In the late 1990s I traveled with a friend to what was then called Burma, and is now called Myanmar. We never intended to go to Burma; our plan was to explore Thailand, and perhaps move on to India after that. We even obtained visas for Egypt in case we still had itchy feet.

I had never been to Asia, and in my journal I described Bangkok, where we landed, as one of Dante’s inventions, the diabolical setting for his Inferno. It was a city awake all night, not in the orderly way New York is awake all night, but in the steamy, honking, overcrowded way of other tropical cities. Jetlagged, I prowled the streets from midnight to dawn, and it wasn’t unusual to pass an open doorway at two in the morning and see an entire family—children, babies, grandparents—sitting around a table, enjoying a meal or playing a board game or tending to their home’s many altars. We stayed too long in Bangkok, and when the time came to head north to Chiang Mai, we were overwhelmed by Thailand’s crush of humanity, and instead booked two tickets to Burma.

We heard it was quiet there, a trip back in time, and there was truth to that. Rangoon was the capital city then, and its traffic was almost exclusively horse carts. I remember only vignettes of the day we arrived. Among them, a cup of English tea at the famous Strand Hotel, a place so out of time, so Old World, so cool and dark inside it was possible to forget we were sitting down to sip from porcelain cups within a country ruled by a military dictatorship.

We made a quick decision to head north to Mandalay and caught the next bus. The ride was a jolting fourteen hours with frequent stops at tea rooms, dim lantern-lit places where you might find a duck foot at the bottom of your soup. Tea stops were followed by bathroom breaks along the side of the road. As the night wore on, and not one of the women on the bus exited at these opportunities, I became curious and desperate in equal parts until I realized if you were a woman you brought a can. While the men were outside watering the trees, you did your business into the can and emptied it out the window. Having brought no can, I followed the men. They looked at me with grave curiosity and some amusement as I headed off to the other side of the road. Picture the main north-south thoroughfare in Burma, a dirt road along which people, oxen, and the rare vehicle traveled, and a foreigner struggling for comfort and conformity, relieving herself in the shadows.

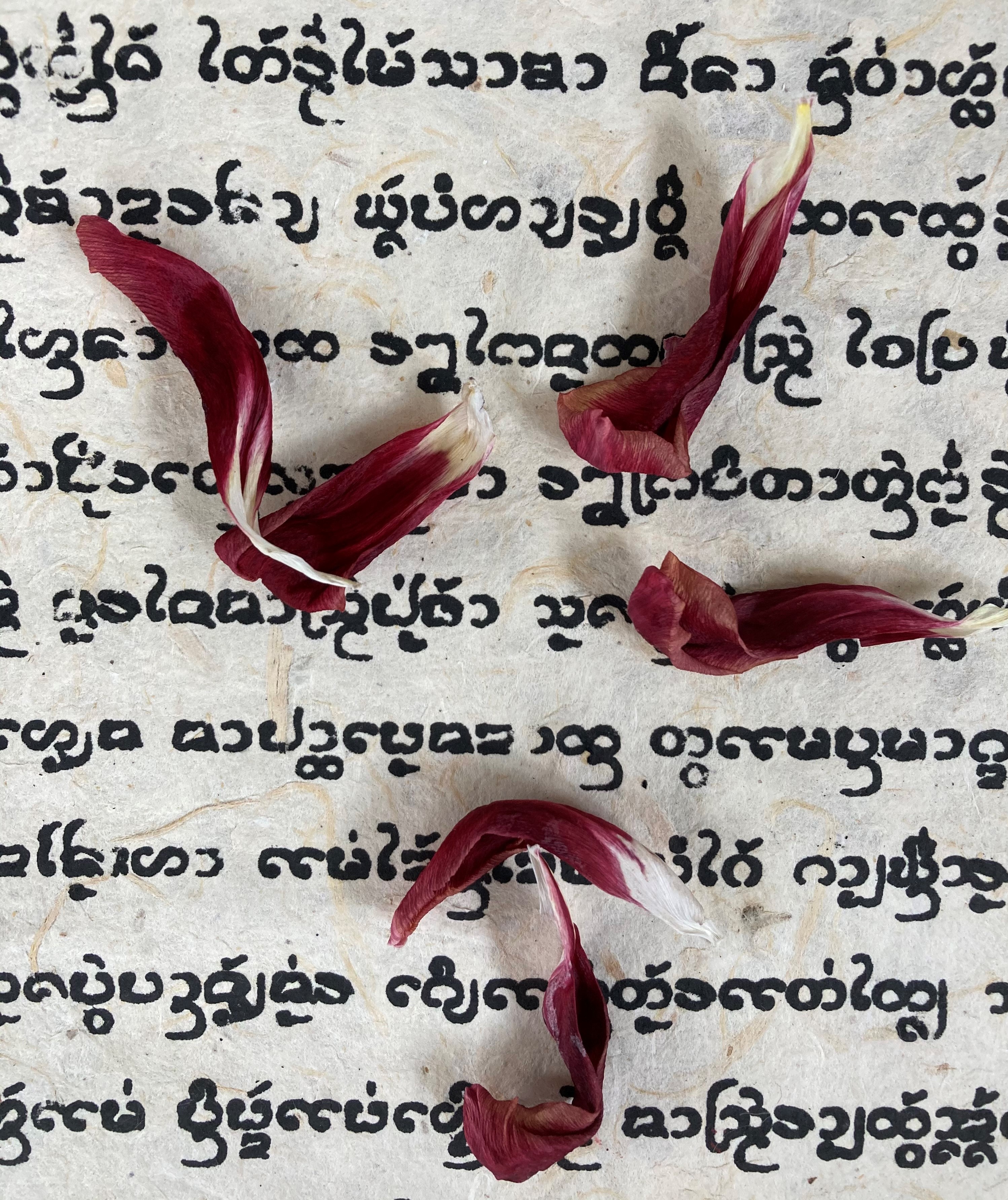

The stories we tell speak for the richness of the journey we make, and the journey we made to Burma is decorated with story after story of the intelligence, patience and kindness of the people we met there. Nuns in pink robes, little boy monks in maroon. Everyone in flipflops. An encounter with a Burmese movie star in the Dahlia Motel. A man pushing a bicycle laden with firewood. Street vendors selling bolts of cloth, little snacks called samosas, and bottles of Coca-Cola. Old women smoking cheroots, chewing betel. The Irrawaddy River running through our days like a long empty sleeve, delivering us to Bagan, the city of stupas, a landscape of golden spires.

And in contrast to it all, the short trip we made to a beach on the Andaman Sea, unbeknownst to us an R&R resort for the military. It was the only place something was stolen from us—a pair of flipflops, though the thief left his or her old ones behind in an unnegotiated trade. It was the only place where we, two foreigners, two white women, experienced catcalls. Nowhere else in the country were we singled out as women, and nowhere else was our trust and naïveté exploited. Nowhere else did we feel unsafe. The loss of the flipflops weighed on us for the rest of the trip.

We were glad to get away from that seaside resort with its undertones of unpredictability and power, a place where no one swam in the sea, and we returned to Rangoon where a family emergency cut short our travels. We had planned to go stand with the crowd that gathered once a week in front of the home of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. Her activities were sharply restricted at the time, but on Wednesdays her military keepers permitted her to appear on her balcony to give a short talk to the people of her country. It is one of the few lasting regrets of my life that I didn’t get to experience the sight and sound of The Lady, as she was fondly called. With the recent military coup she has once again disappeared from sight.

How are we to digest the events of recent weeks in Burma? My reason for writing this is to bring you closer to a place most of us have never visited, a country largely unknown. In fact, Burma? Myanmar? We don’t even know what to call it. When we can picture the people of a country, what they wear, the food they eat, the way they squat on their haunches to smoke a cheroot, they cease to be faceless. They take on a life. We care more. And their country, their home, becomes more than just a shape on the map down in the southeast corner of Asia. And when they are demonstrating for a legitimate democracy and lose their lives, they are not just bodies and numbers. They are entities with a past but no chance now to create a future.

Call this a portrait of a people and a country that won my heart a quarter-century ago. Their suffering saddens me, and their courage continues to inspire.