My initial exposure to America’s great national parks came as a perk with my first magazine subscription. Thanks to an inspired second-grade teacher who worked to instill a love of nature in her students, I became an avid reader of Ranger Rick magazine. As a subscription bonus I received a set of national parks color-by-number drawings, to be completed not with paint but with a set of colored pencils, easier for children to manage.

My initial exposure to America’s great national parks came as a perk with my first magazine subscription. Thanks to an inspired second-grade teacher who worked to instill a love of nature in her students, I became an avid reader of Ranger Rick magazine. As a subscription bonus I received a set of national parks color-by-number drawings, to be completed not with paint but with a set of colored pencils, easier for children to manage.

The national parks in this depiction were of course idyllic: towering trees to be completed in forest green, light green and at least two shades of brown; deeply incised canyons with their palette of burnt orange, sunshine yellow and peach; and rustic lodges of timber and heavy stone (light gray). I’m pretty sure at least some of the panels featured friendly park rangers (light flesh-colored) in their flat-topped gray hats. More than Mr. Rogers or Bozo the Clown, and almost as much as the striving roster of the early ‘70s Cubs, these simple, almost abstract portraits became my role models. It was a way of life that with its curious squirrels, sky-blue jaybirds, majestic elk and pristine landscapes blended with respectful visitors seemed infinitely more appealing than the monotonous Chicago suburbs. Even though I’d hardly been to any national parks at all, in my heart I felt I knew where to find my place.

But this is not to say that my path to these places was in any way smooth or predictable, for soon there were other draws on my attention—big cities, loud music and my belief that if I was going to be an urbane writer then it was a given that I had to be urban as well. It wasn’t until much later, in my late 20s, that I realized my affinities were pulling me toward exactly what had appealed to me so strongly in second grade: grand landscapes, open spaces, interesting wildlife and the sense that there still existed places whose ultimate purpose was something larger than serving as a handy place to put more houses or roads or malls. Once I moved out west I came to think of the national parks as a sort of archipelago of hospitable places in which I could find not only grandeur but also like-minded fellow travelers with a shared sense of space and quiet and gut-level enjoyment of being a body at work in a challenging landscape.

Now it’s almost Earth Day, which, since my Ranger Rick days, has morphed from what in retrospect seems a fairly simply cry for clean water and air to a much more primal—and unfortunately politically more challenging—expression that the planet simply ought to remain livable for future generations. And so the parks seem more imperiled and more critical than ever. They’re threatened not only by the short-sighted resource rapacity of extractive industries and their chums in politics (see: Bear’s Ears, Grand Staircase-Escalante), but by climate change, which may before too long have consequences like seeing most of the saguaros die out of Saguaro National Park as the Southwest grows ever hotter.

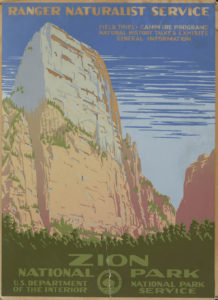

In other ways, too, the parks remind us that this new era that many have come to call the Anthropocene is all about humans simply coming to dominate more and more places to an ever greater degree. That was pretty apparent this past weekend, when on a camping trip I felt it was time to have my 13-year-old son experience the giddy excitement of hiking up to Angels Landing in Zion. It’s a vertiginous trail, if you haven’t been there, on which you navigate a narrow ridge and shimmy up slickrock channels high above sheer drops, often steadying yourself by grabbing onto chains mounted on the rocks, all the while either enjoying or trying to ignore (depending on your disposition) the views of Zion Canyon more than a thousand feet below. It’s spectacular—and these days, on a pleasant spring weekend—very, very crowded. Sometimes alarmingly so, as queues of visitors wanting up or down form long groups whose safety is contingent on everyone remaining both patient and sure-footed.

In those conditions it’s easy to reach the conclusion that the popular parks have become too hopelessly crowded, that they no longer provide the very values they were set up to provide, namely the sense of the sublime that comes of feeling that humans are only a very tiny part of the landscape. It’s even easy to get a nagging, unkind feeling—especially as a sometimes entitled-feeling resident of what is in many ways a national park entry community—that the swarms of visitors are a threat on par with the developers and the politicians and climate change itself.

But they’re not. In our age of technology addiction and media saturation we should celebrate that so many people want to experience the outdoors, even if some of them may be looking forward to their Instagram fix as much as to the experience itself.

And we should be grateful, and watchful, too, for the other virtues of the parks. For despite the crowding of certain places the parks still offer what I glimpsed dimly, in a limited palette of colors, all those years ago. We learned that the day after our Angels Landing hike, when we hiked somewhere else—I won’t tell you where—where we were able to slink barefoot up onto slickrock and find an intimate spot with budding spring trees and singing canyon tree frogs. There were still grand canyon walls way off in the distance, but this was a different experience of nature, one that we shared with only two other hikers who happened by. It was multicolored, multisensory.

It was good to know that people had the foresight, generations ago, to establish that not only Angels Landing but also numerous hidden nooks like this ought to be protected for good, ought to be kept available for all of us. That’s the kind of foresight for future generations that we all could use some more of these days.