By the time this article posts, I will know whether or not I have cancer.

By the time this article posts, I will know whether or not I have cancer.

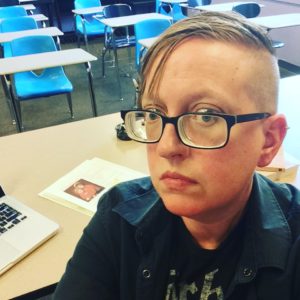

I enjoy teaching my students about writing hooks. Sometimes, albeit rarely, the moment you’re living in provides the best possible hook. I’ve also told students who wish to write, “Start with where you are right now.”

So for this piece, I’m starting where I am right now: waiting.

When I was in my 20s, a former professor-turned-mentor-turned-friend gave me a set of mala beads and taught me my first mantra: “What’s this? Don’t know.” I’ve used both the beads and the mantra for almost two decades: before flights, before first dates, dental work—basically before anything that’s rendered me uneasy.

Last week, I used the beads and mantra ahead of a biopsy.

The last biopsy I had was in 2011. That one turned out to be cancer that required surgery, 12 rounds of chemo and 30 days of radiation. I no longer have the luxury of presuming strange bumps are nothing.

My second and most recent biopsy took place on my fifth wedding anniversary. My wife snuck away from work to sit beside me and do what I could not: watch the ultrasound monitor, watch the radiologist guide the long needles into the mass on my chest wall. Numbed with Lidocaine and curled on my left side, I caught my wife’s brown eyes, asked about her co-workers whose children I teach: “What’s so-and-so’s kid up to over break?” This was less about sincere curiosity and more about a need to transport myself elsewhere, to find an escape hatch, a place I could drop into that wasn’t this small room where a kindly man, younger than me, was trying to pierce my back.

“What’s this? Don’t know.” The point is that all I know—all any of us know—is the moment in which we are dwelling. Easy enough, if not for the fact that the mind is always jetting off elsewhere, toggling between the past and attempting to predict the future. If I am honest, in this moment, about the things I know for certain, the results are trivial, often obscure, oddly specific: I know dogs only poop north-south facing. I know that, for a little while, Virginia and Leonard Woolf owned a pet monkey. I know Manhattans and champagne do not pair well, and that Andy Warhol died during gallbladder surgery. I know that Needles, California, is the first stop for the Joads in Grapes of Wrath and that the same town is named after mountain ranges that look more like teeth than needles, but nevertheless believe “Teeth, California” would be a friendlier name for a town than “Needles.”

At the dawn of the new decade, I practice patience. Uncertainty renders me acutely aware of where I derive joy: watering and spritzing my kitchen plants—a decrepit fern, two robust succulents, two spider plants—a happy string of pearls, wrapping my hands around a mug of warm coffee, the sweetness of our dog when he’s napping, his chin turning silver, how gorgeous my wife is when she’s reading a book, her eyes widening, lips bending. I absorb the easy laugh of my colleague Mike, and savor the incisive, albeit playful, insults from my friend Virgil. I notice the smell of woodsmoke and delight in three hours spent at a coffee house with my friend Stacy discussing everything from medical procedures to the literary scene (which are not so different, after all). I remember this acute awareness of joy from years ago, when I absolutely had cancer, and I remember the May morning I awoke, chemo bald, to robins chirping and said aloud, “Shut up, you stupid birds.” (I’ve omitted the expletives.)

Lust for life never lasts, at least not in my case. When what we fear becomes as ordinary as folding sheets (as cancer did in my 30s), we can’t necessarily sustain what Philip Lopate called the “spectacle of joie de vivre.” So as I wait, I am enjoying these moments of myopic delight.

I tell my students never to write about that on which they lack perspective. “The situation must be six months or older,” I tell them. And here I am breaking my own cardinal rule. I have no perspective on this situation. “What’s this? Don’t know.”

When I came home from my biopsy, I made a cup of Earl Grey, redonned my pajamas and slipped on my headphones, going directly to Aretha Franklin’s “Won’t Be Long”—a lusty song about a lovers’ reunion, but a song whose beat and refrain resonated with me as I sat with the waiting I’d have to do for the next three to five business days, like waiting on a UPS delivery that is your entire mortal existence.

Though I am a teacher and therefore perhaps more well versed in patience than some, I hate waiting. I am fond of that which is early, on time, prompt: the student who is seated before the bell, the flight that takes off on schedule, the swiftly returned call. Waiting leaves me with too many blanks to fill, and my imagination can be cruel.

But there is no cure for a wait, certainly not those like this. There simply is no antidote; one wears the waiting like a yoke and goes on with the music, the conversation, the books, the writing, the guilty indulgences (mine, as of late, has been video games), the hot coffee, the classroom, the laughter, the beads, the moment.