Sometimes it seems like one sentence is enough for an essay.

No, I don’t mean that one. Or this one. I mean one like this:

Yesterday morning, Saturday morning, I went outside on the patio and it had sprinkled a bit in the night and the air felt so much more alive than it has in many weeks, and within the next hours the election results were announced—the latest, most definitive ones—and the month’s first winter storm blew in its with rain and sleet and snow.

Joe Biden called them “inflection points” in his speech that night—the moments in time when a narrative shift happens that significant enough to represent a change in a society’s trajectory. An inflection point is a knee joint, a pivot when things move off in a new direction. Or at least have the potential to. An inflection point carries a world within it, linking as it does its dense concentrate of the past with tantalizing future possibilities.

And after a dry summer and a dusty, too-warm fall I carry deep within me the hope that a November storm—even a small one like the one that was huffing and sleeting outside our living room while we watched Biden’s speech—will be an inflection point, only a prelude to a big walloping winter of heavy snows that recharges springs and aquifers and spirits.

It is widely considered a pathetic fallacy to ascribe human emotions or motivations to the natural world. To suggest, in other words, that the Southwest’s exciting weather this past week would in any way be linked to the sort of collective decision-making that millions of American voters have made in recent weeks. But this idea of a pathetic fallacy is closely tied to the very Western, and very harmful, idea that there’s a big gulf separating humans and the natural world.

We know now that there isn’t. If there is a silver lining to the climate crisis maybe it’s that a big spike will finally be driven into the heart of that misguided idea. Humans are clearly empowered to alter the entire global climate—and why not to have big impacts at a smaller scale too?

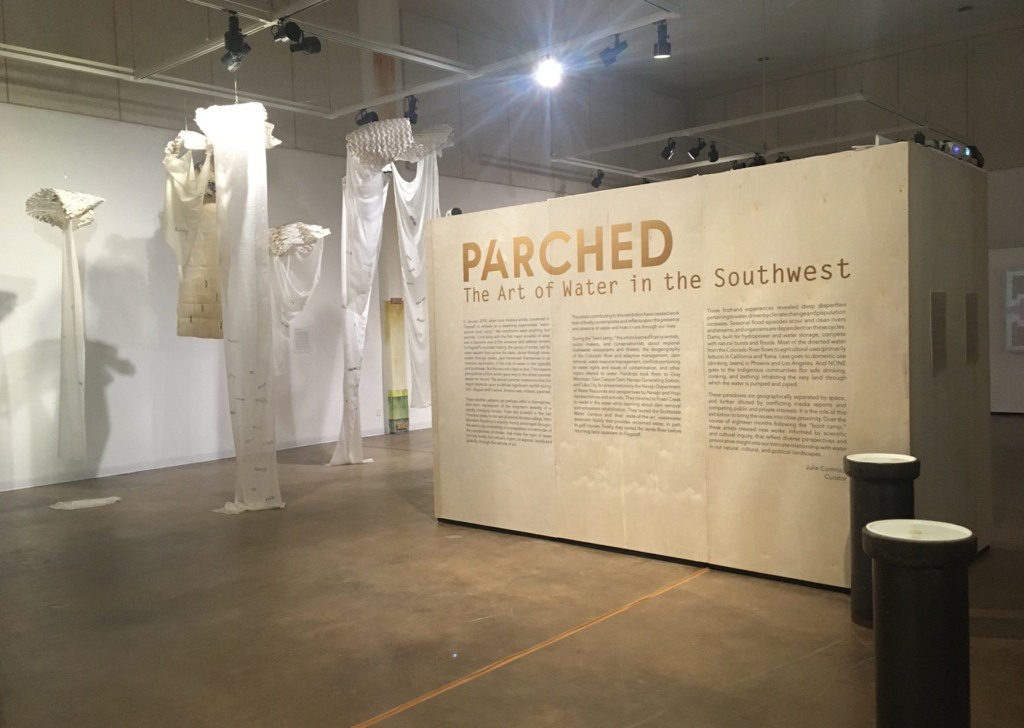

The same thoughts have come to mind as I have spent time exploring the artwork that makes up the Parched: The Art of Water in the Southwest exhibit at the Coconino Center for the Arts here in Flagstaff. Full disclosure: I wrote the text for the catalog, which is also mounted in shorter form on the gallery walls. The exhibit’s nine artists all live in Arizona, but they come from a wide range of backgrounds and cultural traditions, and they work in a wide range of media, from performance to film to watercolor to photography to on-site installation.

What links them? Well, a focus on the scarcity or value of water, for one. There’s very little actual water in the gallery space or in the films projected there. Instead, there’s the sense that water speaks so very loudly in this part of the world precisely because it’s not common. Because it’s the limiting factor in what happens—whether in terms of what nature does or of what human societies are able to do. In this region how we understand and use water embodies the connection between humans and the rest of the living, breathing world—both good and bad.

If you’re in or near Flagstaff it’s worth reserving a viewing time (it’s free, and the gallery allows plenty of space for social distancing) so that you can see how Glory Tacheenie-Campoy’s diaphanous fabric clouds hang down, lightly embossed with Native names for water, as if those multitudinous voices were trying to whisper the moisture down to the ground. You can see how Kathleen Velo managed to have water from different places register photographs of itself, and how watercolorist Debra Edgerton explored the microscopic world of freshwater algae. Installation artist Shawn Skabelund and dancer Delisa Myles teamed up to create an allegory about drought and change. Neal Galloway contributed a sand sculpture and a hard-hitting visualization of inequities in how much water costs for different users. Klee Benally created a pair of remarkable three-dimensional pieces that directly link Navajo reverence for water with multiple layers of political decision-making. Josh Biggs’ aerial photographs document how a desert landscape’s colors speak eloquently about water. And a film by Marie Gladue, who lives on Black Mesa, plumbs what people can do with spirit and body to connect with water.

Whether or not you are able to get to the gallery, you can also attend a virtual panel featuring the exhibit curator, Julie Comnick, and three other panelists who will be exploring the complex nature of viewpoints on water in the region. It takes place Thursday, November 12, at 5 PM (MST), and requires free registration.

The prevailing wisdom about water stories in the Southwest is dire: in the short term, a La Niña winter may mean dry conditions; in the long term, climate change almost certainly means higher temperatures and altered precipitation patterns. And the prognosis about our shared polity is also mixed at best. But certainly we can all hope that inflection points are real—and commit to doing the hard work to ensure they really point to a new direction.