talking to him was like talking to a frontier pioneer in a modern age. Chicago had its problems, but a lack of water was not one of them. It was home but had for me already become more a place to be from than a place to be. It was too big, too gray, too surrounded by flat fields of drab crops. There wasn’t even a memory of mountains. Some of my friends from there had already lit out on the long trek to Seattle to start over. Here there were mountains, there was ocean and the energy of a city pulsing with young people. Nirvana! That was a good prospect for me, I knew. I’d be taken into the grungy Midwestern diaspora there. I remember sitting out at Gas Works Park one evening with some newly settled friends, overlooking the water of Puget Sound and the glittering skyline, and thinking, what about it? Could I make this place mine?

Maybe I could have. But the Southwest intervened like a potential lover coming on strong, the surreal blue slash of the clear lower Colorado against the burned-looking hills, the funny RV encampments hard by the river full of Midwestern refugees from an earlier generation, the fading glimmers of postwar Sunbelt optimism—malls, station wagons, air-conditioners—that I felt reverberating still on the streets of Tucson. It was compelling. It was sensual. It was . . . interesting.

But what sealed the deal was that the place was also on a trajectory that seemed as though it might lead away from the suburban comfort I was rebelling against. By then I’d already read one of the early books about global warming, by the climatologist Stephen Schneider. However taxed this weird blue and too-skinny river was already, it would become more so, and then what would become of the canals, the farms, the people? This is going to be interesting, I thought, and that was enough to swing me over the edge. It wouldn’t be too long before I loaded up my non-air-conditioned two-wheel-drive Ford Ranger, hitherto parked incongruously on a driveway in my parents’ chi-chi neighborhood, a place where pickups typically showed up only when some tradesmen or landscapers were working, and headed west. As I passed through the rolling plains of Texas and New Mexico, some loudmouth named Rush Limbaugh was fulminating against the Clinton administration. Out in the Pacific a series of El Niño-fed storms was taking aim at California and the Southwest. Soon there would be massive flooding all along the Gila River, and up on the Verde, and in a little city up north named Flagstaff. It would be interesting.

That was 25 years ago. El Niño still comes, but since then the flow of the Colorado has dropped by almost 20 percent annually, on average, and the big reservoirs, Powell and Mead, are half empty—or is it half full? But the system works, still, for now, and the farmworkers guide the irrigation water where it is wanted, and the crops grow, and the trucks move them off to the air-conditioned supermarkets, and a new generation of RVers camp out along the blue Colorado in the winter, and a new generation of young people from somewhere else are seduced by the mountains, by the desert basins, by the feeling of starting over. On Central Street in Phoenix, APS has just built a temporary ice-skating rink in an urban canyon to celebrate the cooler season; apparently the company had some money left over to pay for this after spending something like $30 million to defeat a renewable-energy initiative on the November ballot. And somewhere out in the placeless space of international bureaucracy a United Nations panel issued a report indicating how little time humanity has to radically reform economies and ways of living if we are to avert the worst effects of global warming.

The Southwest, so vulnerable in its water supplies, is on the front lines of the work to be done. But so, you could argue, is almost anyplace—the Southeast with its increased floods, the Midwest with its droughts, Western forests with their fires, pretty much anyplace along a seacoast. To say nothing of far more desperate places farther south, or on other continents.

May you live in interesting times. It’s said to be one of those ancient Chinese nuggets of wisdom of uncertain provenance. When I was in my 20s and looking for something new, it seemed a benediction. But these days it seems more a curse.