I had a brother once that I looked up to, to no end. I had a brother once that loved me through expressions of the face and words, and yet still he beat me up when I transgressed in my young boyhood as I learned to be a man. Nelson was two years older than me and my closest sibling. He was a charismatic child, and at an early age even the animals gravitated to his charms. He was my brother. I loved him. He exuded what I wanted to be, but could never achieve. I felt he was Charles Atlas, Jim Shoulder and Marlon Brando all in one. The tales of his young bravado on the Rez preceded him. My brother Nelson was my hero. He always felt fine being a “Nelson.” I could never be comfortable with my government name of Wilson, however—a sound I answered to but never truly was. It was a strange time in the late 1960s and early ’70s. I knew my brother well. We became men together on the backs of wild broncos and ponies and we rode hard and unimpeded for miles through the Kleetla Valley of Shonto, Ariz. We rode together and mimicked our great celluloid heroes Gary Cooper, Alan Ladd and Victor Mature. We were free to be our TV western heroes as we flew among dazzling snake weed and sagebrush through the Upper Sonoran desert.

I had a brother once that I looked up to, to no end. I had a brother once that loved me through expressions of the face and words, and yet still he beat me up when I transgressed in my young boyhood as I learned to be a man. Nelson was two years older than me and my closest sibling. He was a charismatic child, and at an early age even the animals gravitated to his charms. He was my brother. I loved him. He exuded what I wanted to be, but could never achieve. I felt he was Charles Atlas, Jim Shoulder and Marlon Brando all in one. The tales of his young bravado on the Rez preceded him. My brother Nelson was my hero. He always felt fine being a “Nelson.” I could never be comfortable with my government name of Wilson, however—a sound I answered to but never truly was. It was a strange time in the late 1960s and early ’70s. I knew my brother well. We became men together on the backs of wild broncos and ponies and we rode hard and unimpeded for miles through the Kleetla Valley of Shonto, Ariz. We rode together and mimicked our great celluloid heroes Gary Cooper, Alan Ladd and Victor Mature. We were free to be our TV western heroes as we flew among dazzling snake weed and sagebrush through the Upper Sonoran desert.

We played rough and real. Once I roped him while riding at a full gallop and dragged him half a mile. Once I held his head underwater with a Bowie knife in my palm. I did not believe death happens with horses around. The BIA school we attended away from our brotherly adventures showed us bad B-westerns. We saw the actor running amok with his bunch. I was always concerned about who would get the beautiful saddled pony that an outlaw was shot off of. Who gets the horse?

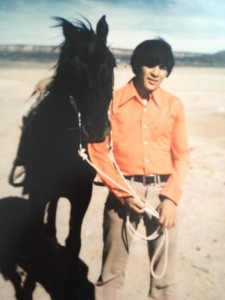

Let’s return to my brother Nelson. He was a horse whisperer from a young age, a very fine example of old-school cool. Horses were his best friends and confidants. Every horse I have ever mounted, I did with an awareness of his gift—with his name on my lips to its ears. I never saw him mistreat a horse in the slightest. I never saw a man look so good on the back of a horse.

It was not the trappings of a cowboy that attracted him, but rather the girls that came later. It was the girls with whom he whispered the best. Girls flocked to him. Young men adored him and some of his mean detractors as well. He had few fights and walked away the picture of a victor, calm and respectful.

During summer ceremonies boys claimed his friendships to get in the right “bunch,” not gangs. I saw the sweeter side of him slowly retreat as the hero on a mission, clenched fist answering clenched fists. I survived most on the edges of ceremonies because I was the little brother of a man respected, loved and hated as well. I survived those harsh and darkened peripheral grounds where others’ blood trailed off into an old pickup truck and sage flats. I survived and tried to be my own man. I lived in his shadow and he wanted me to be tough. He told me he was not always going to be around. “Live hard, die young and leave a good looking-corpse,” were words I heard him say. He did. I remember going into a packed bar one night and he pointed to a girl in blue jeans who looked every bit like Debra Winger’s character in Urban Cowboy (1980). “I am going home with her,” he promised. He did.

What do you say to them? I asked of him. He’d tell me to learn on my own. He respected women and defended them with a passion. They came to his defense more than once. If anyone had a silver tongue, this guy did. He quoted lines from great books and films. A learned man who fears little leaves hard shoes to fill. I tried in my own way. I feel that as a young, gentle and sensitive boy I was forced to be tough and to carry a chip on my shoulder and deliver those challenges in a quivering voice.

When he joined the U.S. Marine Corps I saw him even less. When he returned he was a shell of the man I knew. The bravado and the cool ways with which he picked up women waned. I coursed unscathed through the summer ceremonies and the Kayenta Field House escapades mimicking my brother. I became a weaker version of him and still held my own.

He came home later, but not back to the sheep camp. With his beautiful girlfriend, Dianna, they had a successful show horse business down in the Valley. I saw them now and then. They loved and fought on nights that alcohol labored the voice and the heart. He started drinking hard. In the end he knew and I knew. We shared a dream where I could not let him back in—not out of anything other than fear of an unknown weight forcing the door open.

I held on as the trying stopped and I knew whatever was outside my sanctuary was gone. In the dream of Yucca Spine Thunderstorm, little survived. Looking up from gathering firewood he seemed sad as though he had given in.

He took his last walk early one frosty morning. He promised the still sleeping siblings and nephews he was going to kill the coyote that had been taking all his joy of being a shepherd. His last walk ended in the report of a rifle. It must have been a decision he made beforehand. Dianna and he were doing well and even talking of marrying.

His younger brother found him there on the frozen ground 200 yards from the hogan he was born in. He ended his own life two days after Christmas and less than a week before his 33rd birthday on New Year’s Day.