“Drawing is more than a tool for rendering and capturing likeness. It is a language, with its own syntax, grammar, and urgency. Learning to draw is about learning to see. In this way; it is a metaphor for all art activity. Whatever its form, drawing transforms perception and thought into image and teaches us how to think with our eyes.”

— Kit White, from 101 Things to Learn in Art School

The very first stirrings of “thinking with my eyes” as a means to create my own world, filled with subjects and symbols of my unconventional and safe reality, came early. My great Dineh’ elders carried in themselves the wisdom and strength born of the act of symbolizing our mythic world through the healing sand painting mandalas. I was intrigued by these ancient templates. I saw magic flowing from their thick and knowing fingers. To my innocent eyes it was as if these existed in another holy place, and were being released from where they already resided. They were the reservoir where magic healing sources awaited.

The very first stirrings of “thinking with my eyes” as a means to create my own world, filled with subjects and symbols of my unconventional and safe reality, came early. My great Dineh’ elders carried in themselves the wisdom and strength born of the act of symbolizing our mythic world through the healing sand painting mandalas. I was intrigued by these ancient templates. I saw magic flowing from their thick and knowing fingers. To my innocent eyes it was as if these existed in another holy place, and were being released from where they already resided. They were the reservoir where magic healing sources awaited.

I saw my uncles and my older brothers and cousins render amazing images on the dirt floor of the ho’ghaan. The lines were accentuated by the amber light of the kerosene lamp as shadows danced mysteries on the cribbed log walls. I sat in awe of the voices relating ancient stories of heroes and coyotes which they illustrated with stick drawings right there on the floor. I knowingly picked up my own stick and connected my heart and my head to my hands and I drew my first line. In my mind’s eye I sketched my horse. The lines were devoid of mass and my brother chuckled. “You cannot call that a horse,” he told me before guiding me into that lesson.

My Uncle Harry, from the corner came to my defense. “That is Spirit Horse. Do not mock him.” My Uncle Harry, unbeknownst to my brother, had nudged that first hesitant line into one of confidence.

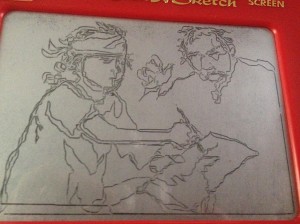

I developed a love for those defining lines and the motion of the hand before I honed the skills to render a horse. My older brother Nelson taught me to draw animals correctly, using circles of varying sizes and connecting them with lines and mass, much as it is taught in art class. Armed with this knowledge, I was a bit ahead of the other boys in school. It was because of their passing interest in a new toy, the Ohio Arts Etch A Sketch, that I acquired several of these magnificent toys. It reminded me of the sacred and magical images of the sand mandalas. The boys tossed them after a few attempts, which produced nothing more than straight lines. They went back to their checkers and cap pistols. I cautiously nailed a circle, some curves and then squiggles. For me it was both temporary, and personally healing. The first line that was to be my life was drawn.

“Dii’ dashiki’ yaazhi’ ayoo’ na’adjaa,’” (This little man can draw) an elder said as I produced another wood fire charcoal drawing on cardboard. I was immediately recruited, and for the next several years I sat hunched over the blessed bed of sand, earth colors spooling from the fingertips of my small untested hand. I felt honored and sacred and it also kept me from harder chores. I learned to stay within the perimeter of that ancient set of templates. I found my chosen place in those days on my knees, face close to the ground, moving to the rhythm of healing chants.

Back in the confines of the boarding school, I continued to create my world away from ceremonial art. I saw that all of my world needed my validation, my vision and meditation within it. I drew superheroes, some existing; others made up in my wild youthful whirlwind of a mind. I drew my cowboy heroes and DC Comics’ Sgt. Rock and some of Marvel’s bulky characters. I drew Sad Sack, the comic army private that always seemed to end up in a garbage pail with a banana peel as a cover. Turok, the lost Sioux in the land of the dinosaurs was another great inspiration.

Movies shown at school gave me yet more characters to give lines to. Later came various forms of music that set tempo and emotions to draw upon. My world offered up much to meld into constant hand motions. It was during these days that I discovered that I did not need any material to draw. I drew on air with my finger—images only I could see, for as long as I wanted.

“Yee’ya’ be’iini ziin” (Be careful, he is a wilding wizard) the uninspired called out among themselves. Bullies kept their distance. In this manner I managed to survive the most brutal years of the government boarding school.

My drawings gave richness and meaning to my life as a young boy. Even my older sister was impressed enough that she coughed up a quarter for me to draw her the face of Elvis. That was not too hard. I made his face a cartoon and she refused to pay. But my passion was never about quarters. When I was at a vulnerable age, drawing helped me survive in a rapidly changing world. It was insulating me with very ancient scripts that carried my story and my fantasy. Drawing gave me more than an immediate contact to that world we call spirit. My late grandmother confirmed that by telling me the gift of seeing is the power to render within a perimeter of the Dineh’ philosophy of Spirit Break, and to realize you are always creating, and to know what things you can and cannot represent, such as lightning, sacred “yeii’” (deity figures) and serpents. To this day I never draw them without considering this.

I draw now to record life’s thumbnail sketches. I cannot handle a camera so this is my aperture through which my documentations take shape. I draw to keep that channel to the magic world open. I draw my longings, my fears and my little celebrations in living. I want it to be a reservoir of my passion that brings a smile to every face that comes in contact with it. The knowledge of drawing is the armature upon which all other forms of art find its impetus, its aesthetic in form, motion and sound. Just as my very first cry rang off the mesa on that cold winter’s night many years ago, my very first line in art gave purity and oxygen to all that is yet to come. Yes, come mar the blank space to define your own first cry. Happy drawing to you.