There wasn’t a good place to be in the days after the election. For someone who believes that the candidate we’ve just elected disqualified himself years ago when he forsook his oath to defend the Constitution by choosing to watch TV while his supporters ransacked the Capitol, there was no escaping a sickening feeling of doom, or a feeling of uncanniness that tens of millions of fellow citizens somehow felt OK enough about that option to fill in that particular bubble on their ballot. And even some people I know who did so admitted to dismay at how our political system had come to this.

There wasn’t a good place to be in the days after the election. For someone who believes that the candidate we’ve just elected disqualified himself years ago when he forsook his oath to defend the Constitution by choosing to watch TV while his supporters ransacked the Capitol, there was no escaping a sickening feeling of doom, or a feeling of uncanniness that tens of millions of fellow citizens somehow felt OK enough about that option to fill in that particular bubble on their ballot. And even some people I know who did so admitted to dismay at how our political system had come to this.

But if there was no good place, there could have been many worse places to be than where I found myself last Friday afternoon, standing on a dimly lit platform above a giant steel pipe that snaked through a tunnel hewn from solid volcanic rock. The pipe, big enough to accommodate a subway train, carried water from Lake Mead down into the bowels of Hoover Dam, where it cascades into turbines to generate electricity.

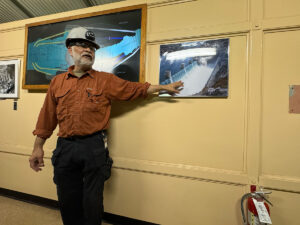

The engineer who escorted my group was soft-spoken, but it was clear as he wound through the lists of superlatives—tons of concrete used, water pressures produced, megawatts of electricity generated—that he took immense pride in his work.

The engineer who escorted my group was soft-spoken, but it was clear as he wound through the lists of superlatives—tons of concrete used, water pressures produced, megawatts of electricity generated—that he took immense pride in his work.

The designers, he said, had to come up with a novel means of cooling the dam’s immense mass of concrete, running a maze of pipes filled with cold water through it to draw off the heat concrete generates as it cures. Had they not done so, he said, the dam would still be curing today.

The generators in the paired powerplant buildings at the dam’s base—one in Nevada, one in Arizona? Each housed a giant rotor assembly weighing 600 tons. When one needed to be repaired, two cranes that run below the giant’s room’s ceiling lifted the rotor out and carried it into an adjacent machine shop. Such repair work was simultaneously an act of brute strength and incredible finesse, for repairs had measured to within fractions of a millimeter.

“You know how when something’s off in your washing machine, it wobbles?” he said. “We don’t want that happening with a 600-ton machine.”

There were other more sobering statistics, too: like that upwards of 200 workers died constructing the dam, during the height of the Great Depression.

Or that because climate change is likely to continue shrinking the Colorado River there is a less than 1-in-100 chance that the dam’s giant spillways will ever be needed again to divert water from an over-full Lake Mead around the powerplant. Far likelier is the dismal scenario of “dead pool,” in which the reservoir level drops below the dam’s water intakes, making it impossible both to generate electricity and to convey river water from above the dam to below it. This is a prospect that is a nightmare scenario to planners who allocate water to central Arizona and southern California.

But the theme of the day hewed closer to “we can accomplish amazing stuff when we work together.” We learned that in 1928, just before Hoover Dam was built, a new dam collapsed at midnight in San Francisquito Canyon north of Los Angeles, unleashing a 140-foot wall of water that killed more than 400 people as it rushed downstream. The tragedy ended the career of William Mulholland, LA’s notorious water czar, and also ushered in a new era of dam safety.

Hoover Dam, designed to corral the rambunctious Colorado River, would have to be different. Engineers knew there were two ways to make it safe: implement a “gravity-arch” design, in which the center of the dam curves out into the reservoir above, so that the water pressure increases the structure’s stability; or simply make the mass of concrete so huge that it would not break.

The stakes were high. They decided to do both, designing a structure that curves gracefully between the canyon walls, even as its base is almost as thick as the entire dam is high.

And so to me, on an autumn day when our democracy felt fractious and fragile, too easily subject to being torn by raw political ambition, the most meaningful thing I learned was what the engineer responded when one of our group asked him what the projected lifespan of the dam is. It was a question that seemed to have a shadow query behind it, a well-founded doubt about whether we can again live up to the ideals and hard work of those who came before.

When they built it, he said, they planned for it to be standing there for the next two thousand years.