I grew up on a flat patch of landfill just north of Palm Beach called Singer Island, a place named after the 23rd child of Isaac Singer, the sewing machine millionaire. My family lived a blemish-free, resolutely middle-class life two blocks from the Atlantic Ocean.

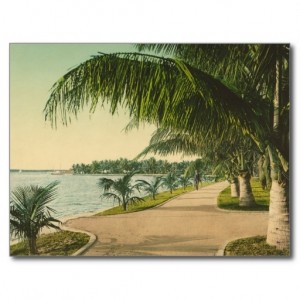

What I remember most about my childhood is the milky blue-green of the ocean and the light itch my skin felt when salt water dried on it. My mom shepherded us five kids to the beach almost every day. She filled a thermos with Fresca, packed a sheet and some poles to bivouac us against the sun, stopped at the Greater Gator for a box of powdered donuts, and off we motored to a stretch of the road thick with sea grape trees. Once encamped, we spent hours building sand castles, bodysurfing, skipping shells and squealing as we outran the waves. The beach was brown sand and seagrasses and soft dunes. No buildings; high-rise condominiums and resorts had yet to infest.

My childhood strip of beach was undeveloped, but the South Florida I grew up in was already a Mecca for people from elsewhere looking to live out their lives barefoot and in sunshine. Instead of buttes and mesas and canyons, the landmarks were strip malls and subdivisions. I was mesmerized by the ocean’s undulating vastness, the way it curled onto itself as it met the shore, the shapeshifting and the lulling sound. My child mind didn’t catalogue it this way then, but I know now I read the ocean as a metaphor for promise and continuity and limitlessness. The land had no lessons for me; its frequencies were jammed. Water taught me what I needed to know.

When I was 10, my family left our beachside town and began another life. We moved to Florida’s interior. It was terra incognita, marked by shaggy swaths of palmetto scrubland, the lilt of sugar cane fields and loamy earth planted with bell peppers and squash. We lived in Indiantown, population 600, at my grandfather’s ranch, a word that might suggest living arrangements far more posh than the double-wide trailer seven of us shared.

That year turned my life upside down, but I was already on my way there. Our living quarters were cramped, and I chafed against the responsibility I was given to assume as the oldest child. All that dropped away outdoors. Outdoors it was the New World, and it was mine. Landlocked, thick with the hazy thrum of crickets, green and scratchy—it was foreign to me, exotic and full of mystery. I knew water; land was another language.

After our school bus barreled down Fox Brown Road and deposited us at the gate, we ran to the trailer, dropped our book bags and marauded off, mooing at cows, swimming in a cattle watering hole we called Walden Pond, and spying on Butch, the lone and laconic ranch hand. My brothers and sister and I were free to roam and explore. Our trailer was set about a mile off the road. Barbed wire fences demarcated a few pastures for horses and cattle, but most of the land was open, unfenced, unmarked by anything that said no. I spent a lot of time on my back watching the clouds, listening to wind swish through the stands of pine trees. I was alone to discover and invent. In those glorious afternoons I was both enfolded and free.

I know now that I was beginning to feel the gravitational pull of forming my own self. I had begun to intuit the contours of a world larger than my school, my house, my family just as I had begun to explore land more vast and wild than anything I had known before. I felt safe in that openness, encouraged toward independence and solitude, introduced to reverence. I see now how the land sparked me, shushed me and opened its arms. The unbridled open landscape helped form a place inside my nascent inner landscape, which has its own potent grammar.

Back then I was told I could stay out until dark. And so in the rich, thickening late afternoons, when the light began to ebb, I scanned the horizon for the lights of home in the distance and turned in that direction.

I still do.