There wasn’t much selection among the postcards, and I picked a standard canyon scene, the rock walls and sloping scree slopes careening up high over the river and somehow all squeezed inadequately onto a four-by-six rectangle obviously far too small for the grandeur of the canyon but bigger than a standard postcard so that you had to fill up more space than you might have intended for a quick greeting. You also had to frank the thing with a Forever stamp—not a bad name here in a place where the trail crew members were out fixing divots in the trail caused by rocks 1.7 billion years old toppling down from the nearest of the cliffs.

There wasn’t much selection among the postcards, and I picked a standard canyon scene, the rock walls and sloping scree slopes careening up high over the river and somehow all squeezed inadequately onto a four-by-six rectangle obviously far too small for the grandeur of the canyon but bigger than a standard postcard so that you had to fill up more space than you might have intended for a quick greeting. You also had to frank the thing with a Forever stamp—not a bad name here in a place where the trail crew members were out fixing divots in the trail caused by rocks 1.7 billion years old toppling down from the nearest of the cliffs.

The cashier was only too happy to sell me one, perhaps because that was an easy task compared to the thankless and apparently impossible one of trying to shoehorn the names of a small party of hikers onto the crammed dinner reservation chart.

“So there’s nothing you can do?” the irritable hiker asked, a middle-aged woman with bobbed hair and a too-purposeful-for-vacation attitude.

“No,” the cashier finally concluded, setting the clipboard behind her as the woman turned away. Neither apologized.

So, I affixed the stamp on the postcard. The change went into the tip jar, labeled “Too heavy to carry out?” I wondered who does carry out the change—the canteen workers? Or do they let it accumulate into a bag that they relegate to the mule train? And I turned to my task, hoping that Mom in Chicago would live long enough to receive the card.

My sister had told me that she had stopped opening the mail herself. This was a big concession to age. For decades—probably since the kids left the house and left her with a less-structured schedule—the mail delivery had been a major punctuation in her day, a relief of the quotidian in the grumpy and difficult year between my dad’s diagnosis and his death, a workaday pause in the long years of her self-sufficient widowhood, and now in the last years a consistent reminder of her decline into being practically an invalid.

“Peter, is the mail here yet? Can you go look?” she’d ask, stooped and seated on the kitchen chair whenever we went to spend a week or two at her house—Christmas or summer vacation. The walker took her around the house pretty effectively, but the single step out the kitchen door and down to the mailbox on the stoop she could no longer manage.

“I’m so tired of all this,” she’d say as I brought the mail in. But at least the stack was a brief reprieve. Maybe a bill to pay, a report on her retirement savings, a fundraising pitch from an environmental group, a magazine (Smithsonian: like National Geographic for retirees). On good days, a postcard from a wandering grandchild, or a card from one of the relatives in Germany. On bad days, notice of the death of another far-flung friend who’d probably been younger than her. She was at the point of having outlived almost everyone else in her generation.

Her generation: astonishingly, she’d made the long drive out to the canyon for the first time in summer 1937, her immigrant father at the wheel of the Studebaker. She was 12 when she did the hike, spending a long day hiking down and back out with her father. At home she pasted a photo of what she’d experienced into an album that she turned in at school. There it is in stark black and white, the Black Bridge, almost brand new at that time, but looking pretty much identical to what I’d seen just before we got to Phantom: an unlikely straight slash in a place all curves and undulations, the smooth amid the rough, the sight of it from above always a relief that lets you know the steep drop of the Kaibab Trail is almost done.

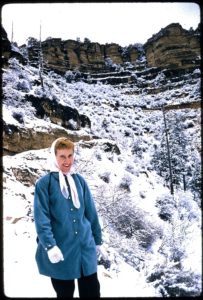

In those days there was scarcely a thought about carrying more than a canteen and a few salt tablets, nor of being rescued if you got into trouble. But they made it out, of course, as did she and my own father when the two of them hiked down during their honeymoon. By that time the family memories of her blossom into Kodachrome. There’s a lovely photo of her, looking radiant, striding down the Bright Angel Trail through the spring snow. They made it down as far as Plateau Point. If they had any of the supplies we these days consider mandatory—water bottle, snacks, another layer—she sure wasn’t carrying them. But it appears she didn’t forget her lipstick. It was a stroll in the park. That’s how it goes on a honeymoon.

For a lifelong Chicagoan she had a lifelong and, I would say, deep relationship with the place, her visits periodic accent marks emphasizing very different periods of her life. She was back again with one of my sisters and her first grandson not long after I moved to Flagstaff, still learning how to adapt to widowhood. And then again a few years later when it was time—finally, finally, I am sure she was thinking to herself—for me to get married. She wasn’t doing any more hiking then, but it was poignant to see her looking down from the rim at the Bright Angel, filled with memories of her previous trips there. For the last time.

All this was a lot to think about as I was writing the postcard, and we still had a long way to go that afternoon, so I had to wrap it up. I scribbled something about how being at Phantom Ranch made me think of her, and off we went, headed for the long grind up the North Kaibab.

I was glad she got the card, and that she lived long enough that I was able to see it at Christmas, stuck to her fridge with other mementoes of travels and children and grandchildren. I don’t know how much she thought of the place during that last month, when she was bedridden, when a walk on even flat terrain was no more but memory. But I do know that those long-ago visits live on in family memories, as part of the stories we tell ourselves about who we are. Letter from home? Letter to home? Sometimes it’s hard to tell the difference.