In winter I miss them. Without the windows and doors open I don’t come across them as often, those others who live where I live, the lively silent ones. I like finding ants, spiders, moths and other tiny beings on my windowsill, under the sink, outside the door and on the kitchen counter. I peer at them closely. I gather them onto paper or shoo them into a cup for a chat before setting them gently outside. They are the winged ones, the crusty shelled ones, the many legged ones. And they don’t talk a lot, and they don’t look preoccupied with smart phones. Just us here, they seem to say to me. There is nothing to do today but be.

It has not always been so, this tender leap of my heart I feel around the creepy crawlies. And it is not always so. One time I put my leg into my blue jeans after swimming in the Verde and about left my skin behind when the many feet of a huge centipede crawled up my thigh! And if I wake because tiny sharp feet under the sheets scratch at the back of my knee, I am not pleased. In the bathtub is my least favorite time to see ants exploring. But mostly I like a glimpse of delicate movement to catch my eye. I look at color or antennae and smile. Who are you? What’s on your plate today?

I know people who shriek when a spider yawns behind the tea canister on the counter. But I’ve never been a shrieking gal. Growing up in Arizona makes one careful about turning over rocks of course. And the outhouses I’ve lived with at fire lookouts taught me ease with spiders. Those wooden sheds hosted great masses of daddy longlegs quivering in a top corner. You learned to make your peace and do your business despite the company. Exhaustion can also make one patient with spiders. One time on fire crew we spent most of the night lining five acres on a rocky hillside in the Bradshaw Mountains. When the foreman finally said we could catch a couple of hours sleep, the only place to stretch out was in the dirt on the two-foot wide fire line. I was much too tired to care as the spiders fleeing the heat of the fire inside the line walked over my yellow fire shirt.

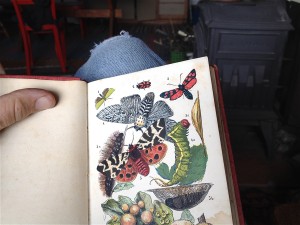

Tonight it is freezing outside as spring spits another round of snow. I sit by the Resolute woodstove in my rocking chair savoring the bugs on my lap. It’s a book I picked up at an antiquarian book fair in a hotel near Russell Square in London. At that browser’s paradise I saw precious tomes from several centuries, some worth thousands of dollars. But the sellers also had tables of bargains: books too tattered or soiled to bring a premium price. There I purchased an 1866 printing of The Common Objects of The Country by the Rev. J. G. Wood. It cost one shilling once upon a time. I paid 10 pounds for it—between $15 and $18—because I couldn’t resist the glowing pages of illustrations. Water stains make the book worthless to collectors, but for me the marks almost add to the depictions of beetles and caterpillars, as if the creatures are crawling out of a bog of a book. “With illustrations by Coleman, printed in colours by Evans” it says on the title page. When I did a bit of online searching, I discovered the printer, Evans, perfected a combination of etching and presswork that made him a famous man in English publishing in the mid-1800s. His attention to detail makes beetles and mushrooms and spores look so alive—I feel like they were scooped into the cage of the book a century ago and might crawl off my lap to get closer to the warmth of the stove if I look away too long. What fine company these creatures of English woods who enliven my winter night with delicate shapes of wing and leg poses. They are not asking to be pet, yet I put my hand down on their colors as if I might feel them squirm. I marvel at markings. I imagine burrows through dirt and nests on the undersides of leaves. I think of birds pouncing on them to gulp crunchy flavors. And I notice my thumb with its curve and wrinkles is beginning to look like a caterpillar. Maybe my aging is a kind of pupae stage and my fingers will turn into butterflies at the end of winter!

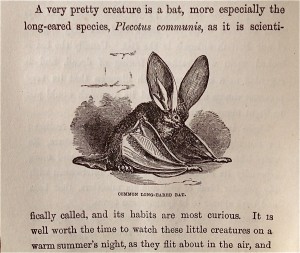

But what is this precious jackrabbit-like creature? I turn a page and a dab of illustration brings to me the common long-eared bat, looking bug-like in the lines of the etching by Evans. “When the bat is living, the ears are of singular beauty,” writes the reverend. “Their substance is delicate, and semi-transparent if viewed against the light; so much so, indeed, that by the aid of a microscope the circulation of the blood can be detected.” This report from a feast of looking closely pleases me. I think of the reverend fresh from the woods gently taking a breathing bat from his coat pocket to tuck its ear under a microscope. He marvels at the tiny rivers of blood pulsing there. To thank the bat for its patience, does he offer it a sip of his tea? Does the bat flutter back into the night to tell its fellows about the giant full moon of an eyeball it observed overhead? Ah, but they don’t talk, do they? No gossiping about wonders for them. I sigh inside the quiet I’ve chosen. Not common at all, these common objects of the country, I think. Uncommonly companionable, indeed. Perfect pals for flights of fancy through the brooding length of winter.

But what is this precious jackrabbit-like creature? I turn a page and a dab of illustration brings to me the common long-eared bat, looking bug-like in the lines of the etching by Evans. “When the bat is living, the ears are of singular beauty,” writes the reverend. “Their substance is delicate, and semi-transparent if viewed against the light; so much so, indeed, that by the aid of a microscope the circulation of the blood can be detected.” This report from a feast of looking closely pleases me. I think of the reverend fresh from the woods gently taking a breathing bat from his coat pocket to tuck its ear under a microscope. He marvels at the tiny rivers of blood pulsing there. To thank the bat for its patience, does he offer it a sip of his tea? Does the bat flutter back into the night to tell its fellows about the giant full moon of an eyeball it observed overhead? Ah, but they don’t talk, do they? No gossiping about wonders for them. I sigh inside the quiet I’ve chosen. Not common at all, these common objects of the country, I think. Uncommonly companionable, indeed. Perfect pals for flights of fancy through the brooding length of winter.