I will be attending a wedding soon back East as a guest—something I know a few things about. It is always a journey of hope, promises and pitfalls. Rather than dwelling on the latter, let me just say that I am honored to be among the throngs of well-wishers and metaphorical breezes that launch this ship of dreams.

I will be attending a wedding soon back East as a guest—something I know a few things about. It is always a journey of hope, promises and pitfalls. Rather than dwelling on the latter, let me just say that I am honored to be among the throngs of well-wishers and metaphorical breezes that launch this ship of dreams.

I have attended many weddings out here in the West. I have even officiated a couple of them, which I am happy to say are still intact. It’s always exhausting to see how much love and labor goes into making one happen. I have been in more than my share of this beautiful mess I call my own. That being said, I am happy to just be in the cheering crowd. The summer of 2010, I attended close to eight different weddings here in northern Arizona. That was quite a number. These consisted of ones very formal in context with tuxes and white gowns, and ones borne out of bohemian and organic sensibilities.

I have been to many Dineh weddings and ones inspired by that world. That is what I know: the unions blessed by blue cornmeal and the cosmic beauty of the ancient Dineh II’geh’ (wedding). We will be flying into the rising sun soon with all of these promises knowingly in our hearts. Into the east, the direction blessed by the White Shell, the vessel of truth.

This occasion also invites musings on the topic from my own world. There is much preparation for this grand occasion. As all cultures create this in their most beautiful ways with rituals, such is the case among my people. We first must know our clan system and where to put our heart and spirit attuned to the spiritual realm. There are more than 70 differing clans among the Dineh, and with this knowledge we introduce ourselves with it, placing our primary clan as who we are first. Being that we are maternal in our lineage of clan networks, my clan is Todi’chiini’ (Bitterwater), and that is who I am primarily. My father’s clan is Ashii’hi’ (Salt) and my maternal Grandfather is Dlizzi’Laani’ (Manygoats). My paternal grandfather is Tsi’na’jinni’ (Dark streaks across flesh). Knowing this, I would never fraternize lustfully within any of those networks. It is forbidden today as it was even in legendary times. Stories of great upheaval and calamities of communities as well as within the individual are enough to keep us from crossing into taboos and desecrations. Unfortunately, my clan system is the most numerous among my people and that is why I always found pickings to be very slim for my clan pedigree. Everyone I meet within my tribal interest seems to be part of those four clans. I always err on the side of spiritual caution.

When a young couple meet and develop an earnest interest, they must search their clan systems. Word gets to the parents and they will agree providing it’s all within the bounds of this ancient union. Few objections may result from other details such as infamy, personal lack of a drive and questionable lineage. The date is set and a dowry is agreed upon by the parents of the couple to be. Of course, the greater the offer of dowry, the better the chance and outlook. I have seen a few heads of horses, cattle or sheep driven into a wedding compound to set the final negotiations. Saddles and hardy jewelry as well as rugs and other fabrics of wealth are usually included as well—things useful and worthy. (I have incomparable paintings). The dowries are offered by the prospective groom to the potential bride’s family. It is then her family’s decision.

The bride-to-be and her family ready the wedding hoghaan and all is set in a festive mood. The relatives from far and wide gather to be part of this beautiful and hopeful event. Horses are tethered beneath pinyon trees, trucks are parked haphazardly all over the sheep camp. The aroma of roasting mutton and the silvery laughter and conversation rise out into the open sky. The bride-to-be, she is bathed, dressed in her fineries and fussed over by her maternal elders. The blue cornmeal batter is prepared carefully and set in a woven wedding basket. The medicine man and other paternal elders shuffle into the ceremonial Hoghaan reverently yet in merriment. The early afternoon sun kisses every face into a greasy smile. Happiness is in the rays and in the air. The bride, adorned and shouldering a colorful blanket, awaits the groom-to-be and his entourage to arrive on horseback. “Ah’de’ o’ne,l!” someone shouts. “Here they come!”

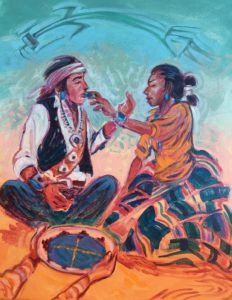

The groom-to-be and his party arrive bearing gifts of dowries and settle into the wedding hoghaan. He too is dressed in his finery—headband or a Stetson with turquoise and a turquoise necklace and Ke’toh (ceremonial bow guard). A short procession of the bride bearing the wedding basket and food to be consumed is brought into the hoghaan and laid out on the earthen floor. She takes her place in the western side of the sacred circle, to the left of her groom. The hoghaan is colorful with tribal decor and decked-out guests. Everyone sits on the floor. The medicine man blesses them both at this time; beautiful prayer of perseverance and renewal. From the four directions of the wedding basket crossed with corn pollen they feed one another a dab of the blessed blue cornmeal, and one from the middle. The rest is passed to the audience who takes a dab to bless and feed themselves. A promise for them as well.

The floor is now open to advices from the elders and anyone with positive words. This takes a while, after which the feasting ensues. Other gifts from the guests pile up at the foot of the newlyweds. Words of wisdom trickle in throughout the meal. This holy union, beautiful and enduring is launched. The direction of the White Shell holds sacred promises always. I will have that prayer in my heart for the young couple as I am in the throng of clinking glasses. Here’s wishing you all a blessed wedding season.