I rendezvoused with a graduate school friend a few weekends ago.

I rendezvoused with a graduate school friend a few weekends ago.

Verena and I were in a class of about three dozen journalists who marauded Washington, D.C., in 1990. Most of us were print reporters. All of us were swashbucklers, young and hungry, enamored of journalism for its appealing audacities and the principles that undergirded the field. We were purposeful, we were invincible, we were ablaze.

That same year we were in grad school, CNN catapulted into history for broadcasting live television from Baghdad, where bombs were dropping. By the mid-’90s, most major American newspapers had online presences, infotainment was spreading like a venereal disease, and the internet stuck out its tongue at traditional media. The models that we had followed and the heroes that we had modeled were on their way to the dinosaur museum.

At our three-day rendezvous, Verena and I spent hours telling stories about the arc of our lives since we left grad school 23 years ago. We traded gossip about most of our compadres; all but a few have segued out of journalism. Verena lives in Berlin, raising a family and managing a newswire service, which she describes as something like being an air traffic controller. I am in Kyrgyzstan, teaching journalism in what is most likely my last hurrah in this field.

We recounted tales of our Good Old Days and segued into Things Aren’t What They Used To Be. We were wistful and nostalgic, and when we talked about grad school, we lamented the passing of a kind of journalism that had lit a fire inside us. We spoke about it with the bewilderment and mild outrage most often used when discussing recently extinct forms of wildlife.

About a week later I was back home, puttering about at the start of the day and streaming NPR’s Morning Edition. Someone announced that Ben Bradlee, the former executive editor of the Washington Post, had died at the age of 93. I crumpled. Immediate, hot tears streamed down my face.

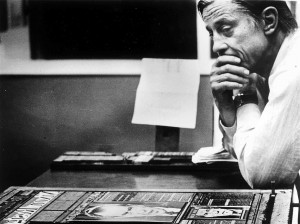

Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, two Post reporters, introduced me to Bradlee when I was in high school and read their book All The President’s Men, which chronicled the unraveling and eventual impeachment of President Richard Nixon after dogged newspaper reporting about his abuses of power when he held office. Bradlee ran the Post’s newsroom at the time. Actor Jason Robards personified Bradlee two years later when the film of the same name was released. Under Bradlee, the Post became one of this country’s most respected newspapers. He was dashing, brilliant, irreverent. He was also one of my heroes, someone who embodied much of what made journalism—and leadership—appealing, respectable and noble pursuits to follow.

Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, two Post reporters, introduced me to Bradlee when I was in high school and read their book All The President’s Men, which chronicled the unraveling and eventual impeachment of President Richard Nixon after dogged newspaper reporting about his abuses of power when he held office. Bradlee ran the Post’s newsroom at the time. Actor Jason Robards personified Bradlee two years later when the film of the same name was released. Under Bradlee, the Post became one of this country’s most respected newspapers. He was dashing, brilliant, irreverent. He was also one of my heroes, someone who embodied much of what made journalism—and leadership—appealing, respectable and noble pursuits to follow.

I continued to cry as I listened to the newscast laud him. Someone said that Bradlee had a gift for leadership and a zest for truth-telling. New Yorker editor David Remnick called Bradlee “the most charismatic and consequential newspaperman of his time.” Bradlee’s time was my time; he ran the Post for 26 years and stepped down the year I left graduate school.

I’ve thought a lot about Ben Bradlee in the past few weeks. I know that his death signifies deeper losses. Something that was alive in me is now passed. And it’s not just about the journalism I loved and made for years, the newspapers where I forged my best self that have folded or shrunken to skeletal versions of what used to be robust and thriving things.

Maybe what is over is what is over for everyone who makes their way through a life. Maybe crying for Bradlee’s passing was a way of crying for passages of my own. I think I cried the way we all cry from time to time.

I cried for the people I used to be near who are near me no more. The ones who shared my passion and my youth. I cried for my hopeful, unblemished self, the one who had not yet accumulated loss. I cried for the young journalist I once was, full of brio. I cried for what was that is not any more.

Some days I mourn the losses. Other days I am reminded that back when Bradlee was at his zenith and when the world was a big bowl of yes, I glowed in the dark. I know now that has helped me light this longer journey that continues to unfold.