The year after I graduated from high school, I crisscrossed the U.S. in a flotilla of Greyhound buses with about 150 people my age. We were one of three traveling casts of Up With People, a wholesome performance troupe singing across small town America and spreading a message of global goodwill.

The year after I graduated from high school, I crisscrossed the U.S. in a flotilla of Greyhound buses with about 150 people my age. We were one of three traveling casts of Up With People, a wholesome performance troupe singing across small town America and spreading a message of global goodwill.

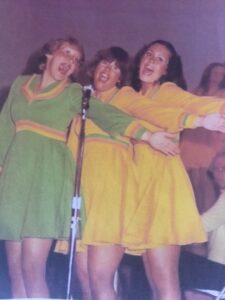

I wasn’t selected because of my superior pipes or formal training; I was chosen because I could hold a tune and I played well with others. I had sung in my grade school chorus, sung in Sunday church, sung to vinyl my friends and I would spin at slumber parties. But singing in Up With People was next level. We sang as a group for hours every week: in rehearsals, during performances, on the buses. We sang in schools, in prisons and hospitals, on stages, in amphitheaters, in downtown plazas. While I can no longer solidly remember the names of all the cities where we performed, what I can viscerally conjure is the powerful feeling that surged through me when we sang. It was warm, sudden, shimmery and profoundly stirring.

I’ve been chasing that feeling ever since–kama muta, a Sanskit word that means moved by love. Researchers at the University of Oslo’s Kama Muta Lab define the emotion as a sudden feeling of oneness, union and belonging. What my year in Up With People taught me is that singing in groups bathes me in kama muta. And the more I feel that good feeling, the more I want to feel that good feeling.

When we sing, large parts of our brain buzz and illuminate, says Sarah Wilson, a clinical neuropsychologist at the University of Melbourne in Australia. “There is a singing network in the brain quite broadly distributed,” Wilson says. When we speak, one hemisphere lights up. But when we sing, both sides of the brain light up.“What we are doing when we sing is developing this specialized network, which gives us that physiological reward hit, the chills, the dopamine release, the sense of feeling good,” says Wilson.

Singing is ancient, universal and resoundingly primal. There is no human culture on the planet, no matter how remote, that does not sing. Some researchers believe that singing preceded speech. We, as a species, sing for entertainment, for storytelling, to celebrate rites of passage, to beseech our various gods, to recount our victories, to memorialize. Some cultures sing themselves into being.

In the belief system of the Aboriginal people of Australia, songlines are the melodic, history-holding paths of the creation ancestors. The origin story goes like this: From what was a vast void, the Dreaming began. Creation ancestors sprang forth and began forming the earth. As they travelled, they created living things and the landscapes that would be their homes. Those travelling paths became songlines of dance and music, song and story that unfurl over generations and carry who they are.

Singing in the car, in the shower, as I push a Swiffer over a dusty floor. Singing solo just doesn’t have the emotional oomph as singing in a group. Like some spiritual adhesive, singing in groups binds us, connects us in a form of unity we can’t seem to replicate when we speak with one another. “There is evidence that, in general, singing in a group enhances our empathy and social connection,” says Wilson. “We see this at football clubs, with people in congregations and choirs at church. It’s a community-building activity because we’re united in our voice.”

Last week I spent four days in New Mexico at a singing and writing retreat. Eighteen of us had made our way by train and car seeking, perhaps unknown to us all, kama muta. There were some trained singers and some experienced writers in the group, but the workshop wasn’t about learning how to sing or learning how to write. While our leader strummed her guitar, we sang blues, show tunes and pop ditties. When the singing stopped, we bent over our journals and reflected on our voices—the ones we use for melody and the voices we carry inside of us.

In one of my journal entries, I urged myself to remember what I learned so many years ago in my Up With People days; When I sing, I am like the breath that ferries the melody. I go deep, leave my body and then rise. When I sing with others, I am enfolded and joined. I am in the presence of love.