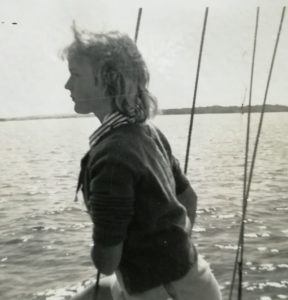

The women in my family were sailors, the men fly fishermen. From fathers and grandfathers we learned the dubious art of exaggeration—“It was this long! No kidding! A shame it got away!”—useful for future con men and writers. From the women we learned the practical skills of navigation, patience and how to predict the weather. We learned to plot a course, to use a sextant, to read the stars, to read a compass—a necessary skill in the foggy Maine summers. We learned how to put together an extraordinary lunch while close-hauled and heeling, and we learned to respect the toughness of canvas as we mended a torn sail after a storm.

My mother was already a seasoned sailor when she met my father, and though he never succeeded in lighting a fly fishing fire under her, she quickly passed on to him a love of the sea. Every summer of my childhood and prickly adolescence, my family would spend two weeks—my father’s entire vacation—on a forty-foot schooner out of Northeast Harbor, Maine. Her name was Niliraga. (Back then all boats were referred to in the feminine.) At the time she belonged to my mother’s mother, Florence Montgomery. I’ve only recently learned niliraga is a Sanskrit word meaning “constant in affection,” and the story of her name wraps around the story of her first owner, my grandmother’s stepfather, a man named Gano Dunn.

Apparently Gano Dunn, prior to Niliraga’s construction, spent a summer on Sutton Island off the coast of Maine. His neighbor that summer happened to be a Harvard linguist with a specialty in Sanskrit. I imagine them out in a field overlooking the sea, dressed in white linen trousers and Oxford shirts, straw hats on their heads and open jackets flapping in the wind off the Western Way. They’ve perambulated the island, picked a few handfuls of blueberries, soaked their sturdy walking shoes in a bog and ducked their heads under spruce limbs. Now they’ve come to sit on two large boulders below Mr. Dunn’s rented cottage. They get to talking about his longing for a sailboat, his dream of a floating summer home. The linguist privately reflects that his friend Mr. Dunn, a widower, most certainly longs for the wife he has lost. In his own mind, never having married or desired to, a ship would do just as well. He encourages the enterprise and comes up with the perfect name for a faithful companion: Niliraga.

My step great-grandfather did in fact spend every summer after that living aboard the schooner Niliraga. The story goes that he’d pass the day sailing, in fair weather or foul, and in the evening take up the oars of his dory and row ashore. He’d walk up to my Great Aunt Agnes’s house in time for dinner, and after a few enjoyable hours of conversation and an after-dinner brandy he’d return to the Niliraga and sleep like a baby.

Gano Dunn is only one of the eccentrics in my family but his story is among the most eyebrow-raising. It’s said that he courted my grandmother Florence and her two sisters, Agnes and Mary, and in the end married their newly divorced mother, my great-grandmother Julie. He was an electrical engineer who, as a young man, was offered a job by Thomas Edison and worked with Nikola Tesla. My father claimed to have had his first experience of television at Mr. Dunn’s home while courting my mother who lived with Gano while going to college. The television was a rectangular box you looked down into and there in the darkness you could make out a moving image, usually a cowboy on a galloping horse.

The Niliraga was a 1928 Alden schooner, a wooden boat with a utilitarian girth yet handsome under sail. She slept six and a cat comfortably, with plenty of room to move about the cabin and deck room enough to keep us out of each other’s hair. She had a comfortable bowsprit (the place at the front or bow of a boat where a figurehead might go), and that’s where I took myself when I needed to remember who I was. Every sense organ came alive on that schooner. She creaked and groaned under sail or at anchor. The taste of salt was everywhere and the sharp, fishy, vegetable smell of the sea. I loved the feel of rope in my hands, the halyards that raised the sails and the sheets that trimmed them. Our horizon was endless on clear days but in the ubiquitous Maine fog we traveled blind and only found our bearings by the moan of fog horns and the clang of bell buoys which appeared ghostly out of what seemed like a limitless rushing obscurity, then disappeared.

At eleven o’clock in the morning my father passed around Hershey bars and at four in the afternoon, even in a high sea, my mother went below and worked magic on the gimbaled stove, producing tea and Pepperidge Farm cookies. Is it too much to say a sailboat taught me how to be in a family as much as a family taught me to sail? There was so much darn togetherness and so much cooperation needed to respond to the shifting winds that sailed us. She had no winches, no gadgets. It took a crew of us to raise her sails, haul them in, pull up the anchor. Charts and a good set of eyes were the only navigational systems we had. We got on each other’s nerves and fought and played a lot of Scrabble and Go Fish and ate candy bars and ran each other’s underwear up the mast in an ongoing, tiresome joke we never tired of. We grew up and my parents, who inherited the Niliraga, needed a younger, easier vessel, and sold her.

When my mother died we asked my father’s brother Shep to make a box for her ashes. Shep is a fly fisherman and a sailor, a blend of what used to be two distinct bloodlines in our family. He knew my mother well and knew exactly where to find the wood for her box. He learned that Niliraga now resided in Bangor, Maine, along the Penobscot River. He saw it fitting that the old schooner would once again enclose my mother, that they would remain constant in one another’s affection. He found her, or what remained of her: a rotting pile of timbers under a bridge but with one mysteriously untouched length of teak, a piece of her deck no doubt. He brought it home.