As a kid, nothing pleased me more than to hear a grownup cut loose with a volley of curse words. I was an East Coast city girl; we didn’t say “cussing.” We said “swearing” but that was confusing because sometimes you were meant to swear, to promise you weren’t the one who made the crank calls to the elderly neighbor or clogged the toilet with paper towels. The use of naughty and forbidden words was music to my ears, a whole string of them a symphony. I didn’t have to understand what was said, it was the way in which it was said that intrigued me. Syllables were quite literally ejected from the mouth with venomous intent. The one who swore took on the characteristics of a snake, pulling back with the neck and shoulders before driving forward to strike.

As a kid, nothing pleased me more than to hear a grownup cut loose with a volley of curse words. I was an East Coast city girl; we didn’t say “cussing.” We said “swearing” but that was confusing because sometimes you were meant to swear, to promise you weren’t the one who made the crank calls to the elderly neighbor or clogged the toilet with paper towels. The use of naughty and forbidden words was music to my ears, a whole string of them a symphony. I didn’t have to understand what was said, it was the way in which it was said that intrigued me. Syllables were quite literally ejected from the mouth with venomous intent. The one who swore took on the characteristics of a snake, pulling back with the neck and shoulders before driving forward to strike.

I noticed that the most forbidden words had the harshest sounds, full of back-of-the-throat consonants and low on vowels. The f sound was popular, a good consonant gone bad, running with the wrong crowd. So when the word “philatelist” first crossed my bow, spoken by an older gentleman wearing a bow tie and carrying a briefcase, I was intrigued by what I assumed was his vulgarity, and determined to find out just how unseemly the word might be.

Philatelist, philanderer…. I was sure I was on to something. But when I consulted my Merriam-Webster, there it was, tame as a pair of old slippers, tucked between philanthropy and philharmonic. I was at first disappointed, I admit, to have pounced upon nothing but a lover of—of all ridiculously wholesome things—stamps! A philatelist. Hardly a word I could show off in school without sounding ridiculous.

Instead, I began an informal study of the ridiculously wholesome things themselves. Stamps. Every letter carried one. Stamps flew freely around the world every day, every hour, crossing borders, flouting customs officers, sailing into mailboxes behind the Iron Curtain, flying into homes across every continent and into the hands of presidents and plumbers. Right at that very moment someone somewhere was reading news of a birth, a death, a marriage, a coronation; someone was writing a confession or fomenting a revolution, and the language of these acts was broadcast to the world by means of a stamp. A humble stamp, licked and affixed! The profound simplicity of this means and method inspired me to investigate its history.

Though it seems to have been with us always, the postage stamp didn’t appear until 1837 when it was introduced in Great Britain by a school teacher named Sir Rowland Hill. Before that time, a letter’s receiver, not its sender, was responsible for paying the postage, and if the receiver couldn’t or didn’t wish to afford a piece of mail, it would be returned to the sender at the post office’s expense. Sir Roland argued that to make the business profitable, what was needed was a standard rate and for the burden to fall on the sender. The stamp then became proof of payment. The first two stamps issued in the United States in 1847 were a five-cent stamp honoring Benjamin Franklin, and a ten-cent stamp of George Washington. Ten years later, with the invention of perforations, people no longer had to use scissors to cut a stamp from the large sheets on which they were printed, but could simply tear them free. This is the look of the scalloped-edge stamps we use today.

Philatelists love stamps and all things stamp-related, but not every philatelist is a collector. Collectors sometimes pay millions of dollars for famous or unusual stamps. In November of this year a famous stamp named the Inverted Jenny brought more than two million dollars at auction. The stamp is, as it implies, an upside-down depiction of one of the early mail-carrying biplanes called a Curtiss Jenny. Due to a printing error, the biplane cruises through the sky with its landing gear pointed upward. Only a hundred of these anomalies survived their printing in 1918, and the story of their survival is filled with intrigue. Forgeries, the FBI, stamps hidden under mattresses, priceless stamps sucked into vacuum cleaners. The history of the Inverted Jenny reads like a thriller, and the error that created it has been called “one of the most prized in philately.”

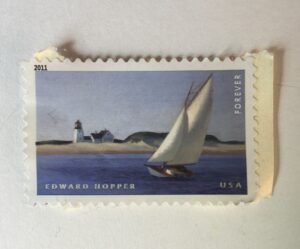

As I write this, I am sitting at my desk, looking down into the face of a stern Ruth Bader Ginsburg dressed in her judge’s robes, adorned with her now-familiar lace collar. Twenty RBGs stare back at me from the sheet of stamps I bought last week. Could there be a greater tribute to a person, I wonder, than to be memorialized on a stamp? My last batch of stamps portrayed a group of young Diné artists and their painted skateboards. I’ve sent out Rosa Parks, John Lewis, Pete Seeger and Edward Hopper, among so many other favorites. My dear friend Tony Hoagland used to say, poet that he was, “They should put your face on a stamp.” It was a high compliment and meant as such. I aspire to it still.

As words go, “philately” still seems to me one of the most misleading. The sound of it promises titillation, while its meaning places us in musty rooms where bespectacled people lean over crumbling albums of postage and delight in the back issues of The American Philatelist, the oldest philatelic journal in the world. It doesn’t escape my notice that my own particular weird interest in forbidden language is what once opened my eyes to those whose particular weird interest is postage. How fortunate I followed my curiosity. How enriched is this world by the presence of stamps.