Because this year the full moon peaks in the wee hours of Christmas morning, I found myself imagining Santa straying in his rounds. I pictured him in a fit of lunacy landing on the top of the Weatherford Hotel to look for a pine cone, and then entranced by the vision of the big moon from the balcony of the Zane Grey, he wanders the streets seeking a gin and tonic and dancing and maybe a food truck. I picture the moon strutting her stuff so fully on Christmas Eve it inspires coyotes from hither and yon to howl Christmas carols across the landscape. Go ahead, imagine it: a jingling of bells meets a pack of furry heads tilted at the sky gargling “tarumpapumpum …”

Because this year the full moon peaks in the wee hours of Christmas morning, I found myself imagining Santa straying in his rounds. I pictured him in a fit of lunacy landing on the top of the Weatherford Hotel to look for a pine cone, and then entranced by the vision of the big moon from the balcony of the Zane Grey, he wanders the streets seeking a gin and tonic and dancing and maybe a food truck. I picture the moon strutting her stuff so fully on Christmas Eve it inspires coyotes from hither and yon to howl Christmas carols across the landscape. Go ahead, imagine it: a jingling of bells meets a pack of furry heads tilted at the sky gargling “tarumpapumpum …”

I think of music because the full moon feels to me like a big song in the sky: a giant chord of shadow and silhouette and silky light sounded, or trickling meditative notes played on a night-kissed guitar. This presence of music in my head might have started when we Brownie scouts sang, “I see the moon and the moon sees me, down through the leaves of the old oak tree.” Little girl voices quavered toward the big finish, “Please let the light that shines on me, shine on the one I love.” Earnest hearts trying to make LOVE the best note, the long note, the most hopeful note.

Later I’d read poetry by Carl Sandburg and think music again. He wrote, “Listen awhile, the moon is a lovely woman, a lonely woman, lost in a silver dress, lost in a circus rider’s silver dress.” Listen awhile, he said.

And listen I did when our high school hiking club camped by the Colorado River below Phantom Ranch. One of our gang insisted we get out of sleeping bags to walk out onto the suspension bridge. There we watched the spring full moon paint the cliffs before making her appearance in her silver dress. With the light, we were flooded by the sounds of the river’s crooning under our feet, the music of our teasing and laughter and finally the counterpoint of our awed silence on the walk back to tents in a flashlight-free sea of light.

About the time I saw Richard Shelton’s poem “5 Lies About the Moon” in The New Yorker—it begins, “She is a bald-headed woman”—I owned a letterpress and made a calendar of full moon dates to give to my hiking, camping and river-running friends each year. The calendar helped us seek moon company to light the way out of Havasu Canyon, and climb Piestewa Peak or Thumb Butte for moon rise with city lights, or get a bucket of chicken to eat in the bed of a truck out on A-1 Mountain Road. Sometimes I’d shiver solo with my thermos of Earl Grey between sunset and moonrise. Once in a little oak grove outside the cabin at Grandview Lookout I heard multiple wet snorts as I sipped tea and spotted a small herd of elk drifting through near shadows. The moon seemed to lift her head over the pine trees to join me in a closer look at big rumps, knobby knees and antlers.

Lately I’ve been seeing postcards with a super-sized full moon: a giant moon, a golden moon so large it dwarfs the silhouette of saguaro or mountain peak. I think the photographers with their Photoshop tricks have turned the moon permanently away from being a baldheaded woman back to being a shining circus rider.

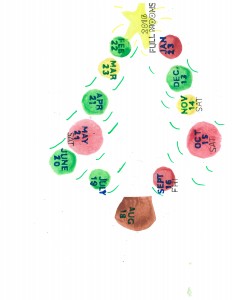

So be a poet or be a guide, or both. Here is next year’s full moons, my gift to you, dear readers, at this holiday time. I like to think putting this Christmas tree of dates on your refrigerator or in your glove box will nudge you to create for yourself at least five full moon walks in 2016. Go solo at least twice, will you, to listen closely to moon song. And invite trail handy friends a couple of times. And yes, at least once, be a moon guide, take someone unaccustomed to the outdoors for a dose of dusk to dark; it is a great gift to give another, that celestial music. A moon rise habit can become a lifelong present, the recurring gift of sharing powerful resonant presence.