When I was a little girl, my step-grandfather made my siblings and me small cedar chests with bronze hinges. I’ve kept mine. Ever since I left home for college, it’s moved with me. Inside are decades of concert ticket stubs (Violent Femmes, Blur, Morrissey), postcards from Wisconsin, Bali, France, notes from friends that date back to my junior year in high school, letters in great abundance.

When I was a little girl, my step-grandfather made my siblings and me small cedar chests with bronze hinges. I’ve kept mine. Ever since I left home for college, it’s moved with me. Inside are decades of concert ticket stubs (Violent Femmes, Blur, Morrissey), postcards from Wisconsin, Bali, France, notes from friends that date back to my junior year in high school, letters in great abundance.

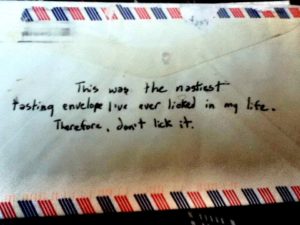

For as much as I love the immediacy of electronic communication, rummaging through the cedar chest makes me mournfully nostalgic for those handwritten letters—the effort and personality in the script. Someone put pen to paper, put the paper in an envelope, paid for a stamp and put the contents in an actual mailbox. There was a deliberate, meaningful process involved.

A letter was never truly thoughtless. You couldn’t “drunk send” a letter or “accidentally send” a letter or compose and send a letter in a blind rage. (I mean, you could, but no one I know ever did.) No letter was ever sent, erroneously, to dozens of unintended recipients.

When someone wrote me a letter, I always felt an urgent desire to write back, and while I do try to reply to all of my email, the urge isn’t always there; no email gives me a thrill, no email strums my heartstrings.

Frankly, replying to email usually feels like a perfunctory drag.

I didn’t use email until I was a freshman in college. That year, I also took a required humanities course. My professor was, give or take, the same age as I am now, and I found her utterly fascinating—insanely smart, well-traveled, multi-lingual, a woman who could talk about Heart of Darkness in a way that made me actually want to read the book.

Those days, if you wanted to communicate with your professor, you had to visit them during office hours, you had to talk to them in person. Those days, email was so new and infrequently used, your chances of getting a response from a professor would be better via a scroll-bearing raven than composing and sending an email.

Instead, one talked to their professors. Face to face. Often awkwardly. And I don’t remember why, but during one of my awkward face-to-face conversations with my crazy-smart, crazy-interesting professor, I told her I wrote poetry. In turn, she began inviting me to her office hours, not to talk coursework, but to help me grow my poems.

After graduation, I continued to send her poetry—now accompanied by letters detailing my rather mundane foray into adult life. She always wrote back.

When I got my first real apartment (with a dishwasher, a balcony, a proper living room), my former professor took the train from Kenosha to Chicago to visit for a weekend. We spent those days having what I considered “grown up” dinners and “grown up conversations”—we went to the Art Institute of Chicago and the Botanical Gardens where we sat on a bench and she gave me my first set of mala beads (that she had strung herself) and taught me how to meditate. I was 22. One of my role models, one of the women I most looked up to, chose to spend an entire weekend with me. I felt honored and, well, incredibly cool.

When email finally gained traction, letters were replaced by screen communique. My former professor’s emails were typically far more brief than her letters once were, but I understood why: emails, unlike letters, can be rattled off.

Nevertheless, even when it was email, she always wrote back.

When I moved to Milwaukee, in my early 30s, geographic proximity made up for the letter-writing-intimacy email had stolen—my former professor and I went to museums, performances given by her sister’s dance company, dinners downtown. We talked art, politics and books.

When I got cancer, we started talking personal life. Relationships. Bodies. Mortality. We spoke less through email, and often on the phone. When I went alone to my last chemotherapy infusion, I fell asleep (one of the less pernicious side-effects of chemo is sheer boredom) and woke to find my former professor sitting beside me, ready to take me out to lunch.

I dedicated my first book to my her, and rightly so.

These days, it feels strange to refer to her as my “former professor”—we’re genuinely close now—friends, confidants. We enjoy marathon phone calls every couple of months; when I’m in the Midwest, I make a point of staying an afternoon or evening with her; and yes, we email multiple times per week.

Students email me like I’m a doctor on call. I’ve had frantic 3-a.m. emails asking about an assignment that’s due at 8:45 a.m. I’ve had complaints that I don’t respond “fast enough.” I’ve had important communications go right to spam, never to be seen, until the subject of the email is broached in “real time.” I’m not one to pine for some imagined good old days, but email sometimes makes me pine for the them.

Only when they graduate do I give my students my “real” email address. (I also then allow them, if they desire, to friend me on Facebook and follow me on Instagram—such are the “privileges” of finishing high school.) Every once in a while a former student reaches out—as was the case several months ago when a former student emailed me asking if he could visit while on his spring break.

During my prep hour, he and I sat in an empty office. I drank my cup of coffee and picked at a donut from the copy room. What was intended to be a brief “how are you/how is college/how’s life” evolved into an 85-minute heart-to-heart in which I felt disarmed enough to share elements of my own story that I generally reserve for an inner circle of family and friends. I was surprised by who he had become.

We talked about life’s bumps and sheer cliffs, its meadows and clear seas. We talked about death and happiness, how you cope with the intractability of one, how you dig out and grasp the often ephemeral other.

I liked this young man when he was my student, but now I just plain enjoyed his company. He was charming, funny and kind.

The fact of the matter is no one writes letters anymore. Email is the new letter writing, however imperfect, however lacking. We’re inundated with email in a way we were never inundated with handwritten letters. Still, it’s important to write back. (I mean, use your discretion—maybe don’t write back to the mysterious Sudanese Prince who desperately needs your social security number.)

As I sat with my former student, connecting, I felt so grateful that he had sent me an email and that, despite my extreme email fatigue, I’d written back.