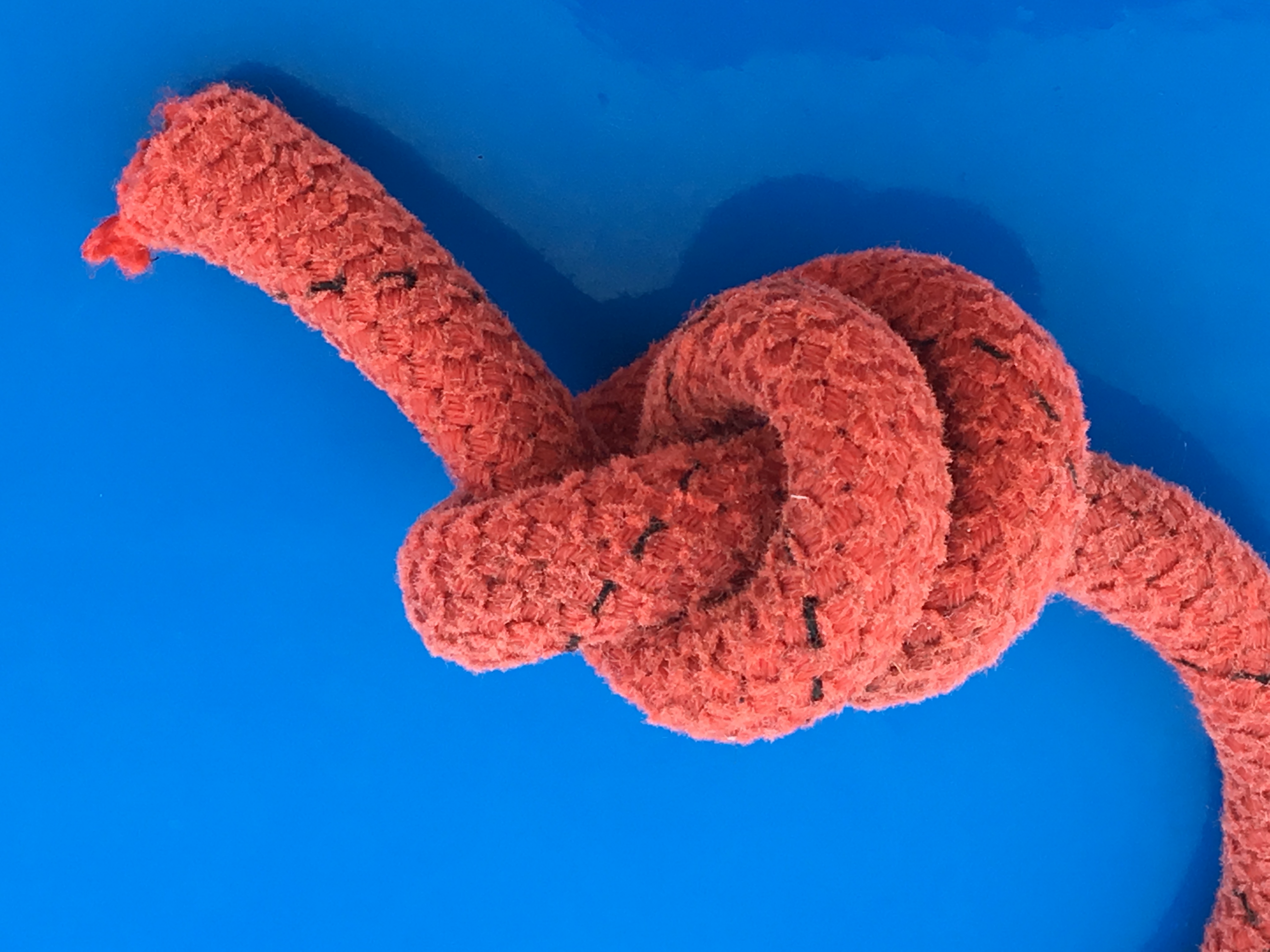

Double overhand, photo by Margaret Erhart.

When you hang around with truckers and sailors you learn the language of knots. Climbers and wranglers, arborists and roustabouts — they speak this language too. You can go anywhere in the world and find someone tying a bowline. It may be called by a different name, but it’s the same configuration: the rabbit goes out of the hole, around the tree and back into the hole. In places without trees or rabbits you’ll still find bowlines.

My grandmother had a schooner left to her by her stepfather when he died. He died the year I was born and we shared the earth only briefly, but I was sorry not to meet him. He was a brilliant and quirky man, rumored to have had a hand in inventing the television. We used to go out on that sailboat for two weeks at a time, and there were days when the fog came in and afternoons when the wind died and life got very still. That was when I pulled out my knot book and studied the art of connecting one thing to another, which is what the language of knots is all about. Within that language you have different dialects — knots of different regions or professions, like the hangman’s knot, the trucker’s hitch, the fisherman’s bend. You have knots that say what they mean: a square knot is square; a girth hitch does just that; a climber’s knot called the butterfly looks just like its name.

Knots are a physical language. All language is, of course. When we speak we use tongue, teeth, lips and lungs to travel from one sound to the next. But knots are built with the hands. They’re formed with the fingers (and sometimes, as a last resort, with the teeth). They’re a visual language as well — every beginner can see the difference between a square knot and an overhand. An international language, knots were carried on the backs of sailors as they made their way around the globe. The power of the seas was the power of discovery and mobility, and knots became a conversation between cultures, a landing place for difference and the surprise of similarity. In modern times, it’s the International Guild of Knot Tyers that carries the conversation, bestowing its stamp of approval — or not — on any newly invented knot that comes before that august body seeking legitimacy.

There are reef knots and thief knots and grief knots. There are Gordian knots and surgeon’s knots and unknots. According to Wikipedia, “a knot is an intentional complication in cordage which may be useful or decorative.” An intentional complication? Sometimes yes, sometimes no. But the knots that travel the world, the knots with names and purpose and consequences, the knots at the feet of which spelunkers and sailors, skydivers and climbers, truckers and trapeze artists kneel, those are intentional complications of the highest kind; they are evidence of a beneficent God; they are the hand of someone’s Almighty come down to save the day. You know this best if you have ever dangled on belay many meters above the ground, your limbs flailing and your vision blurred by the significant airy length of real estate below you. A prayer comes naturally at this time and often it is a prayer to the ties that bind, to the knots that millennia have handed down to you for situations just like this.

The other day I was busy tying a mattress onto the back of my truck and a man came out of the mattress store and stood watching. He was wearing a striped shirt and plaid shorts, a combination that reminded me, sartorially at least, of my father.

“You done a lot of horse wrangling?” he asked. “Or maybe you were in the Merchant Marine?”

What piqued his curiosity, I realized, was my ease and competence in securing the load. The mattress man could see I’m an old hand with knots. Start with a bowline and move on to half-hitches, then throw in a trucker’s hitch and you can bet good money that load’s not going to budge. Whether it’s a mattress or a couple of kayaks or a load of Verde Valley horse manure covered with a tarp, there will be no shifting if I’m in charge, no bits and pieces of things flying up in the air, terrifying the poor soul driving behind me. My niece once navigated an airborne sheet of plywood unleashed by the vehicle in front of her. She watched it fly up, wobble and begin to descend, her windshield directly in its path. She had the good sense to step on the gas and save her life while the offending projectile bounced off into the weeds.

I wasn’t always trustworthy when it came to knots. One significant knot failure happened when I was asked to tie the dinghy to the stern of the schooner (in English this translates to: attach the rowboat to the back of the sailboat) and did so and gave it not another thought until an hour or two later my mother suddenly cried out, “Where’s the dinghy? We’ve lost the dinghy!” It was true, we were no longer towing that sturdy little lifeboat and had no chance of finding it, ever, out on that great expanse of sea. A knot is a knot only if it holds; otherwise it’s a limp length of line.

Knots have a strange way of igniting sense memory. Half-hitches bring me the smell of salt water, even if I’m hundreds of miles from the sea. Bowlines are always attached to the red rowboat of my childhood. Slip knots, figure-eights, something called a prusik — each carries a sensory record of the past. The monkey knot, the only knot to use when attaching tarp lines, brings me the memory of Marble Canyon, the river green and noisy, and an old friend with a full head of auburn hair.

I’m always surprised at the knots people tie when they don’t know how to tie knots. In their attempts to attach one thing to another, those who don’t speak the language err on the side of quantity. Rope is wrapped around and around but never secured, creating a thick, ineffective web. The language of knots has an order and efficiency—a harmony—that isn’t present in a messy tangle of line.

“If it isn’t beautiful,” said one old sailor who taught me the first knots I knew, “you haven’t got it right.”

He may have been an optimist, yes, but let’s call it a rule to live by.