Texas 1960

Texas 1960

My sister Kathy was trying her wings a little. She was dating a wild boy. Mama was concerned about her so she asked our elder brother Eldon to have a word. I was with Kathy in the park, an oak-shaded area near the well house where we spent summer hours. Eldon pulled up in his two-tone Desoto and took a moment to light a cigarette before he exited the car. My brother was a handsome man, short with dark curly hair and a world-weary cynicism I admired. He looked at Kathy. “You’re a mean motor scooter and a bad go-getter,” he concluded through a cloud of smoke. I listened as he gave her savvy advice about life’s realities and joked about dealing with our angry father.

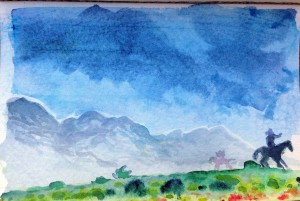

Wyoming 1976

I could smell the plum thickets in the early morning drizzle. Their apricot-colored leaves smelled sweetly of frost and the coming storm. A flock of wild turkeys flat footed through the puddles on the dirt road in front of me and took wing. As I moved from forest to prairie, a group of antelope raced alongside my Firebird in the narrow ditch until they found an exit through a gap in the fence. An enormous metal barn lay at the end of the endless ranch road. It dwarfed the much older ranch house and unpainted outbuildings that sheltered in a grove of ash and elm trees. As I pulled into the yard the drizzle changed to sleet and the sun’s light weakened. I backed my car up to the barn. There were several cowboys gathered in the light of the open door, working on foul weather projects by a hissing propane heater. One was replacing the latigo strings on a saddle, another tinkered with a chainsaw. I unloaded my shoeing box from the trunk and then the 13- pound Peter Wright anvil. The rancher brought out the first horse. He held it while I tied on my leather apron and went to work, scraping the hooves clean of packed manure and making the first cuts with my curved knife. The sleet turned into a heavy fall of fluffy white that blotted out the nearby ranch house.

The group of men talked and joked as I worked through the string of horses. They discussed the weather, the individual horses and hunting. I was trimming a nervous appaloosa mare when the conversation drifted to leaving home. An older cowboy stepped to the door and spat a string of tobacco juice into the wall of white. The appaloosa tensed.

“I was 15 when my daddy beat me for not filling the woodbox,” the cowboy said. “I figured I was too old for that so I saddled up my pony and headed out for Belle Fourche 150 miles away, where my brother lived. I left the roads and struck out cross-country through the open prairie. There weren’t many fences then and I would ride all day and see no one. I can still see every foot of that ride in my mind’s eye. I never went home again.”

I worked on the horn-like hooves with nippers and then rasped them level. While the storm gusted I made the horseshoes ring on the anvil with my big hammer. Each man told a story of a violent confrontation with their father that resulted in their leaving home.

Arkansas 1967

I had recently celebrated my 17th birthday. I sat on the porch of my family home. It was a spring morning and the air was filled with the fragrance of redbud and dogwood blossoms. I could hear Daddy’s voice from the kitchen as it grew louder and more angry, the cursing more intense. I went to the kitchen door in time to see him throw his plate of breakfast at Mama’s face. He jumped to his feet and grabbed her arm. He showed no surprise when I pulled him away, though I had never defied him before. He unleashed the freight train of his fury on me; punching with work-hardened fists and slamming me into the walls and furniture. I didn’t fight back but I wasn’t able to disengage from him until he kicked me down the front steps and I rolled into the yard. He had spent himself and he leaned against the door jamb gasping for air. As I stood to my feet he told me, “Get out and stay out.” My sheltered upbringing included no training for making my way alone in the world. I was hurting but the terror of the unknown overshadowed the bruising. In a numb cloud of disbelief, paying no mind to the farms, streams and cows grazing in meadows, I walked the four miles to the next town where my eldest sister lived. Jo Ann had a house full of kids, but she briefly took me in until I rented a tiny cabin behind the Methodist minister’s house.

It would be decades before I quizzed some of my older brothers about the circumstances of their leave taking. They told stories that echoed my experience. I found my brother Eldon at his office at our local newspaper where he was editor and owner. We talked about how Kathy had made an exit plan by securing a job at the meatpacking plant in Abilene and arranged to move in with our sister Shirley to be close to her job. When I commented that it was a miracle our siblings had made it on their own in the big world with the little practical instruction we received at home, he smiled. He reached into a file drawer and pulled out a back issue of the newspaper. He handed it to me and I read the story he had written as an editorial:

“When I was a small boy my mother gave me a bullet for Christmas. It was one of those big ones—like deer hunters use, and it was such a special gift that I always carried it with me in my shirt pocket.

Many years later I found myself in Las Vegas, Nevada, on Christmas morning. It was a cold, lonely morning and I found myself wandering aimlessly down Charleston Street in downtown Las Vegas. Familiar carols drifted down to me from a second story window in a drab brick building. When I glanced up I could see that a spiritual religious meeting was taking place in this cold, uncaring town.

The carols stopped abruptly and the crowd became even more spirited and the shouts became louder. Suddenly—without warning—I heard the crash of flying glass and saw a Bible come out of the upstairs window and directly at me. I was unable to dodge the missile and all went dark.

Stunned, I slowly stood up and felt a devastating pain in my chest. I reached into my shirt pocket and retrieved the crumpled bullet.

Saved! By my mother’s bullet!”

Although he delighted in teasing Mama about her deep reliance on religion he appreciated her steadfast devotion. Eldon inspired me to use humor to defuse violent situations and deal with things that seemed insurmountable. In a real sense I was “Saved! By my brother’s bullet!”

Tony Norris is a working musician, storyteller and folklorist with a writing habit. He’s called Flagstaff home for 30-plus years. Visit his website at www.tonynorris.com.