A couple of Halloweens ago, the first knock on my front door once darkness descended was from two pre-teens who are daughters of a friend. One was a princess, decked out in a costume of pink meringue and froth. The other wore a strand of pearls, a chaste sweater set and a knee-length skirt. She looked like someone in front of a microphone at a political fundraiser.

A couple of Halloweens ago, the first knock on my front door once darkness descended was from two pre-teens who are daughters of a friend. One was a princess, decked out in a costume of pink meringue and froth. The other wore a strand of pearls, a chaste sweater set and a knee-length skirt. She looked like someone in front of a microphone at a political fundraiser.

What are you? I asked. She rolled her eyes and answered with obvious exasperation: I am Nancy Drew.

Nancy Drew? The supergirl sleuth who was my super deluxe childhood hero? Girls today are still reading the adventures of the fictional feminist character created 85 years ago? I imagined that Nancy Drew had become a curious antiquity, something as obsolete to today’s girls as Kotex and girdles.

When I was 9, I had already amassed a couple dozen Nancy Drew mystery books with their yellow spines, illustrated covers and benign storylines. With Nancy as our role model, my best friend Andrea Grigsby and I fashioned ourselves into Patty and Penny, neighborhood detectives. We rode our Stingray bikes, looking for clues. We carried tiny notepads and wore knee-length A-line skirts, knee socks and penny loafers. We trolled the neighborhood looking, watching, at the ready for action. Into our notebooks we penciled things like, “The flag on the Johnson’s mailbox is up.” We didn’t have real mysteries to solve, we just wanted to be Nancy Drew more than we wanted to be the women we saw on TV.

Nancy had pluck, smarts and style. In an era of Barbie dolls, Twiggy, Ozzie and Harriet, and women largely defined by their looks or their ability to keep their kitchen floors shiny, Nancy was intrepid and independent. She gave me an idea of someone I could be, someone who used her mind, someone out in the world paying attention and taking chances.

In a book about Nancy Drew, writer Bobbie Ann Mason characterizes her “as immaculate and self-possessed as a Miss America on tour, as cool as a Mata Hari and as sweet as Betty Crocker.” I characterize Nancy Drew as brave and bada**.

In the original books, Nancy is 18 and motherless. She lives with her dad, Carson, a criminal defense attorney, and a kindly housekeeper, Hanna, the maternal stand-in. Nancy’s friends Bess and George and her beau Ned Nickerson are Nancy’s A team. She drives a convertible. She speaks French. She’s strong willed. What’s not to like? Nancy made curiosity, asking questions and being smart cool. And it seems she has staying power.

In the original books, Nancy is 18 and motherless. She lives with her dad, Carson, a criminal defense attorney, and a kindly housekeeper, Hanna, the maternal stand-in. Nancy’s friends Bess and George and her beau Ned Nickerson are Nancy’s A team. She drives a convertible. She speaks French. She’s strong willed. What’s not to like? Nancy made curiosity, asking questions and being smart cool. And it seems she has staying power.

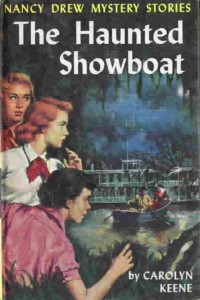

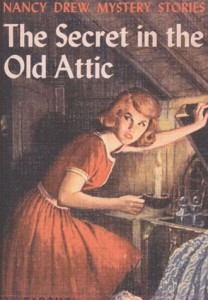

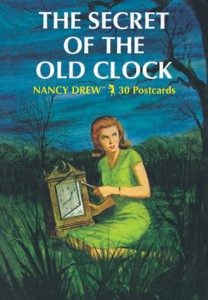

The Nancy Drew mystery books were first published in 1930, just 10 years after women were given the right to vote. The books, with titles like The Secret of the Old Clock, The Mystery at Lilac Inn and The Hidden Staircase, targeted girls between the ages of 8 and 12 and were hugely popular through the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s. The books were ghostwritten by a stable of writers who shared the pseudonym Carolyn Keene.

There were many Carolyn Keenes; the original and most durable was Mildred Wirt Benson, a journalist who wrote 23 of the first 30 Nancy Drew books. Benson was the first woman to earn a master’s in journalism from the University of Iowa. She worked for 58 years as a newspaper journalist and wrote a weekly column for the Toledo Blade until six months before her death just 13 years ago.

In the late ’50s Nancy began to lose some of her juice as the books were extensively revised to eliminate racist stereotypes. During the rewrites, some of Nancy’s sass was edited away. In the 1980s, an older Nancy emerged in a new series, The Nancy Drew Files, and nine years ago the original Nancy Drew Mystery Stories series was put to bed. Over the years Nancy has been merchandised into games and goods. Five tepid films have been made and a handful of short-lived TV series have aired, but none captured the essence of the character, largely because they excluded the participation of the reader’s imagination. Nancy is a character for the mind, not the eye.

The underlying message beneath all of Nancy’s solved mysteries is that women can be bold, intelligent and independent. The idea resonated across social, racial and generational lines—and still does. That idea also had global appeal: About 200 million copies of the books have been sold and translated into more than 45 languages.

The underlying message beneath all of Nancy’s solved mysteries is that women can be bold, intelligent and independent. The idea resonated across social, racial and generational lines—and still does. That idea also had global appeal: About 200 million copies of the books have been sold and translated into more than 45 languages.

She’s more than a detective; she is a cultural icon and has been cited as a formative influence by a number of high-octane women, from Supreme Court justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sandra Day O’Conner and Sonia Sotomayor to former Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton, former First Lady Laura Bush, TV journalists Diane Sawyer and Barbara Walters, singers Barbra Streisand and Beverly Sills and entertainment mogul Oprah Winfrey. Bader Ginsburg said that Nancy Drew “made brains seem well worth having. She was all about smarts appeal, rather than sex appeal.”

And it seems Nancy’s appeal continues. For many of us, there is no mystery to that.

Laura Kelly is the executive director of the Flagstaff Arts and Leadership Academy. Kelly spent 2014 in the tiny, mountainous Central Asian nation of Kyrgyzstan teaching storytelling at the American University of Central Asia. Born a flatlander, she has called Flagstaff home for 11 years. Her book, Dispatches from the Republic of Otherness, is a collection of non-fiction essays about her experiences living and teaching overseas.