Sometimes the best we can do is quote the smart, funny, insightful people we know. In the early 1980s, when Mike was in grad school working as a teaching assistant his roommate, Harry, who worked as a bartender at the Pinckney Street Hideaway in Madison, brought home jokes for Mike to tell his class.

Sometimes the best we can do is quote the smart, funny, insightful people we know. In the early 1980s, when Mike was in grad school working as a teaching assistant his roommate, Harry, who worked as a bartender at the Pinckney Street Hideaway in Madison, brought home jokes for Mike to tell his class.

I wonder, when was the last time I had a truly original idea? With apologies to Bob Mankoff: “How about never? Is never good for you?”

From Austin Kleon’s book Steal Like an Artist, I learned that, “Harold Ramis … once laid out his rule for success: ‘Find the most talented person in the room, and if it’s not you, go stand next to him [or her]. Try to be helpful.’” One of the people Ramis stood next to was Bill Murray; that worked out pretty well for both of them.

Musicians quote other musicians all the time, sometimes calling those interpretations “variations on a theme.” Bob Dylan used melodies from traditional music in certain of his songs, the way Aaron Copland and other classical composers often quoted folk music in their compositions.

Over the summer, I got to hear Jerry Douglas and Sam Bush perform. Throughout the show, they made both subtle and blatant references to other musicians’ songs. Douglas inserted a lick from an Allman Brother’s tune into one of their numbers. Later he introduced “Emphysema Two-Step,” “This is a tune I ripped off a Cajun accordion player a long time ago.”

Alluding to another artist’s work can be a way of paying tribute to someone you admire, and at the same time feeding a crumb to a knowledgeable reader who gets the reference.

I once quoted a line of Mary Oliver’s poem “Wild Geese”:

You do not have to walk on your knees for a hundred miles …

I wrote:

I didn’t walk for a hundred miles on my knees.

Those who recognized the reference tapped into the power of Oliver’s poem. Those who didn’t still appreciated the beauty of the imagery in my essay about making a pilgrimage.

Our creativity, in other words, is fluid and relies heavily on those who came before. Sometimes the influence impels us to discard the ideas and accomplishments of our forebears, but we’re all swayed in some way by what we witness, read or experience. It’s Pandora’s box: you can’t un-experience or un-see what you’ve seen, and as a result, can’t help but be impacted by it. The process is an inevitable part of how we learn, how we develop our own style and how we decide who and what we’ll be.

For example: just a couple of years ago Mike and I finally bought a brand new “adult” sofa, a lovely retro design in a color I love. The significance of buying a new sofa wasn’t about reaching some state of maturity, like being old enough to join AARP. It’s a function of my extended family’s philosophy about acquisition and by extension, frugality. We don’t buy furniture: we trade it, mostly to other family members. My parents, being raised during the Great Depression in the Midwest, taught me this: if you can get something for free you make do, even if it’s not your first or even third choice.

One of our favorite phrases has always been, “Sure, we’ll take it.” We have a number of possessions that have been passed along to us at various stages of our married life: the press-back oak dining room chairs that I grew up with, my mother’s wedding dishes (fondly known as “cosmicware” and highly coveted by my younger relatives for their mid-century modern motifs), and a buffet that belonged to my grandmother’s second-best friend, who gave it to my Aunt Nina, who painted it black and then gave it to us. I am deeply attached to all these items, and have integrated them into our household as cherished relics.

We’re due this winter to take delivery on an antique Sellers table and chairs that have been in my sister’s basement since my parents moved to Arizona years ago. Before that, my dad restored it and it lived in their basement. My parents bought it from my dad’s secretary when he worked at the Military Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, who knew that it had been made in my dad’s hometown of Elwood, Ind.

Not one of us does anything on our own, in other words. We all have ancestors, mentors, cohorts, co-conspirators and relatives who have come before us, who watch out for us, sometimes get in our way, and sometimes pave the way for us to do our own work. Anyone who claims the “self-made” title is lying to him- or herself; there’s really no such thing.

Even if you only copy others’ work, if you do it long enough your personality and skills will impose themselves on the work. There’s no way around it; our egos won’t allow us to subvert ourselves that deeply.

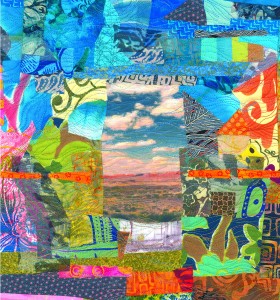

I went away a few weeks ago for an artists’ retreat, taking along an abbreviated version of my studio so I could start some new work. I had printed some landscape photos that I’d taken recently onto silk, and began interpreting them abstractly, to make a whole from the various parts. It was a way of extrapolating my experiences; being my own creative self, remembering my past influences and what it’s like to be immersed in time and space with other creatives, then letting that situation take its course. I came home with a half-dozen works-in-progress, and a new perspective for carrying into the fall season.

For an interesting perspective on plagiarism, check out Richard A. Posner’s The Little Book of Plagiarism.